Another Insane Devotion (30 page)

Read Another Insane Devotion Online

Authors: Peter Trachtenberg

A temporary solution came when she was invited to a residency in Italy. I was happy for her but also envious, and I felt a little peeved at not even getting a proper chance to leave her. I wanted her to pine for me. Instead, shortly after I started teaching, my wife would be flying to Rome, then motoring up north to spend a month being plied with Prosecco, prosciutto, and figs under the cypress trees. I worried that it might make her sad to be so close to where she'd found Gattino. She said it wouldn't: nothing could make her sadder than she already was. She said it defiantly, as if I were the one who'd asked her, “So that's your trauma?” Eight months had passed since our cat had disappeared: she was still wearing the black veil, and she was wearing it over her face.

But who was going to care for the cats? I couldn't take them down to North Carolina with me; my landlords there were allergic, and, anyway, I could think of few things more distressing for a cat than to be driven twelve hours in a crate and then cooped up for a year in a house full of strange, unclawable furniture. I could think of few things more distressing for a person than to be the one who drove three of them. We had to get a cat-sitter, not a once-a-day drop by but someone who'd stay in the house. Bruno was the child of friends, a big, strapping kid, raised on the Lower East Side back when it was a habitation of schizophrenics and junkies. He'd gone to the college next door and was still hanging around the neighborhood the way a lot of its graduates did, knowing that never again would they find a place where they and their ideas were taken so seriously. I flew

back from North Carolina to show him around the house, which he clearly loved and was prepared to spend quality time in. He didn't just come with suitcases but with keyboard instruments and a Mac G4 whose monitor was bigger than our TV set and what appeared to be a month's worth of fancy groceries. He wasn't put off when I told him to be careful sitting down on the pot. But he seemed leery of the cats. When I warned him that they might jump up on the table while he was eating and try to get at his food, his eyes widened in alarm.

back from North Carolina to show him around the house, which he clearly loved and was prepared to spend quality time in. He didn't just come with suitcases but with keyboard instruments and a Mac G4 whose monitor was bigger than our TV set and what appeared to be a month's worth of fancy groceries. He wasn't put off when I told him to be careful sitting down on the pot. But he seemed leery of the cats. When I warned him that they might jump up on the table while he was eating and try to get at his food, his eyes widened in alarm.

“What am I supposed to do then?”

“You pick them up and put them down on the floor.”

“They'll let me pick them up?”

I wanted to ask F. if she thought we were making a mistake, but by the time this conversation took place, she was on her way to Europe. Still, I e-mailed her what I told Bruno, figuring she'd appreciate it:

“I doubt they'll be in a position to stop you.”

Â

Once or twice a week, on a schedule we set up by e-mail, F. and I would Skype each other. In theory, it was more intimate than the phone, more like being together in the same place instead of calling out to each other from across an ocean. But really, it felt more remote. I couldn't walk around the house with the phone pressed to my ear, peeling a cucumber at the sink or portioning cat food into three dishes; I had to sit at my desk, as if I were working. My wife's face smiling uncertainly out of a letterbox on my laptop screen made me think of software. You clicked on the icon, and she came jerkily alive. She was so small, and the room behind her was such a generic

room, veiled in shadow with a European light fixture on the ceiling. I'd ask her what the weather was like there. After a pauseâI doubt I'd ever asked her about the weather the whole time we'd been togetherâshe'd tell me. Then she'd ask me what it was like where I was. This was the future that had been foreseen for us when we were kids, by comic books and science fiction movies with F/X crude as a cardboard robot. We had arrived there, and nobody had told us. I don't remember what we talked about. We weren't nearly as expressive as we were in our e-mails, which were still full of gossip and humor and, sometimes, tenderness. The technology that made us present to each other was too intrusive, the lag between words and the moving lips that uttered them, the way her face kept freezing or shattering into a cascade of pixels. Never had I been so conscious of

seeing

another person. After a while, we just made faces at each other. It was more fun.

room, veiled in shadow with a European light fixture on the ceiling. I'd ask her what the weather was like there. After a pauseâI doubt I'd ever asked her about the weather the whole time we'd been togetherâshe'd tell me. Then she'd ask me what it was like where I was. This was the future that had been foreseen for us when we were kids, by comic books and science fiction movies with F/X crude as a cardboard robot. We had arrived there, and nobody had told us. I don't remember what we talked about. We weren't nearly as expressive as we were in our e-mails, which were still full of gossip and humor and, sometimes, tenderness. The technology that made us present to each other was too intrusive, the lag between words and the moving lips that uttered them, the way her face kept freezing or shattering into a cascade of pixels. Never had I been so conscious of

seeing

another person. After a while, we just made faces at each other. It was more fun.

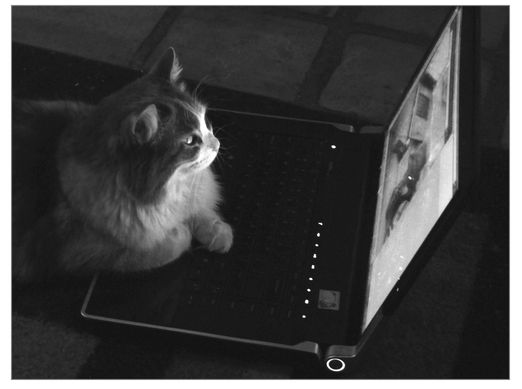

As further evidence of Skype's inadequacy, I was once using it to talk with my twin nieces in Chicago when they asked to see Biscuit. She was right nearby so I lifted her into my lap and held her up to the webcam, and while the girls squealed with pleasure (God knows why, since they had cats of their own, big fat ones twice the size of any of mine), Biscuit was uninterested. She didn't even sniff the screen the way she would a telephone that voices were coming out of. Stoically, she sat on my lap, squirming only a little. It was one more thing I was subjecting her to. You could chalk this up to a cat's poor depth of visual field or to the fact that the squeaking figures on the screen had no smell (only now does it occur to me that on video feed, the girls were about the size of mice). Or you can

ascribe it to an innate refinement of perception that allows a cat to distinguish between a being in the worldâwhat Heidegger calls

Dasein

âand a being reconstituted in cyberspace and to ignore the one in cyberspace, which has nothing nice to give her.

ascribe it to an innate refinement of perception that allows a cat to distinguish between a being in the worldâwhat Heidegger calls

Dasein

âand a being reconstituted in cyberspace and to ignore the one in cyberspace, which has nothing nice to give her.

Maybe what I felt when F. and I Skyped was the anxiety that arises from sensing the disjunction between those beings. Intellectually, yes, I understood that what I was seeing on the screen was in fact F., or the light that had bounced off her in her room in Italy and then been captured by a webcam, digitized, and transmitted over the Internet as packets of data, just as what I was hearing was a digital transcription of her actual voice. I didn't think it was a special effect, though within my lifetime we may reach the point where we can no longer tell an actual person on the screen from a complex animation of that person, maybe stitched together from the billions of digital photo and

video and audio samples that have been taken of her in her lifetime, the ones she posed for, the ones snatched on the sly by surveillance cameras in banks, airports, office buildings, and subway stations, not to mention the cameras that gaze impassively down on our streets, waiting for someone to bite into the vouchsafed fruit and look up with juice shining on her lips.

video and audio samples that have been taken of her in her lifetime, the ones she posed for, the ones snatched on the sly by surveillance cameras in banks, airports, office buildings, and subway stations, not to mention the cameras that gaze impassively down on our streets, waiting for someone to bite into the vouchsafed fruit and look up with juice shining on her lips.

But the F. that I was seeing and talking with was a mediated F., an F. that had been mediated over and over. Between the image on my screen and the woman in a room in Umbria lay an uncounted number of operations, as if a gold coin of great worth had been changed into one currency after another by a series of invisible money changers, one of whom eventually gave me what he said was a sum equivalent to the value of the coin. I guess it was in dollars. But what were the transaction fees? At those moments when F.'s voice didn't sync with the movements of her lips, what was she really saying? When her lively, changeable features were replaced by a Mondrian schematic that might be the universal skeleton of digital beings, what expression was being hidden from me? On seeing her face appear on my screen, I felt the pleasure I always felt on seeing her after some time apart, but how much of that pleasure was borrowed from memory? And if my memory had been as limited or, say, as capricious as Biscuit's, would I have looked at F. with the same incomprehension, seeing only a tiny, smiling figure in a window the size of a credit card, with a piping voice that was almost familiar?

Â

When we speak of love, we must speak not only of desire but delight. Desire doesn't last very longâtypically, no more than

three years. Delight doesn't always last longer than that, but it can. Studies have yet to identify its upward limit. Delight is not a condition of lack but of sufficiency, a plenty wholly independent of the circumstance of possession. You don't have to possess the object of love to delight in it, any more than you have to possess the sun to bake voluptuously in its warmth. You can revel in the object from afar, regardless of whether she loves you back or is even aware of you crouching in your blind, camouflaged in your cloak of reeds. Just watching her is enough. I don't desire Biscuit; I'm relieved to say I never have. But thinking of her, I visualize her busy gait, the purposeful mast of her tail, her trills and chirps of greeting. I recall the way she rubs her jowls against mine, the way she rolls onto her side and pumps her hind legs to tear the guts out of an imaginary enemy, and I'm filled with pleasure. A similar pleasure comes over me when I think of F. Her high, round forehead, which seen in profileâsay, on those afternoons she used to walk down Astor Road beside meâlooks as innocent and intrepid as Mighty Mouse's. Her silent, pop-eyed grimace of mock frustration. The little grunt with which she settles into herself as she gets ready for sleep. Her Midwestern reticence and her heedless blurtings. The look of undisguised appetite she casts at a stranger's entrée in a restaurant, as if at any moment she might reach over and help herself to a forkful of it.

three years. Delight doesn't always last longer than that, but it can. Studies have yet to identify its upward limit. Delight is not a condition of lack but of sufficiency, a plenty wholly independent of the circumstance of possession. You don't have to possess the object of love to delight in it, any more than you have to possess the sun to bake voluptuously in its warmth. You can revel in the object from afar, regardless of whether she loves you back or is even aware of you crouching in your blind, camouflaged in your cloak of reeds. Just watching her is enough. I don't desire Biscuit; I'm relieved to say I never have. But thinking of her, I visualize her busy gait, the purposeful mast of her tail, her trills and chirps of greeting. I recall the way she rubs her jowls against mine, the way she rolls onto her side and pumps her hind legs to tear the guts out of an imaginary enemy, and I'm filled with pleasure. A similar pleasure comes over me when I think of F. Her high, round forehead, which seen in profileâsay, on those afternoons she used to walk down Astor Road beside meâlooks as innocent and intrepid as Mighty Mouse's. Her silent, pop-eyed grimace of mock frustration. The little grunt with which she settles into herself as she gets ready for sleep. Her Midwestern reticence and her heedless blurtings. The look of undisguised appetite she casts at a stranger's entrée in a restaurant, as if at any moment she might reach over and help herself to a forkful of it.

These details seem to reflect something pure and unselfconscious in the object, the object as she is when she thinks no one is looking. When I see my cat or my wife, I seem to be seeing her as she truly is, free of all my wonderful, occluding ideas about her, including (in F.'s case but not Biscuit's) the

wonderful, occluding idea of desire. There's a Zen koan that asks, What was your original face before you were born? Perhaps what I am delighting in are those unborn faces, the woman's, the cat's. And perhaps this pleasure, so generous and self-renewing, allows us to participate, even at a remove, in what God may have felt as he looked down at his creation and became lost in its splendor, maybe to such a degree that for a time he forgot that he created it, that it was his.

wonderful, occluding idea of desire. There's a Zen koan that asks, What was your original face before you were born? Perhaps what I am delighting in are those unborn faces, the woman's, the cat's. And perhaps this pleasure, so generous and self-renewing, allows us to participate, even at a remove, in what God may have felt as he looked down at his creation and became lost in its splendor, maybe to such a degree that for a time he forgot that he created it, that it was his.

In the foregoing, of course, the words “see” and “seeing” are used figuratively as well as literally. It's possible to delight in the love object even when one cannot actually see her, as, for example, when one is separated from the object by time or distance. Under such circumstances, one must be content with the images afforded by other faculties. One must imagine the object as she might be. One must remember her as she was.

Â

Bruno didn't return phone calls with the promptness one values in a cat-sitter. The first week he was at the house, I had to leave four or five messages before he called back to tell meâwearilyâthat the cats were fine. When we Skyped, I told F. I was beginning to think the kid was a lox. As if he'd overheard this and resolved to make a better impression, the next week he called me on a Monday evening, before I'd even begun to pester him. But when his name came up on my caller ID, I felt a twinge of unease, and the moment I heard his voice, my whole being constricted like a single great muscle in spasm.

10

T

HE HOUR PASSED; A DISPATCHER'S VOICE, BLURRED by tiredness and bad acoustics, issued its summons. I made my way to the gate and boarded the late train I had taken so many times with F., the two of us drowsy but excited after a night in the city and eager for bed. The black river scrolled past. The mountains on the other side were invisible now; I could only feel their dreaming weight. The Catskills aren't high as mountains goâgeologically speaking, they aren't even proper mountains but an ancient plateau carved into relief by millions of years of water erosionâbut they're some of the oldest in America. Their original sediments were laid down during the Devonian period, 350 million years ago.

HE HOUR PASSED; A DISPATCHER'S VOICE, BLURRED by tiredness and bad acoustics, issued its summons. I made my way to the gate and boarded the late train I had taken so many times with F., the two of us drowsy but excited after a night in the city and eager for bed. The black river scrolled past. The mountains on the other side were invisible now; I could only feel their dreaming weight. The Catskills aren't high as mountains goâgeologically speaking, they aren't even proper mountains but an ancient plateau carved into relief by millions of years of water erosionâbut they're some of the oldest in America. Their original sediments were laid down during the Devonian period, 350 million years ago.

Washington Irving calls them “fairy mountains,” foreshadowing the enchantment that propels the plot of his most famous story. Rip Van Winkle may be the only character in American literature to have a bridge named after him. The

honor seems all the more anomalous because the story that bears his name is so lightweight. A village loafer, fleeing his scolding wife, wanders into the mountains, where he meets an odd company of men who dress in antiquated clothing and amuse themselves by playing ninepins. They ply Rip with booze till he falls into a drunken sleep. When he awakens, he creeps back home, nervous about what his wife will put him through for having spent the night abroad. Instead, he discovers that twenty years have passed. His wife and most of the people he knew are dead, and the only Rip Van Winkle his neighbors have heard of is his son, who has grown up to be a great idler in his own right. Old Rip is taken in by his daughter and lives to a happy old age. The end. Offhand, that doesn't seem worth a bridge.

honor seems all the more anomalous because the story that bears his name is so lightweight. A village loafer, fleeing his scolding wife, wanders into the mountains, where he meets an odd company of men who dress in antiquated clothing and amuse themselves by playing ninepins. They ply Rip with booze till he falls into a drunken sleep. When he awakens, he creeps back home, nervous about what his wife will put him through for having spent the night abroad. Instead, he discovers that twenty years have passed. His wife and most of the people he knew are dead, and the only Rip Van Winkle his neighbors have heard of is his son, who has grown up to be a great idler in his own right. Old Rip is taken in by his daughter and lives to a happy old age. The end. Offhand, that doesn't seem worth a bridge.

When I got off at my country station, I reflexively looked around for our car. On nights F. came to pick me up, I always loved the moment when I first saw its headlights shine at me across the parking lot and recognized her small face behind the wheel. It wasn't there; I called a taxi. By the time I got to my house, it was one in the morning. I'd been traveling eleven hours and was out more than $500. I stepped through the gate, which creaked, and as if in answer, the light in the bedroom went out, Bruno signaling that he was unavailable for a late-night search party. As transparent as the ruse was, I still kept my voice low. “Biscuit!” I called. “Biscuit!” I could hear the despair in it. What creature in its right mind gravitates to despair? A Saint Bernard, maybe. But not a cat. At last I gave up and went into the barn to sleep. Even with the heater on, it was

cold, and I lay under the thin blanket with my hands clasped between my thighs for warmth.

cold, and I lay under the thin blanket with my hands clasped between my thighs for warmth.

Other books

Age of Consent by Marti Leimbach

The Turncoats (The Thirteenth Series #2) by G.L. Twynham

The Harmony Silk Factory by Tash Aw

Genesis: A Soul Savers Novella by Cook, Kristie

Texas Proud (Vincente 2) by Constance O'Banyon

Fugitive by Phillip Margolin

In the Dead of Night by Aiden James

Where There's a Will by Bailey Bradford

Alphas of Black Fortune Complete Series by Scarlett Rhone

Violent Streets by Don Pendleton