B0041VYHGW EBOK (168 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

11.30 … give glimpses of Michel’s actions …

11.31 … in pointing a gun …

11.32 … and the death of the cop, without showing anything clearly.

In contrast to the whirlwind presentation of this key action, a lengthy conversation in the middle of the film brings the narrative progression almost to a standstill. For nearly 25 minutes, Michel and Patricia chat in her bedroom. At some points, Michel attempts to further his goals, trying vainly to phone Antonio and to persuade Patricia to come to Rome. Most of the conversation, however, is trivial, as when Michel criticizes the way Patricia puts on lipstick or when she asks whether he prefers records or the radio. The pair try to outstare each other, and they discuss Patricia’s new poster. So rambling is their exchange that some critics have assumed that the dialogue was improvised (although Godard attests that it was all scripted).

At one point, Patricia suggests that she will not run off with him because she does not know if she loves him. Michel: “When will you know?” Patricia: “Soon.” Michel: “What does that mean—soon? In a month, in a year?” Patricia: “Soon means soon.” So although the pair make love, by the end of the long scene (which occupies nearly a third of this 89-minute film), we still do not have a definite step forward or backward in Michel’s courting of Patricia, and he has made no progress toward escaping. Such scenes make him seem more like a wandering, easily distracted delinquent than the desperate, driven hero of a film noir.

It is not until the scene outside the

Tribune

office that another decisive causal action occurs. A passerby (played by Godard) recognizes Michel from a newspaper photograph and tells the police. This triggers a chain of events that will lead to Michel’s death. Yet now the plot meanders once more. In the next scene, Patricia participates in a news conference with a famous novelist, a character unrelated to the main action. Most of the questions asked by the reporters deal with the differences between men and women, but the novelist’s responses seem more playful than meaningful. Finally, Patricia asks him his greatest ambition, and he replies enigmatically, “To become immortal and then to die.” Patricia’s puzzled glance into the camera that ends the scene hints at the ambiguity that will linger at the film’s end.

After Detective Vital questions Patricia at the

Tribune

office, she and Michel realize that the police are on his trail. Now

Breathless

begins to progress in a somewhat more conventional way. In the next scene, Patricia says that she loves Michel “enormously,” and they steal a car. Here Michel seems to reach his romantic goal, as Patricia commits herself to fleeing with him. When Antonio agrees to bring the cash the next morning, Michel moves toward his second goal. We might anticipate possible outcomes: the pair will escape, or one or both will be killed in the attempt. The next morning, however, Patricia confounds our expectations by betraying Michel to Vital. Even then Michel has a last chance. Antonio arrives just before the police, with money and a getaway car—yet Michel cannot bring himself to leave Patricia.

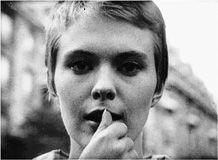

The ending is particularly enigmatic. As Michel lies bleeding to death, Patricia looks down at him. He slowly makes the same playful faces at her that he had made during their bedroom conversation. Muttering, “That’s really disgusting” (“C’est vraiment dégueulasse”), he dies. Patricia asks Detective Vital what he said, and Vital misreports Michel’s last words: “He said, ‘You are really a bitch’” (“Il a dit, ‘Vous êtes vraiment une dégueulasse’”). We are left to ponder what Michel thought was disgusting—Patricia’s betrayal, his own last-minute failure to flee, or simply his death. In the final shot, Patricia looks out at the camera, asks what “dégueulasse” means, rubs her lips with the Bogart-inspired gesture that Michel has used throughout the film

(

11.33

),

and abruptly turns her back on us as the image fades out.

11.33 Patricia’s enigmatic gesture at the end of

Breathless.

Breathless

achieves a degree of closure: Michel fails to achieve his goals. But we are left with many questions. Although Michel and Patricia talk constantly about themselves, we learn remarkably little about why they act as they do. Unlike characters in classical films, they do not have a set of clearly defined traits. The film begins with Michel saying, “All in all, I’m a dumb bastard,” and in a way, his actions bear this out. Yet we never learn background information that would explain his decisions. Why did he become a car thief? Since he casually leaves his female accomplice early in the film, what makes him willing to risk death to stay with Patricia, a woman whom he has known only briefly? Because dying for the love of an unworthy woman is what a would-be Hollywood hero is supposed to do?

Patricia’s traits and goals are even more amorphous and ambiguous. When Michel first finds her selling newspapers on the Champs Elysées, she is far from welcoming. Yet at the scene’s end, she runs back to give him a kiss. She keeps saying she wants to get a job as a

Tribune

reporter and to write a novel, yet she seems to throw these ambitions away when she thinks she loves Michel. Patricia also tells Michel she is pregnant by him, but she has not received the final test results, and she never raises this as a reason she should stay in Paris. She often says that she is scared, yet after she and Michel steal a car, she remarks, “It’s too late now to be scared.” This hints that she has resolved her own doubts and has thrown in her lot with Michel. When she suddenly betrays him, she does not intend that he should be killed but simply wants to force him to leave her. Still, her speech about why she informed on Michel seems not really to explain her abrupt change of heart. Just as Michel is ill-suited to be a tough guy, Patricia is too naive and indecisive to play the role of the classic femme fatale.

In the outlaw film noir, the characters are intensely committed to each other; here Michel and Patricia seem to have few strong feelings about what they do. When the treacherous woman deceives the noir hero, he often becomes bitterly disillusioned; but Michel apparently does not blame Patricia for betraying him. It is as if these ambivalent, diffident, confused characters are unable to play out the desperately passionate roles that the Hollywood tradition has assigned to them.

Breathless

’s elliptical, occasionally opaque, narrative is presented through techniques that are equally unconventional. As we have seen, Hollywood films use a three-point system of key light, fill light, and backlight, carefully controlled in a film studio (

pp. 128

–

129

).

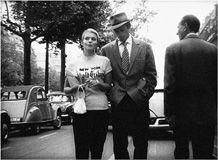

Breathless

was shot entirely on location, even for interiors. Godard and cinematographer Raoul Coutard opted not to add any artificial light in the settings. As a result, the characters’ faces sometimes fall into shadow

(

11.34

).

11.34 When Patricia sits against a window and lights a cigarette, the natural light of the scene illuminates her only from behind.

Filming on location, especially in small apartments, would ordinarily make it difficult to obtain a variety of camera angles and movements. But taking advantage of new portable equipment, Coutard was able to film while hand-holding the camera. Several lengthy tracking shots follow the characters

(

11.35

).

Coutard apparently sat in a wheelchair to film this shot, as well as more elaborate movements that follow the characters in interiors

(

11.36

).

Such shots recall the location shooting of many films noirs, such as the final airport scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s

The Killing,

but the low camera position and the passersby who turn to look at the actors (as with the man at the right in

11.35

) call attention to the technique in a way that departs from Hollywood usage.

11.35 Michel’s first meeting with Patricia as she strolls along the Champs Elysées selling papers occurs in a threeminute take.