Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (4 page)

The numbers would seem to indicate that, with the exception of home runs, both Cepeda and Perez were very comparable players to McCovey. The latter had a couple of truly dominant seasons that separated him somewhat from Cepeda and Perez. He also won a Most Valuable Player Award, something Cepeda accomplished as well, but Perez failed to do. However, both Cepeda and Perez were actually a bit more consistent than McCovey, and had more quality seasons over the course of their respective careers.

A look at the career of McCovey reveals that he had only seven truly outstanding seasons; those in which he hit over 30 home runs and drove in close to, or more than, 100 runs. As was mentioned earlier, he was selected to the N.L. All-Star team six times. Cepeda, however, actually had nine

All-Star type

seasons, even though he was selected to the team only seven times. In nine different seasons, he hit close to, or more than, 30 home runs, drove in approximately 100 runs, and batted over .300. Perez was perhaps the most consistent RBI-man in the game from 1967 to 1977. In each of those 11 seasons he knocked in more than 90 runs while hitting more than 20 homers and batting above .280 on most occasions. Perez was also selected to the All-Star team seven times.

Let’s take a look at how both Cepeda and Perez stack up when evaluating their careers based on the selection criteria we are using to define a Hall of Famer:

Neither Cepeda nor Perez was ever the best player in the game at any point during his career. Nor was either man among the five or six best players in baseball for an extended period of time, or one of the greatest first basemen in the history of the game. However, it could be argued that each man was the top player at his position for an extended period of time. From 1959 to 1962, then again in 1967, Cepeda was arguably the best first baseman in baseball. From 1959 to 1962, he averaged 33 home runs and 114 runs batted in, while batting near or above .300 each season. In 1961, he led the N.L. with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs, while batting .311 for the San Francisco Giants. In 1967, he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player when he helped lead the St. Louis Cardinals to the pennant and world championship by hitting 25 homers, leading the league with 111 runs batted in, and batting .325.

Perez vied with Ron Santo of the Cubs for the honor of being the best National League third baseman from 1967 to 1970. After being shifted to first base at the conclusion of the 1971 campaign, he was the league’s top first baseman in both 1972 and 1973.

In the MVP voting, both players received a reasonable amount of support. As we saw earlier, Cepeda won the award in 1967. He also finished second once (in 1961), and in the top 10 one other time. Perez finished in the top 10 in the balloting four times. Both players were selected to the All-Star team seven times. Cepeda was a league-leader in a major statistical category only three times, topping the N.L. in home runs once, and in runs batted in twice. Despite knocking in more than 100 runs seven times, Perez never led the league in any offensive category.

Neither player was particularly strong defensively, but it would appear that Perez had some intangible qualities that Cepeda may have lacked. In 1961, when Cepeda led the National League in home runs and runs batted in, Giants manager Alvin Dark was quoted as saying, “I’m sick and tired of players on this team leading the league in home runs and RBIs and not doing anything to help us win!” It is true that Dark’s opinion of Cepeda may have been somewhat jaded since, later in his managerial career, he was quoted as having made some racist remarks. Nevertheless, the big first baseman—at least in Dark’s eyes—did not do the little things to help his team win. Perez, on the other hand, was a great team leader who helped lead the Cincinnati Reds to four pennants and two world championships. His manager with the Reds, Sparky Anderson, once said that all the other leaders on the Big Red Machine (i.e. Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan and Pete Rose) deferred to

the Big Dawg,

as Perez was known to his teammates. He was the leader on that team.

In evaluating the credentials of Cepeda and Perez, we discover that we have two very good players who meet about half of our Hall of Fame criteria. The feeling here is that both men should be viewed as borderline candidates who were not the greatest of choices, but who were far from the worst. They were both much better players than many of the other men who have been elected to Cooperstown.

Frank Chance/George Kelly

This brings us to the final two first basemen in the Hall of Fame: Frank Chance and George “High-Pockets” Kelly.

Frank Chance played first base for the Chicago Cubs from 1898 to 1914. He also managed the team for several of those seasons. Chance was fortunate enough to have played on the great Cubs teams that dominated the National League for much of the first decade of the 20th century. Playing mostly during the dead-ball era, one would not expect Chance’s offensive numbers to be on a par with some of the other great first basemen who have been elected to Cooperstown. However, one would have to look long and hard to be able to justify his selection.

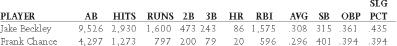

During Chance’s career, he led the National League in stolen bases and on-base percentage twice each, and in runs scored once. However, he was never a league-leader in any other offensive category. A look at the statistics compiled by Chance over the course of his 17 major league seasons indicates that he neither had a sufficient number of plate appearances nor the necessary numbers to be deemed a worthy Hall of Famer. Let’s take a look at his numbers alongside those of Jake Beckley, whose career overlapped with Chance’s:

Certainly, a large part of the discrepancy in the numbers posted by the two men can be attributed to the fact that Beckley had more than twice as many plate appearances as Chance. However, Beckly was also the far more productive hitter of the two. He had a huge edge over Chance in every statistical category except stolen bases and on-base percentage. Beckley, already described here as a somewhat marginal Hall of Famer, had three times as many triples, more than four times as many homers, and almost three times as many runs batted in as Chance. Regardless of the era in which he played, 20 career home runs, 596 runs batted in, and 797 runs scored should not be enough to get a player elected into the Hall of Fame.

The only reasonable explanation as to why Chance was elected comes from a poem that was written by a New York sportswriter during the first decade of the 20th century. Frustrated that his beloved Giants were repeatedly victimized by the powerful Cubs teams of those years, this writer composed a poem extolling the virtues of Chicago’s double-play combination of shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers, and first baseman Chance. The poem became quite famous and ended up immortalizing the trio, and the phrase “Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance.” As a result, the three men were elected

en masse

to the Hall of Fame by the Old-Timers Committee in 1946, in one of the many blunders it committed during this period. None of the three players truly deserved to be admitted to Cooperstown.

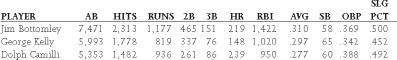

George Kelly was the regular first baseman for the New York Giants for much of the 1920s, prior to being displaced by Bill Terry. During his career, he surpassed the 100-RBI mark five times and led the N.L. in home runs once and in runs batted in twice. He never led the league in any other offensive category, and he never scored as many 100 runs in a season. Let’s take a look at his numbers alongside those of Jim Bottomley, who we have categorized as a legitimate Hall of Famer, and Dolph Camilli, the slugging first baseman for the Phillies and Dodgers from 1933 to 1945, who never made it into the Hall:

Clearly, Kelly’s numbers fall far short of those compiled by Bottomley, who played during the same period. Meanwhile, Camilli, playing in an era less dominated by hitting, posted numbers that compare quite favorably to Kelly’s. In approximately 600 fewer at-bats than Kelly, he hit almost 100 more home runs, knocked in only 70 fewer runs, accumulated more triples, scored more runs, and posted much higher on-base and slugging percentages. The logical question then is this: Why is Kelly in the Hall of Fame while Camilli is not? The answer is a simple one: Frankie Frisch. As we saw earlier, Frisch’s strong personality and leadership skills enabled him to exert a great deal of influence over the other members in his years on the Veterans Committee. He argued extensively for his former Giants and Cardinals teammates, and was successful in getting many of them elected. However, Kelly, while a very solid player, really did not deserve to be inducted into the Hall of Fame any more than Camilli, Hal Trosky, Ted Kluszewski, Gil Hodges, Steve Garvey, Don Mattingly, Keith Hernandez, or about a half dozen other first basemen.

Speaking of Hodges, over the years there has been much clamoring for his election to the Hall of Fame. His supporters point to his 370 home runs, 1,274 runs batted in, six seasons with more than 30 homers, two 40-homer campaigns, seven seasons with more than 100 RBIs, eight All-Star game appearances, and integral role on those great Dodger teams of the 1950s, and wonder why he has yet to be elected. The fact is, while Hodges was a fine player and a good man, he simply does not deserve to be enshrined into Cooperstown.

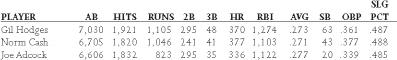

Hodges never led the league in any major offensive category. In spite of the fact that the Dodger teams for which he played were always in contention, winning six pennants in his years with the team, he never finished any higher than eighth in the league MVP voting, placing in the top 10 only three times. While Hodges had seasons in which he was the National League’s top first baseman, he was not generally regarded as the league’s dominant player at his position during his era (Ted Kluszewski, Joe Adcock, and, later, after he was shifted from leftfield, Stan Musial were all perceived as being on his level). More importantly, Hodges was generally considered to be only the fifth, or sixth, best player on his own team, behind Roy Campanella, Duke Snider, Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, and, perhaps, Don Newcombe. A look at Hodges’ career numbers, compared to two other first basemen not in the Hall of Fame, seems to support the theory that he wasn’t quite good enough to be included among the game’s elite:

Joe Adcock was a contemporary of Hodges who spent most of his career with the Milwaukee Braves. Although Hodges’ numbers were slightly better, the two players were actually quite comparable. Yet there has been virtually no support for Adcock’s election to the Hall of Fame.

The same could be said for Norm Cash, who played for the Detroit Tigers during the 1960s and early 1970s, in much more of a pitcher’s era than when Hodges played. In slightly fewer at-bats, Cash put up virtually the same numbers as Hodges. While it could be said that Tiger Stadium was a great ballpark for hitters, the same was true of Ebbetts Field, Hodges’ home ballpark.