B0041VYHGW EBOK (113 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Most films create the impression that the people and things onscreen simply produce an appropriate noise. But, as we saw in

Chapter 1

, in the process of film production, the sound track is constructed separately from the images, and it can be manipulated independently. This makes sound as flexible and wide-ranging as other film techniques.

Yet sound is perhaps the hardest technique to study. We’re accustomed to ignoring many of the sounds in our environment. Our primary information about the layout of our surroundings comes from sight, and so in ordinary life, sound is often simply a background for our visual attention. Similarly, we speak of

watching

a film and of being movie

viewers

or

spectators

—all terms that suggest the sound track is a secondary factor. We’re strongly inclined to think of sound as simply an accompaniment to the real basis of cinema: the moving images.

Moreover, we can’t stop the film and freeze an instant of sound, as we can study a frame to examine mise-en-scene and cinematography. Nor can we lay out the sound track for our inspection as easily as we can examine the editing of a string of shots. In film, the sounds and the patterns they form are elusive. This elusiveness accounts for part of the power of this technique: sound can achieve very strong effects and yet remain quite unnoticeable. To study sound, we must learn to

listen

to films.

Fortunately, filmgoers have become more sensitive.

Star Wars

and other hits of the 1970s introduced the broad public to new technologies of sound recording and reproduction. Audiences came to expect Dolby noise reduction processes, expanded frequency and dynamic range, and four- and six-track theater playback. During the early 1990s, digital sound became routine for big-budget pictures, and now virtually all releases have crisp, dense sound tracks. “An older film like

Casablanca

has an empty soundtrack compared with what we do today,” remarks sound designer Michael Kirchberger, supervising sound editor for

Lost in Translation.

“Tracks are fuller and more of a selling point.” Multiplex theaters upgraded their sound systems to meet the challenge, and the popularity of DVDs prompted consumers to set up home theaters with ravishing sound. Viewers’ new sensitivity to sound is apparent in the recent habit of starting a film’s sound track with dialogue or sound effects, before the images appear. You can argue that this device serves to quiet down the audience so that the imagery gets the proper attention, but often the sonic information is important to the story as well. In any event, not since the first talkies of the late 1920s have filmgoers been so aware of what they hear.

Whether noticed or not, sound is a powerful film technique for several reasons. For one thing, it engages a distinct sense mode. Even before recorded sound was introduced in 1926, silent films were accompanied by orchestra, organ, or piano. At a minimum, the music filled in the silence and gave the spectator a more complete perceptual experience. More significantly, the engagement of hearing opens the possibility of what the Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein called “synchronization of senses”—making a single rhythm or expressive quality unify both image and sound.

The meshing of image and sound appeals to something quite deep in human consciousness. Babies spontaneously connect sounds with what they see. The most basic condition involves timing: if a sound and image occur at the same moment, they are perceived as one event, not two. Just as our minds search for patterns in a shot or for causal patterns in a narrative, we are inclined to seek out patterns that will fuse lip movements and speech, and even musical rhythms with visual ones. Our bias toward audio-visual patterning governs both our everyday activities (imagine hearing a friend’s talk out of synch) and our experiences of arts like music, theater, and film.

“The most exciting moment is the moment when I add the sound…. At this moment, I tremble.”

— Akira Kurosawa, director

Sound is often treated as an accompaniment to the images, but we need to recognize that it can actively shape how we understand them. In one sequence of

Letter from Siberia

(

7.1

–

7.4

),

Chris Marker demonstrates the power of sound to alter our understanding of images. Three times Marker shows the same footage—a shot of a bus passing a car on a city street, three shots of workers paving a street. But each time the footage is accompanied by a completely different sound track. Compare the three versions tabulated alongside the sequence in

Table 7.1

. The first one is heavily affirmative, the second is harshly critical, and the third mixes praise and criticism. The audience will construe the same images differently, depending on the sound track.

TABLE 7.1

Letter From Siberia

Footage

The

Letter from Siberia

sequence demonstrates another advantage of sound: film sound can direct our attention quite specifically within the image. When the commentator describes the “blood-colored buses,” we are likely to look at the bus and not at the car. When Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers are executing an intricate step, chances are that we watch their bodies and not the silent nightclub spectators looking on. In such ways, sound can guide us through the images.

This possibility becomes even more fertile when you consider that the sound cue for some visual element may

anticipate

that element and relay our attention to it. Suppose we have a close-up of a man in a room and hear the creaking of a door opening. If the next shot shows the door, now open, our attention will probably shift to that door, the source of the offscreen sound. But if the second shot shows the door still closed, we will likely ponder our interpretation of the sound. (Maybe it wasn’t a door, after all?) Thus the sound track can clarify image events, contradict them, or render them ambiguous. In all cases, the sound track can enter into an active relation with the image track.

This example of the door opening suggests another advantage of sound. It cues us to form expectations. If we hear a door creaking, we anticipate that someone has entered a room and that we will see the person in the next shot. But if the film draws on conventions of the horror genre, the camera might stay on the man, staring fearfully. We would then be in suspense awaiting the appearance of something frightful off-screen. Horror and mystery films often use the power of sound from an unseen source to engage the audience’s interest, but all types of films can take advantage of this aspect of sound. During the town meeting in

Jaws,

the characters hear a grating sound and turn to look offscreen; a cut reveals Quint’s fingers scraping on a blackboard—creating a dramatic introduction to this character. We’ll see several other cases in which the use of sound can creatively cheat or redirect the viewer’s expectations.

In addition, sound gives a new value to silence. A quiet passage in a film can create almost unbearable tension, forcing the viewer to concentrate on the screen. An abrupt silence can jolt us and arrest our attention

(

7.5

,

7.6

).

Just as color film turns black and white into grades of color, so the use of sound in film will include all the possibilities of silence.

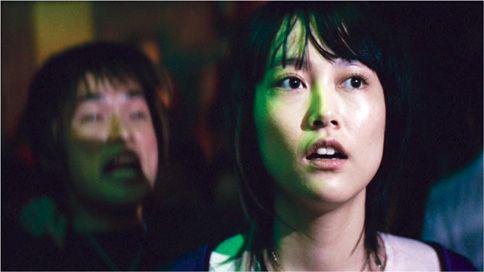

7.5 In

Babel,

when the deaf teenage girl enters the disco, the club music is about to climax.

7.6 Instead, it drops out when we cut to her optical point-of-view on the boy she’s following. Instead of subjective sound, we get subjective silence, and this sharply dramatizes her isolation from what is happening around her.

One more advantage: sound bristles with as many creative possibilities as editing. Through editing, one may join shots of any two spaces to create a meaningful relation. Similarly, the filmmaker can mix any sonic phenomena into a whole. With the introduction of sound cinema, the infinity of visual possibilities was joined by the infinity of acoustic events.

Perceptual Properties

Several aspects of sound as we perceive it are familiar to us from everyday experience and are central to film’s use of sound.

The sound we hear results from vibrations in the air. The amplitude, or breadth, of the vibrations produces our sense of

loudness,

or volume. Film sound constantly manipulates volume. For example, in many films, a long shot of a busy street is accompanied by loud traffic noises, but when two people meet and start to speak, the volume of the traffic drops. Or a dialogue between a soft-spoken character and a blustery one is characterized as much by the difference in volume as by the substance of the talk.

Loudness is also related to perceived distance; often the louder the sound, the closer we take it to be. This sort of assumption seems to be at work in the street traffic example already mentioned: the couple’s dialogue, being louder, is sensed as in the acoustic foreground, while the traffic noise recedes to the background. In addition, a film may startle the viewer by exploiting abrupt and extreme shifts in volume (usually called changes in

dynamics

), as when a quiet scene is interrupted by a very loud noise.

The frequency of sound vibrations affects

pitch,

or the perceived highness or lowness of the sound. Certain instruments, such as the tuning fork, can produce pure tones, but most sounds, in life and on film, are complex tones, batches of different frequencies. Nevertheless, pitch plays a useful role in helping us pick out distinct sounds in a film. It helps us distinguish music and speech from noises. It also serves to distinguish among objects. Thumps can suggest hollow objects, while higher-pitched sounds (like those of jingle bells) suggest smoother or harder surfaces and denser objects.