B0041VYHGW EBOK (169 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

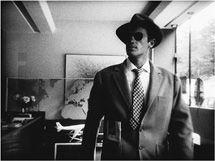

11.36 When Michel visits a travel agent trying to claim his check, the framing glides and turns with ease as he moves around the desks and through the corridors.

Even more striking than the mise-en-scene is Godard’s editing. Again he sometimes follows tradition, but at other points, he breaks away. Standard shot/reverseshot cutting organizes several scenes

(

11.37

,

11.38

).

Similarly, when Michel spots the man examining the telltale photo in the newspaper, Godard supplies correctly matched glances. Since this is a turning point in the plot, the adherence to the 180° rule makes it evident that the man has spotted Michel and may inform on him.

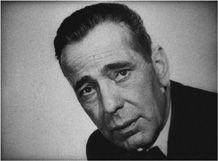

11.37 When Michel pauses in front of a movie theater and looks at a photo on display …

11.38 … Bogart seems to look back at him in reverse shot.

Yet what makes the film still quite jolting today are its violations of continuity editing. In Hollywood films made before the 1960s, the jump cut, in which a segment of time is eliminated without the camera being moved to a new vantage point (

pp. 254

–257), was deplored. Yet

Breathless

employs jump cuts throughout. In an early scene, when Michel visits an old girlfriend, jump cuts shift their positions abruptly

(

11.39

,

11.40

).

We have seen another example, when Godard presents a series of jump cuts of Patricia during a conversation in a car (

6.137

,

6.138

, again showing the last and first frames of contiguous shots).

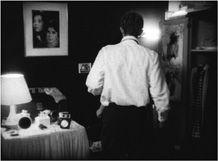

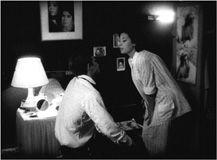

11.39 The last frame of one shot during Michel’s visit to an old girlfriend …

11.40 … and the first of the next shot, creating a jump cut.

Even when Godard shifts the camera position between cuts, he may drop out a bit of time or mismatch the actors’ positions. At many cuts, the action seems to jerk forward. One effect of this jumpy editing is to enliven the rhythm. At times, as during the murder of the police officer, we have to be very alert to follow the action. The elliptical editing also makes certain scenes stand out by contrast: the lengthy single-take scenes with moving camera and the rambling 25-minute conversation in Patricia’s apartment.

“On

À Bout de souffle,

he’d [Godard] ask the script-girl what kind of shot was required next to fulfill the requirements of traditional continuity. She’d tell him, and then he’d do the exact opposite.”— Raoul Coutard, cinematographer

Aside from avoiding matches on action, Godard often flaunts the moments when he does not adhere to the 180° rule, as when Patricia walks along reading a paper

(

11.41

,

11.42

).

In the opening scene, as Michel’s accomplice points out a car he wants to steal, the eyelines are quite unclear, and we get little sense of where the two are in relation to each other.

11.41 In the first shot, Patricia moves from left to right …

11.42 … and in the next, she is walking right to left, a flagrant violation of conventional screen direction.

The film’s sound often reinforces these editing discontinuities. When the characters’ dialogue and other diegetic sounds continue over the jump cuts, we are forced to notice the contradiction: time is apparently omitted from the visual track but not from the sound track. The location shooting also created situations in which ambient noises intrude on the dialogue. A passing siren outside Patricia’s apartment nearly overwhelms her conversation with Michel during the long central scene. Later the press conference with Parvulesco inexplicably takes place on an airport observation platform, where the loud whines of nearby planes drown out conversation. Such scenes lack the balance of volumes of the well-mixed Hollywood sound track.

Godard’s avoidance of the rules of smooth sound and picture steers

Breathless

away from the glamorous portrayals seen in the Hollywood crime film. The stylistic awkwardness suits the pseudo-documentary roughness of filming in an actual, hectic Paris. The discontinuities are also consistent with other nontraditional techniques, like the motif of the characters’ mysterious glances into the camera. In addition, the jolts in picture and sound create a self-conscious narration that makes the viewer aware of its stylistic choices. In making the director’s hand more apparent, the film presents itself as a deliberately unpolished revision of tradition.

Godard did not set out to criticize Hollywood films. Instead, he took genre conventions identified with 1940s America and gave them a contemporary Parisian setting and a modern, self-conscious treatment. He thereby created a new type of hero and heroine. Aimless, somewhat banal, lovers on the run became central to later outlaw movies such as

Bonnie and Clyde, Badlands,

and

True Romance.

More broadly, Godard’s film became a model for directors who wished to create exuberantly offhand homages to, and reworkings of, Hollywood tradition. This attitude would be central to the stylistic movement that

Breathless

helped launch, the French New Wave. (See

Chapter 12

,

pp. 475

–477.)

1953. Shochiku/Ofuna, Japan. Directed by Yasujiro Ozu. Script by Ozu and Kogo Noda. Photographed by Yuharu Atsuta. With Chishu Ryu, Chieko Higashiyama, So Yamamura, Haruko Sugimura, Setsuko Hara.

We have seen how the classical Hollywood approach to filmmaking created a stylistic system (continuity) in order to establish and maintain a clear narrative space and time. The continuity system is a specific set of guidelines that a filmmaker may follow. But some filmmakers do not use the continuity system. They may flaunt the guidelines by violating them, as Godard does in

Breathless,

creating a casual yet lively film. Or they may develop a set of alternative guidelines—at least as strict as Hollywood’s—that allows them to make films that are quite distinct from classical films.

Yasujiro Ozu is one such filmmaker. His approach to the creation of a narrative differs from that used in more classical films like

His Girl Friday

or

North by Northwest.

Instead of making narrative events the central organizing principle, Ozu tends to decenter narrative somewhat. As a result, spatial and temporal structures come forward and create their own interest.

Tokyo Story,

the first Ozu film to make a considerable impression in the West, offers an enlightening introduction to some of Ozu’s characteristic filmmaking strategies.

Tokyo Story

presents a simple narrative of an elderly provincial couple who visit their grown children in Tokyo, only to find themselves treated as inconvenient nuisances. The narrative is quiet and contemplative, yet Ozu’s style does not simply conform to some characteristically spiritual Japanese system of filmmaking. Indeed, Japanese filmmakers and critics found his nonclassical approach as puzzling as did Western audiences. By creating a systematic alternative method of shaping spatial and temporal relations, Ozu sought to engage the spectator’s attention more deeply. In Hollywood, style is subservient to narrative, but Ozu makes it an equal partner. We watch the narrative action, the spatial relations, and the temporal relations unfold simultaneously, and all are equally dramatic and engaging. As a result, even a simple narrative like that of

Tokyo Story

becomes fresh and fascinating.