Another Insane Devotion (27 page)

Read Another Insane Devotion Online

Authors: Peter Trachtenberg

Â

In

Modern Painters,

the critic John Ruskin identifies three ranks of perception:

Modern Painters,

the critic John Ruskin identifies three ranks of perception:

The man who perceives rightly, because he does not feel, and to whom the primrose is very accurately the primrose, because he does not love it. Then, secondly, the man who perceives wrongly, because he feels, and to whom the primrose is anything else than a primrose: a star, or a sun, or a fairy's shield, or a forsaken maiden. And then, lastly,

there is the man who perceives rightly in spite of his feelings, and to whom the primrose is for ever nothing else than itselfâa little flower apprehended in the very plain and leafy fact of it, whatever and how many soever the associations and passions may be that crowd around it.

there is the man who perceives rightly in spite of his feelings, and to whom the primrose is for ever nothing else than itselfâa little flower apprehended in the very plain and leafy fact of it, whatever and how many soever the associations and passions may be that crowd around it.

I'm not that familiar with Ruskin's work, but his categories seem sensible to me. This is not an adjective I'd associate with him, given the vinous extravagance of his prose and the weirdness of his personal life. In 1848, at the relatively advanced age of twenty-nine, Ruskin married Effie Gray. She was nineteen. Both of them were virgins.

He had been infatuated with her since meeting her two years before. The letters he wrote her during that time throb with longing, but also with what is pretty clearly sexual dread:

You are like a sweet forest of pleasant glades and whispering branchesâwhere people wander on and on in its playing shadows they know not how farâand when they come near the centre of it, it is all cold and impenetrable. . . . You are like the brightâsoftâswellingâlovely fields of a high glacier covered with fresh morning snowâwhich is lovely to the eyeâand soft and winning on the footâbut beneath, there are winding clefts and dark places in its coldâcold iceâwhere men fall and rise not again.

Following the wedding ceremony at the home of the bride's parents, the couple traveled by carriage to Blair Atholl in the Scottish highlands, where they were to spend the night.

What happened in the bedroom was later recorded by Ruskin's lawyer, who made notes of what his client told him when he was contesting the annulment of his marriage. John and Effie changed into their nightclothes. He lifted her dress from her shoulders. He looked at her. Then he lowered her garment, and after a chaste embrace, they went to bed and slept uneventfully through the night. So they would sleep for the rest of their married life. He told her that he was against having children, who would interfere with his work and make it impossible for her to keep him company when he traveled abroad. There is no evidence as to whether Effie proposed another method of birth control, or knew of one. When she protested that chastity was unnatural, John reminded her that the saints had been celibate. And so she acquiesced, and the Ruskins' marriage remained unconsummated until 1854, when she left him and filed for annulment, provoking a scandal almost as great as those that accompanied the later breakups of Prince Charles and Diana Spencer or John and Elizabeth Edwards. A significant difference was that public outrage fell on the reluctantâI suppose now you would say “withholding”âhusband who had refused to give the wife her debitum. According to the notes taken by Ruskin's lawyer, John told him that when he removed Effie's dress, he was disappointed. Her body was not what he had imagined women's bodies as being like. It was, he said, “not formed to excite passion.” In a letter to her parents, Effie put it less circumspectly: “The reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person.”

This is not at odds with Ruskin's prior experience of female bodies, which was probably limited to the idealized forms of

classical statuary, or to the fact that at the age of forty he would fall in love with a ten-year-old girl.

classical statuary, or to the fact that at the age of forty he would fall in love with a ten-year-old girl.

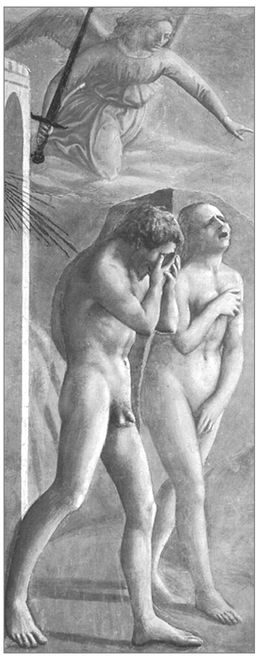

Ruskin admired Masaccio, especially his rendering of landscapes, but I find no reference in his writings to

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

It would be interesting to know what he thought of the figure of Eve. Like other female images the critic was familiar with, Masaccio's Eve has no pubic hair (one of Ruskin's biographers speculates that it was this feature of Effie's anatomy that caused him to drop her nightdress). Unlike them, she has the sexual characteristics of a mature woman. He might have viewed the painting as an allegory of his own wedding night: the man shielding his face in horror, the woman covering her swelling fields and winding cleft in shame. In this, he would have been hew-ing to the ancient scheme that classifies the genders as subject and object, viewer and viewed, knower and known.

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

It would be interesting to know what he thought of the figure of Eve. Like other female images the critic was familiar with, Masaccio's Eve has no pubic hair (one of Ruskin's biographers speculates that it was this feature of Effie's anatomy that caused him to drop her nightdress). Unlike them, she has the sexual characteristics of a mature woman. He might have viewed the painting as an allegory of his own wedding night: the man shielding his face in horror, the woman covering her swelling fields and winding cleft in shame. In this, he would have been hew-ing to the ancient scheme that classifies the genders as subject and object, viewer and viewed, knower and known.

Â

Masaccio,

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from The Garden of Eden

(1426â1428), Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine. Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from The Garden of Eden

(1426â1428), Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine. Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

But in the story of the Fall, both Adam and Eve are active seekers of knowledge, Eve even more than Adam. Both are

punished for knowing something they're not supposed to know. It may be the narcotic sweetness of a fruit whose name has been lost to us; it may be the shudder of concupiscence; it may be good and evil, those words that meant nothing until suddenly they meant everything. Just for a moment, Genesis confers on the sexes an odd equality, which it then takes away when Adam is given dominion over his wife. At the same time, both Adam and Eve are objects of knowledge, members of the class of the known. It's God who knows them, and it's his gaze they try to hide fromâat first so effectively that he calls out to them, “Where are you?” (Gen. 3:9). That a being who is supposed to be all seeing and all knowing must call, “Where are you?” to his creations is one of the story's most resistant mysteries, and one of its most poignant. To me, God's call is very poignant. It's like a parent's call to missing children. That, of course, is how many Christians read it, saying of the first couple not that they fell but that they strayed.

punished for knowing something they're not supposed to know. It may be the narcotic sweetness of a fruit whose name has been lost to us; it may be the shudder of concupiscence; it may be good and evil, those words that meant nothing until suddenly they meant everything. Just for a moment, Genesis confers on the sexes an odd equality, which it then takes away when Adam is given dominion over his wife. At the same time, both Adam and Eve are objects of knowledge, members of the class of the known. It's God who knows them, and it's his gaze they try to hide fromâat first so effectively that he calls out to them, “Where are you?” (Gen. 3:9). That a being who is supposed to be all seeing and all knowing must call, “Where are you?” to his creations is one of the story's most resistant mysteries, and one of its most poignant. To me, God's call is very poignant. It's like a parent's call to missing children. That, of course, is how many Christians read it, saying of the first couple not that they fell but that they strayed.

At once knower and known, the man and the woman are like people who look in a mirror for the first time and see themselves looking back. “And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they [were] naked.” (Gen. 3:7). To understand the vast gulf between the Greek and Hebrew worldviews, consider that Narcissus falls in love with his reflection and Adam and Eve recoil from theirs. But, then, they don't see themselves in a pond, but in each other's eyes. The eyeball is convex, and a convex mirror gives a distorted reflection. Maybe the first forbidden knowledge was how weak and uncomely they were in their nakedness, he with his drooping finger of prick and she with her lopsided tits and goosefleshed

bum. Their eyes were as merciless as teenagers'. And perhaps their nakedness was more than a condition of the body, and what they saw were the wens and stretch marks of each other's characters. Up until this moment, they hadn't even

had

characters, being only another species of animal; it's well known that no animal has a character until it is claimed by a human being. But now they had them. How lacking those characters were, how stunted and deficient! The man was easygoing, slothful, weak willed. The woman was greedy and shrill. And, really, she wasn't bright either. She'd believed what a snake had told her. He saw her and was disgusted with her person. She looked at him and thought, “He is not formed to excite passion.”

bum. Their eyes were as merciless as teenagers'. And perhaps their nakedness was more than a condition of the body, and what they saw were the wens and stretch marks of each other's characters. Up until this moment, they hadn't even

had

characters, being only another species of animal; it's well known that no animal has a character until it is claimed by a human being. But now they had them. How lacking those characters were, how stunted and deficient! The man was easygoing, slothful, weak willed. The woman was greedy and shrill. And, really, she wasn't bright either. She'd believed what a snake had told her. He saw her and was disgusted with her person. She looked at him and thought, “He is not formed to excite passion.”

Â

I'd had the house painted before we moved in, so it looked cleaner. F.'s attic study was now trimmed in Mediterranean blue. But the closets were still filled with the landlord's trash. The stove was broken and had a mouse nest inside it, and when we turned on the washing machine, it vomited gallons of hot water onto the floor of the barn. I got Rudy to buy a new stove and fix the washer, but by then F. had decided he was our enemy. The garbage might have been left as a taunt for her, as if Rudy had conferred with the vile old Broadway eminence who'd once accused her of dining on it. “Why don't you say something to him?” she'd reproach me. It bothered her that I didn't think he was our enemy. I'd remind her that I

had

said something; that was how we'd gotten the new stove. But whatever I'd said, I'd said mildly, making a joke out of what, even in the city, where landlords are permitted by law to seize your internal organs if you're late paying the rent, would have been

grounds for breaking the lease. I wanted Rudy to like me. Even now I'm embarrassed to admit it.

had

said something; that was how we'd gotten the new stove. But whatever I'd said, I'd said mildly, making a joke out of what, even in the city, where landlords are permitted by law to seize your internal organs if you're late paying the rent, would have been

grounds for breaking the lease. I wanted Rudy to like me. Even now I'm embarrassed to admit it.

At least the cats enjoyed the house. It had been built in the 1850sâby a black freedman, according to Rudy, who prided himself on knowing the history of the valleyâand then expanded with additions at either end, but it still had a long central aisle that was perfect for cats to scramble noisily up and down, especially late at night. Biscuit quickly staked a claim to the kitchen island. And all the cats liked roaming in the garden, with its lilac and apple trees, its beds of hosta, peonies, and day lilies in whose foliage small creatures nested, waiting to be killed. Out back there was a burrow occupied by a groundhog that looked like it must weigh thirty pounds. Once I saw it runningâcould Biscuit have had the nerve to chase it?âand thought I could feel the earth shake. Of all the cats, it was Gattino who seemed to be having the best time. He'd scuttle fearlessly up the smooth trunk of the horse chestnut that grew in the front yard and out onto branches fifteen feet above the ground, from where he surveyed the garden with a seigneurial air. “Gat-tini!” F. would trill to him, and he'd streak back down, half climbing, half leaping, and let her take him in her arms. I've always thought that a test of a cat's personality is whether it enjoys this and, if not, how long it will put up with it. Bitey resisted being picked up with every claw and fang. Biscuit protested at first but could be jollied into lying still for ten seconds or so. Gattino liked it. You could carry him around like a baby.

For the most part, he got along with the other cats. It helped that he was still young. He and Biscuit used to wage mock battles, darting and rearing, he on his long legs and she

on her short ones. But by now she was a full-grown cat, almost middle-aged. She lacked Gattino's energy and appetite for play, and there were times you could see her wearying of being pounced on when she was trying to get a drink of water or having him dive at her food bowl, not to eat but to bat bits of kibble around the floor. She'd done the same when she was a kitten, but she had put away kittenish things and knew not to play with her food any more. If I were nearby, I'd clap my hands to make him leave her alone. Once I blocked him roughly with my foot and locked him in my bedroom until Biscuit could finish eating. When I let him out fifteen minutes later, his high spirits were intact and he appeared to bear me no ill will, but I find it significant that I didn't tell F. about it.

on her short ones. But by now she was a full-grown cat, almost middle-aged. She lacked Gattino's energy and appetite for play, and there were times you could see her wearying of being pounced on when she was trying to get a drink of water or having him dive at her food bowl, not to eat but to bat bits of kibble around the floor. She'd done the same when she was a kitten, but she had put away kittenish things and knew not to play with her food any more. If I were nearby, I'd clap my hands to make him leave her alone. Once I blocked him roughly with my foot and locked him in my bedroom until Biscuit could finish eating. When I let him out fifteen minutes later, his high spirits were intact and he appeared to bear me no ill will, but I find it significant that I didn't tell F. about it.

Â

One moment from that autumn stays with me. I was in the living room, listening to a CD I'd put on the stereo, Joni Mitchell's

Ladies of the Canyon.

I hadn't listened to it in years and was a little surprised to realize I had it, or any of her albums, on CD. She seems so much an artist of vinyl; her voice, which you remember for its birdlike high notes but which has an unexpected deep end, needs physical grooves to rise out of, and only records have those. “Woodstock” came on, and suddenly my eyes were filled with tears. I walked into the kitchen. I didn't want the song to stop, but I needed distance from it. “What's wrong?” F. asked. I gestured helplessly at the speakers. “I don't know. It's beautiful, it's sad.” And then, “I want to get back to the garden.” I meant to say it jokingly, but my voice broke. F. started crying. “I do too.” We held each other.

Ladies of the Canyon.

I hadn't listened to it in years and was a little surprised to realize I had it, or any of her albums, on CD. She seems so much an artist of vinyl; her voice, which you remember for its birdlike high notes but which has an unexpected deep end, needs physical grooves to rise out of, and only records have those. “Woodstock” came on, and suddenly my eyes were filled with tears. I walked into the kitchen. I didn't want the song to stop, but I needed distance from it. “What's wrong?” F. asked. I gestured helplessly at the speakers. “I don't know. It's beautiful, it's sad.” And then, “I want to get back to the garden.” I meant to say it jokingly, but my voice broke. F. started crying. “I do too.” We held each other.

Â

Early that November, I spent a day working in the city. When I came back that night, Gattino was gone. F. had gone out to visit some friends; the cats had been in the garden. She'd considered calling him in, but she would only be away a little while, and it was still light. When she returned, the other cats were waiting by the back door. Gattino was nowhere in sight. That had been five hours ago. I told her it was too early to worry. The cats often stayed out late. We went out into the yard and called his name under the moon. I thought the problem might be that he hadn't heard F.âher voice is softâand I half expected him to come running in response to my manly bellow, hungry, his eye alight. It would be another thing I fixed, like F.'s laptop or the furnace that stopped putting out heat until I pushed its red reset button, which I knew how to do because of the instructions printed underneath. Of course I was forgetting the time I'd tried bleeding the radiator in my old loft. “GATTINO!” I yelled. “GATTINO!” My voice hung in the chill air. He didn't come.

The next day I called his name up and down the road that ran behind our house. It belonged to the college next door and filed past dormitories, woods, and a theater before emptying at length into a parking lot. Once, back in the summer, when I was clearing ailanthus from the garden, I'd looked up and seen a young woman walking down that road, bare breasted and martially erect, then turn and vanish into the dorm behind us. I imagine she was doing it on a dare. The few cars that passed now were traveling slowly, and I was reassured by the thought that if Gattino had wandered off this way, he was probably safe. I don't remember if it was that night or the next that F. looked

across Avondale Road, which ran past our front door, and realized, with a start of sick fear, that neither of us had thought of searching in that direction. In the few months Gattino had been going out, we'd always shooed him back from Avondale because there was so much traffic there and it moved so fast. Many years before, not a hundred feet from the house, a car had struck and killed a little girl who was crossing on her way to nursery school. The school was now named after her.

across Avondale Road, which ran past our front door, and realized, with a start of sick fear, that neither of us had thought of searching in that direction. In the few months Gattino had been going out, we'd always shooed him back from Avondale because there was so much traffic there and it moved so fast. Many years before, not a hundred feet from the house, a car had struck and killed a little girl who was crossing on her way to nursery school. The school was now named after her.

Other books

Glory and the Lightning by Taylor Caldwell

Sherwood by S. E. Roberts

Encyclopedia Brown Takes the Case by Donald J. Sobol

Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

Hooker to Housewife by Joy King

The Scandalous Son by UNKNOWN

Amy by Peggy Savage

Hidden Mercies by Serena B. Miller

The Godfather of Kathmandu by John Burdett