Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (14 page)

When the first set of Hall of Fame elections was held in 1936, the two players who received the most support from the original Veterans Committee were Cap Anson and Buck Ewing. After subsequent tallies were taken over the next three years, both men were enshrined in Cooperstown when the Hall first opened in 1939. The results of that balloting are a clear indication of the respect that Buck Ewing garnered from baseball people of the day.

In fact, not only was Ewing considered to be unquestionably the greatest catcher to play in the major leagues prior to Mickey Cochrane and Bill Dickey, but he was thought to be one of the very best players of the 19th century. He was clearly one of the most versatile. In just under 5,400 career at-bats, Ewing batted .303, knocked in 883 runs, scored 1,129 others, amassed 178 triples, and stole 354 bases. In a career spanning parts of 18 seasons, he batted over .300 eleven times, knocked in over 100 runs once, scored more than 100 runs once, and reached double-digits in triples eleven times, once totaling as many as 20. He led the league in home runs and triples once each, and had his finest season in 1893. That year, Ewing knocked in 122 runs, batted .344, scored 117 runs, accumulated 15 triples, and stole 47 bases—one of four times during his career that he finished with at least 40 steals. While many players from that era struggled with their batting averages prior to the rules changes that went into effect in 1893, Ewing batted over .300 in every season from 1885 to 1892. He was probably, along with Dan Brouthers, Cap Anson, Billy Hamilton, Sam Thompson, and Ed Delahanty, one of the six best position players of the 19th century.

James Raleigh “Biz” Mackey

Since he was generally considered to be the second greatest catcher in Negro League history, behind only Josh Gibson, it would seem that Biz Mackey’s 2006 Hall of Fame induction was long overdue. Mackey spent the better part of three decades playing for nine different teams in the Negro Leagues. Although he originally came up as a shortstop, Mackey became the regular catcher for the Philadelphia Hilldales in 1925 and subsequently developed into what most Negro League experts considered to be the greatest defensive catcher in the history of black baseball. Possessing a powerful and accurate throwing arm, Mackey typically gunned down opposing baserunners with throws made from a squatting position. A tremendous all-around receiver, Mackey was a studious observer of opposing batters and an expert handler of pitchers. He was also extremely agile behind the plate, despite his lack of running speed.

More than just an outstanding defensive player, the switch-hitting Mackey was also a good hitter, with power from both sides of the plate. He placed among the Negro Leagues’ all-time leaders in total bases, RBIs, and slugging percentage, while hitting either .322 or .335 for his career, depending on the source. Mackey won two Negro League batting titles, hitting .423 for the Hilldales in 1923, and topping the circuit once more in 1931 with a mark of .359. He also compiled a batting average of .358 against major league competition in exhibition games.

Still, it was largely Mackey’s defense on which he built his reputation, and that established him, in the minds of some, as the greatest catcher in Negro League history. Indeed, Homestead Grays manager Cum Posey rated him as his number-one all-time catcher, placing him ahead of Josh Gibson. Posey is on record as having stated, “Mackey was a tremendous hitter, a fierce competitor, although slow afoot he is the standout among catchers who have shown their wares in this nation.”

In 1937, while serving as player/manager for the Baltimore Elite Giants, Mackey began mentoring the 15-year-old Roy Campanella in the fine points of catching. Campanella later recalled:

“In my opinion, Biz Mackey was the master of defense of all catchers. When I was a kid in Philadelphia, I saw both Mackey and Mickey Cochrane in their primes, but, for real catching skills, I don’t think Cochrane was the master of defense that Mackey was. When I went under his direction in Baltimore, I was 15 years old. I gathered quite a bit from Mackey, watching how he did things, how he blocked low pitches, how he shifted his feet for an outside pitch, how he threw with a short, quick, accurate throw without drawing back. I got all this from Mackey at a young age.”

Louis Santop

Another outstanding former Negro League catcher whose longtime exclusion from the Hall of Fame seems rather dubious was Louis Santop. Referred to as “The Black Babe Ruth” long before anyone ever heard of Josh Gibson, Santop was black baseball’s greatest slugger of the Deadball Era.

The six-foot four-inch, 240-pound Santop played for several teams during a 17-year career that began in 1910 with the Lincoln Giants. While with the Giants, Santop caught two of the greatest pitchers in Negro League history, Smokey Joe Williams and Cannonball Dick Redding. Considered to be an above-average defensive catcher, Santop had a powerful throwing arm that intimidated opposing baserunners.

But, it was Santop’s hitting that truly frightened opposing teams. The lefthanded power hitter was known for his tape measure home runs, and for occasionally calling his shots before he hit them. Once, in 1912, he hit a ball that was said to have traveled 500 feet—particularly amazing when it is considered that the blow was struck against a Deadball Era baseball. Santop was more than just a slugger, though. While the integrity of the data surrounding his career statistics is somewhat questionable, records indicate that Santop frequently posted batting averages in excess of .400 during his 17 seasons in the Negro Leagues.

Carlton Fisk

Most people would probably say that Carlton Fisk being in the Hall of Fame should be a no-brainer. After all, prior to being surpassed in home runs by Mike Piazza, he held the record for most career home runs by a catcher (350), most stolen bases, and most games caught. He is also one of only three catchers, along with Johnny Bench and Yogi Berra, to hit 300 home runs, score 1,000 runs, and drive in 1,000 runs. The feeling here, though, is that Fisk’s credentials need to be examined more closely since most of the numbers he compiled during his career were based more on longevity than on greatness.

Carlton Fisk was a regular catcher in the big leagues, first for the Boston Red Sox and, later, for the Chicago White Sox, from 1972 to 1991. One of the reasons why Fisk lasted as long as he did was that he never pushed himself to the limit, and played through injuries, the way some of his contemporaries such as Johnny Bench and Thurman Munson did. In those 20 seasons, Fisk had as many as 500 official at-bats only four times, and as many as 400 at-bats in only nine other seasons. As a basis for comparison, in his 16 seasons as a regular, Bench had at least 500 at-bats eight times, and surpassed 600 plate appearances twice; in his 10 seasons as a regular, Munson surpassed 500 at-bats seven times, and had more than 600 plate appearances on two occasions.

Nevertheless, over his 25-year major league career, Fisk was able to hit 376 home runs, drive in 1,330 runs, score 1,276 others, and steal 128 bases—all fairly impressive numbers. He hit more than 20 homers eight times, topping the 30-mark once, knocked in more than 100 runs twice, batted over .300 twice, and scored more than 100 runs once. He was also a fine defensive catcher who had a reputation for being a good handler of pitchers.

But, how does Fisk rate in terms of the Hall of Fame criteria being used here? While he was never considered to be either the best player in baseball or the best player in his league, with the possible exception of Josh Gibson and Johnny Bench, neither were any of the other catchers elected to Cooperstown. Therefore, those factors cannot be held against him. The same can be said for his not being among the five or six best players in the game at any time. However, due largely to his tremendous longevity, a valid case could be made for Fisk being one of the ten best catchers in baseball history.

Was he, for an extended period of time, considered to be the best player in the game, or in his league, at his position? Well, with the possible exception of the 1977 season, it could not be said that he was ever thought of as being the best catcher in baseball. Playing for the Red Sox that year, Fisk had his finest season by hitting 26 home runs, driving in 102 runs, and batting .315. Yet Johnny Bench’s numbers were just as impressive (31, 109, .275). Throughout the rest of his career, Fisk was rated behind either Bench, Munson, Ted Simmons, or Gary Carter. In the American League, Fisk was the top catcher in 1972 (22 HR, 61 RBIs, .293 AVG), 1977 (26 HR, 102 RBIs, .315 AVG), 1978 (20 HR, 88 RBIs, .284 AVG), 1983 (26 HR, 86 RBIs, .289 AVG), and 1985 (37 HR, 107 RBIs, .238 AVG).

In the MVP voting, Fisk finished in the top 10 four times, placing as high as third in 1983. He was also selected to the All-Star Team 11 times.

Fisk never led the league in any major offensive category, but he finished second in both home runs and runs scored once. He was also a team leader and a major contributor to his team’s success.

Thus, overall, it could be said that Fisk does moderately well when using our Hall of Fame selection criteria as a benchmark. However, there were two other catchers whose careers overlapped with Fisk’s who were comparable to him as players, yet who have not been elected to the Hall of Fame.

Those catchers were Joe Torre and Ted Simmons. Simmons has received virtually no support, and it has become rather apparent that, if Torre is ever going to be elected, it will have to be largely on the strength of the success he had managing the Yankees. Torre’s career totals don’t quite measure up to the numbers compiled by Fisk. But it was Fisk’s greater longevity, not his superiority as a player, that is responsible for the statistical edge he holds over Torre. The latter hit more than 20 homers six times, knocked in more than 100 runs five times, batted over .300 four times, was selected to the All-Star Team nine times (six times as a catcher), and won a Most Valuable Player Award. And, despite Fisk’s decided advantage in home runs, stolen bases, and runs scored, Simmons compares quite favorably to Fisk in most offensive categories. Indeed, Simmons may well have been a better all-around hitter than Fisk.

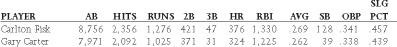

Let’s take a look at the career statistics of all three players:

In addition, Simmons hit more than 20 homers six times, knocked in over 100 runs three times, batted over .300 seven times, was selected to the All-Star Team eight times, and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting three times.

Torre was considered to be the best catcher in baseball from 1964 to 1967, in addition to his MVP season of 1971, which was as a third baseman. Simmons was ranked behind Bench for most of his career, but was actually the superior player in at least two or three seasons.

This should not be misinterpreted to suggest that Torre and Simmons should be elected to the Hall of Fame as well; there have already been too many borderline players voted in. Rather, the suggestion here is that Fisk’s election should not have been viewed as having been such an obvious one. Due to the numbers he accumulated over the course of his career, he probably does deserve a place in Cooperstown. However, he should be thought of more as a borderline Hall of Famer than as a clear-cut choice. And, if he made it in so easily, both Simmons and Torre should have received far more support.

Gary Carter

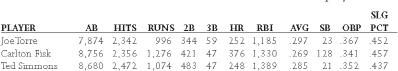

While Carlton Fisk was elected to the Hall of Fame in just his second year of eligibility, it took Gary Carter six tries to make it into Cooperstown. This is somewhat surprising because, while Fisk’s career numbers are slightly more impressive, Carter was actually a very similar player, and was thought of just as highly throughout most of his career.

Like Fisk, Carter had very good power, hitting more than 20 homers nine times during his career, and topping the 30-mark twice. He knocked in more than 100 runs four times, twice as many times as Fisk, and even led his league in that department once, something Fisk never did. Carter was the best catcher in baseball from 1980 to 1986, and was arguably one of the five best players in the game in at least two of those seasons. In 1984, as a member of the Montreal Expos, he hit 27 home runs, led the National League with 106 runs batted in, and batted .294. The following season, playing for the Mets, he hit 32 homers, drove in 100 runs, and batted .281.

A look at the career numbers of Fisk and Carter indicates just how similar they really were as players: