Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (12 page)

Bancroft led National League shortstops in fielding twice. He also finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting twice, even though the award was not presented in any of the 1915-1923 seasons.

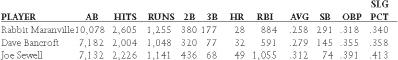

Bancroft was a good player. The problem is, he probably wasn’t quite good enough, nor did he accomplish enough during his career to justify his induction into the Hall of Fame. Playing mostly in a hitter’s era, Bancroft finished his career with a .279 batting average. He also compiled only 591 runs batted in and 1,048 runs scored in just over 7,000 career at-bats (roughly, the equivalent of 14 full seasons). That averages out to approximately 42 RBIs and 75 runs scored a year, hardly Hall of Fame numbers, even for a shortstop. Let’s look at his numbers next to those of Rabbit Maranville and Joe Sewell, both of whom were also excellent fielders:

Bancroft’s numbers clearly come up far short of the figures compiled by the other two men in virtually every category. Maranville’s statistical superiority is largely the result of his greater longevity. Sewell was simply a much better hitter than Bancroft. However, regardless of the reason, it becomes apparent that, in spite of his strong defense, Bancroft’s statistics should not have been good enough to get him into the Hall of Fame.

Hughie Jennings

There are two things that prevent Hughie Jennings from being a legitimate Hall of Famer. The first is that he didn’t play long enough, or have enough plate appearances, to be considered a valid choice. The second is that the only good offensive seasons he had were from 1894 to 1900, when batting averages throughout all of baseball were extremely high. In the previous three seasons, and in Jennings’ last three years, he did virtually nothing on offense.

From 1891 to 1893, Jennings posted batting averages of .292, .224 and .181. Then, in 1894, a year in which the league average rose to over .300, Jennings batted .335. Over the next three seasons, he hit .386, .401 and .355—impressive numbers in any era. He also knocked in over 100 runs, and scored 100 more in each of those seasons. After two more good years in which he batted over .300 and scored 100 runs, the rules changes that went into effect at the turn of the century brought Jennings’ numbers back down to earth, and he never again hit over .300.

Jennings ended his career after the 1903 season with less than 5,000 at-bats, not even the equivalent of ten full seasons. He was a full-time player for only seven seasons. While both his career batting average of .311 and his lifetime on-base percentage of .390 are fairly impressive, Jennings finished with only 840 RBIs, 994 runs scored, and 18 home runs. In addition, he never led his league in any offensive category and was just a mediocre fielder. Even with fielding averages being much lower at that time than they would become in later years, Jennings’ career mark of .922 was below the league average of about .935 to .940.

Bobby Wallace

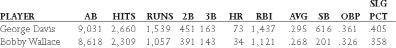

The Veterans Committee elected Bobby Wallace to the Hall of Fame in 1953, 45 years before George Davis was elected. Looking at their numbers, it is hard to figure out why:

Playing in essentially the same time period, in almost the same number of at-bats, Davis finished well ahead of Wallace in every offensive category. In particular, note the discrepancy in runs scored, runs batted in, stolen bases, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage. In addition, while Davis batted over .300 nine times, scored 100 runs five times, and led the league in runs batted in once, Wallace batted over .300 just twice, never scored 100 runs in a season, and never led the league in any offensive category. While Wallace did lead the league in fielding twice, Davis finished at the top of the league rankings four times.

In short, Bobby Wallace was a good player. But, when his numbers are compared to those of a legitimate Hall of Famer like George Davis, it becomes apparent that he does not belong in Cooperstown.

Phil Rizzuto

The evaluation of the Hall of Fame credentials of this particular player is extremely difficult for me due to personal reasons. Having grown up in the Bronx as a huge Yankees fan during the 1960s and 1970s,

The Scooter

holds a special place in my heart. Although his last season as a player was 1956, the year I was born, I grew up watching him on television and listening to his voice on the radio as an announcer for the team. Rizzuto had such an endearing quality to him that it was impossible, even if you were a Yankee hater, to dislike him. He was funny, entertaining, natural, and, perhaps more than anything else, unpretentious. This ability to be himself, and to laugh at himself, was probably the quality that people most appreciated about him. When Phil passed away in 2007, millions of Yankee fans, myself included, felt as if they lost a member of their own family. Feeling as I do about

The Scooter

is what makes saying this so hard, but, looking at things completely objectively, Phil Rizzuto should not be in the Hall of Fame.

That last statement should not be misinterpreted to mean that Rizzuto was not a fine player, or that he was one of the worst players elected to Cooperstown. He was a fine player, and there are several players in the Hall of Fame who are less deserving than Phil. However, Rizzuto’s resume is just not impressive enough to allow him to be classified as a legitimate Hall of Famer. Let’s take a look.

In a 13-year career, Rizzuto batted .273, drove in 563 runs, scored another 877, totaled 1,588 hits, and hit 38 home runs. He batted over .300 twice, scored more than 100 runs twice, and led American League shortstops in fielding twice. He was selected to the All-Star Team five times and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player in 1950. That season was Rizzuto’s finest, as he established career-highs in virtually every offensive category by batting .324, scoring 125 runs, totaling 200 hits, hitting seven homers, and rapping out 36 doubles. He also finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting on two other occasions, finishing second to Ted Williams a year earlier.

However, let’s take a hard look at the numbers: Aside from his two .300 seasons, Rizzuto batted as high as .270 only five other times, never hitting any higher than .284 in any other season. Not always a leadoff hitter, he never drove in more than 68 runs in any season, and, with the exception of his two 100-plus seasons, scored as many as 80 runs only two other times. Aside from his 200-hit season in 1950, Rizzuto never had more than 169 hits in any other year. Although he was said to have been the American League’s most feared baserunner of his era, Rizzuto never stole more than 22 bases in a season, never led the league in that department, and stole only 149 bags in his career. While it is true that Rizzuto played during an era in which stealing bases was not heavily emphasized—especially by the Yankee teams on which he played—he was obviously not his league’s version of Lou Brock, Maury Wills, or even Jackie Robinson.

It was also said that Rizzuto did the little things to help his team win; things like bunting, hitting behind the runner, and playing good defense. While this is certainly true, the little things can only do so much. A Hall of Famer needs to do much more, and Rizzuto’s career totals indicate that he just did not do enough.

Others argue that he played on winning teams and was a major contributor to their success. While it is true that the Yankees won ten pennants and eight world championships during his career, and that Rizzuto was a major contributor, it is also true that they did just as well before he arrived, and just as well after he left. Rizzuto’s first season was 1941, and his last was 1956. From 1936 to 1940, New York won four pennants and four world championships. From 1957 to 1964, they won seven pennants and three world championships. Therefore, how much of a factor in the team’s success could Rizzuto have been? More likely, it was DiMaggio, Berra, Mantle, and Ford who had a greater impact.

In actuality, the arguments about Rizzuto doing the little things to help his team win, and being a major contributor to a winning team’s success could just as easily be applied to Bert Campaneris. While Rizzuto was slightly better defensively, and was also a somewhat better all-around player, due to longevity, Campaneris posted superior career numbers in most categories. Campy was also a far better base-stealer. In addition, Campaneris, like Rizzuto, was an excellent bunter, and he played on five division-winning and three world championship teams in Oakland. Former A’s owner Charlie Finley once said that Campaneris was the most valuable player on his Oakland teams during the championship years. Yet Campaneris has drawn virtually no support for induction into Cooperstown.

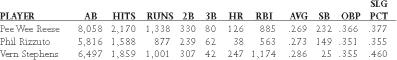

One other argument that has been waged on Rizzuto’s behalf is that he was extremely comparable to Pee Wee Reese, who was elected to the Hall of Fame ten years earlier. While it is true that both men played shortstop in the city of New York, for winning teams at the same time, a closer look at the two men reveals that they were not truly comparable as players. Using just our Hall of Fame criteria, Rizzuto was a five-time All-Star; Reese was selected to the All-Star Team ten times. Rizzuto finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting three times, winning the award once; while Reese never won the award, he did finish in the top 10 eight times. While Reese was the best shortstop in the N.L from 1946 to 1953, Rizzuto was the best in the A.L. only in 1950 and, perhaps, in 1951 as well. A look at their career numbers, along with those of Vern Stephens, who played the same position for the St. Louis Browns and Boston Red Sox at the same time, reveals the overall disparity:

Reese finished well ahead of Rizzuto in virtually every offensive category, and was a comparable defensive player. Stephens, who is not in the Hall of Fame, not only finished well ahead of Rizzuto in most categories, but also had better overall numbers than Reese. While he was not as good defensively as either Reese or Rizzuto, Stephens was far from a liability in the field. He wasn’t as quick as the other two men, but he had a powerful throwing arm that allowed him to accumulate more assists annually. Probably more than with his defense, however, Stephens suffers in comparison to Reese and Rizzuto in other areas. He was not as much of a team leader as either Reese or Rizzuto, and the teams he played for were not as successful as either the Dodgers or the Yankees. Furthermore, the general consensus was that Stephens did not do as many little things to help his team win.

While all of the above may be true, there are certain perceptions that were held towards Stephens that are not totally accurate. Rizzuto and Reese were viewed as being winning ballplayers who were extremely cerebral in their approach to the game. Meanwhile, Stephens was seen as being a somewhat one-dimensional player who did not know how to win. After all, he played for some Boston Red Sox teams in the late ’40s and early ’50s that were thought to be even more talented than the Yankee teams that repeatedly edged them out in the pennant race. The general perception was that those Red Sox teams didn’t have the pitching or defense that those Yankee teams had (which was probably true), that they didn’t do the little things, such as bunting and hitting behind runners, that a winning team does (which may have been true), and that Stephens was one of the primary culprits (which may or may not have been true). It was also thought that Stephens benefited greatly from playing in Fenway Park. While it is true that, as a righthanded power-hitter, he was aided somewhat playing his home games there, it is also true that Stephens put up better numbers on the road alone than many shortstops accumulated over the entire season.