B0041VYHGW EBOK (170 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Tokyo Story

’s narration is, by classical standards, rather oblique. Sometimes we learn of important narrative events only after they have occurred. The last portion of

Tokyo Story,

for example, involves a series of events surrounding the sudden illness and death of the grandmother of the family. Although the grandparents are the film’s two central characters, we do not see the grandmother falling ill. We hear about it only when her son and daughter receive telegrams with the news. Similarly, the grandmother’s death occurs between scenes. In one scene, her children are gathered by her bedside; in the next scene, they are mourning her.

Yet these ellipses are not evidence of a fast-paced film such as

His Girl Friday,

which must cover a lot of narrative ground in a hurry. On the contrary, the sequences of

Tokyo Story

often linger over details: the melancholy conversation between the grandfather and his friends in a bar as they discuss their disappointment in their children or the grandmother’s walk on a Sunday with her grandchild. The result is a shift in the narrative balance. Key narrative events are deemphasized by means of ellipses, whereas narrative events that we do see in the plot are simple and understated.

Accompanying this shift away from a presentation of the most highly dramatic events of the narrative is a sliding away from narratively significant space. Scenes do not begin and end with shots that frame the most important narrative elements in the mise-en-scene. Instead of the usual transitional devices, such as dissolves and fades, Ozu typically employs a series of separate transitional shots linked by cuts. And these transitional shots often show spaces not directly connected with the action of the scene; the spaces are usually

near

where that action will take place. The opening of the film, for example, has five shots of the port town of Onomichi—the bay, schoolchildren, a passing train—before the sixth shot reveals the grandparents packing for their trip to Tokyo. Although a couple of important motifs make their first appearances in these first five shots, no narrative causes occur to get the action underway. (Compare the openings of

His Girl Friday

and

North by Northwest.

) Nor do these transitional shots appear only at the beginning. Several sequences in Tokyo start with shots of factory smokestacks, even though no action ever occurs in these locales.

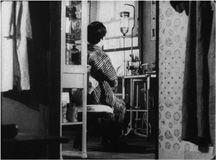

These transitions have only a minimal function as establishing shots. Sometimes the transitions don’t establish space at all but tend to confuse the space of the upcoming scene. After the daughter-in-law, Noriko, gets a phone call at work telling her of the grandmother’s illness, the scene ends in a medium shot of her sitting pensively at her desk; the only diegetic sound is the loud clack of typewriters

(

11.43

).

A nondiegetic musical transition comes up in this shot. Then there is a cut to a low-angle long shot of a building under construction

(

11.44

).

Riveting noises replace the typewriters, with the music continuing. The next shot is another low angle of the construction site

(

11.45

).

11.43 In

Tokyo Story,

a shot of Noriko at her desk …

11.44 … leads to a shot of a building …

11.45 … and then another of construction …

A cut changes the locale to the clinic belonging to the eldest son, Dr. Hirayama. The sister, Shige, is present. The music ends and the new scene begins

(

11.46

).

In this segment, the two shots of the construction site are not necessary to the action. The film does not give us any indication of where the building under construction is. We might assume that it is outside Noriko’s office, but the riveting sound is not audible in the interior shots.

11.46 … before shifting to the locale for the next scene.

“I don’t think the film has a grammar. I don’t think film has but one form. If a good film results, then that film has created its own grammar.”

— Yasujiro Ozu, director

As usual, we should look for the functions of such stylistic devices. It is hard to assign such transitional shots either explicit or implicit meanings. For example, someone might propose that the transitional shots symbolize the new Tokyo that is alien to the visiting grandparents from a village reminiscent of the old Japan. But often the transitional spaces do not involve outdoor locales, and some shots are within the characters’ homes. A more systematic function, we suggest, is narrational, having to do with the flow of story information.

Ozu’s narration alternates between scenes of story action and inserted portions that lead us to or away from them. As we watch the film, we start to form expectations about these wedged-in shots. Ozu emphasizes stylistic patterning by creating anticipation about when a transition will come and what it will show. The patterning may delay our expectations and even create some surprise.

For example, early in the film, Mrs. Hirayama, the doctor’s wife, argues with her son, Minoru, over where to move his desk to make room for the grandparents. This issue is dropped, and there follows a scene of the grandparents’ arrival. This ends on a conversation in an upstairs room. Transitional music again comes up over the end of the scene. The next shot frames an empty hallway downstairs that contains Minoru’s school desk, but no one is in the shot. There follows an exterior long shot of children running along a ridge near the house; these children are not characters in the action. Finally, a cut back inside reveals Minoru at his father’s desk in the clinic portion of the house, studying. Here the editing creates a very indirect route between two scenes, going first to a place where we expect a character to be (at his own desk) but is not; then the scene moves completely away from the action, outdoors. Only then, in the third shot, does a character reappear and the action continue. In these transitional passages, a kind of game emerges, one that asks us to form expectations not only about story action but about the editing and mise-en-scene.

Within scenes, Ozu’s editing patterns are as systematic as those of Hollywood, but they tend to be sharply opposed to continuity rules. For example, Ozu does not observe the 180° line, the axis of action. Nor is his violation of these rules occasional, as John Ford’s is in

Stagecoach

(

p. 244

). Ozu frequently cuts 180° across the line to frame the scene’s space from the opposite direction. This, of course, violates rules of screen direction, since characters or objects on the right in the first shot will appear on the left in the second, and vice versa. At the beginning of a scene in Shige’s beauty salon, the initial interior medium shot frames Shige from opposite the front door

(

11.47

).

Then a 180° cut reveals a medium long shot of a woman under a hair dryer; the camera now faces the rear of the salon

(

11.48

).

Another 180° cut presents a new long shot of the room, again oriented toward the door, and the grandparents come into the salon

(

11.49

).

Rather than being an isolated violation of continuity rules, this is Ozu’s typical way of framing and editing a scene.

11.47 In the beauty salon, systematic cutting moves from one side of the axis of action …

11.48 … to the other side …

11.49 … and back again.