An Empire of Memory (16 page)

Read An Empire of Memory Online

Authors: Matthew Gabriele

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Social History, #Religion

why Compiègne is named after Charles the Bald.52 Hugh’s vita of St Sacerdos,

written for the monastery of Sarlat (in the Périgord) c.1107, does not mention the

Descriptio qualiter explicitly but seems to rely on it when Hugh recounts how he

had read elsewhere that Sarlat received a large piece of the True Cross from Charles,

who had brought the relic back with him from Jerusalem.53 The early twelfth-

century Gesta episcoporum Mettensium summarized the entire Descriptio qualiter up

to the death of Charlemagne, as did the early thirteenth-century Chronicon of

Martin of Troppau.54 Odo of Deuil, in describing the arrival of the Holy Tunic at

the priory of Argenteuil, used the Descriptio qualiter to explain how the relic made

its way from the East. Odo’s account, however, omitted Charles the Bald entirely.55

The entire Descriptio qualiter was included in the Vita Karoli Magni commissioned

by Frederick I Barbarossa for Charlemagne’s canonization in 116556 and can also

be found in Primat’s Roman des rois, later incorporated into the thirteenth-century

Grandes chroniques de France.57 The mid-twelfth-century Old French Le Pèlerinage

50 Hugh of Fleury, Liber de modernorum regum Francorum qui continent actus, MGH SS 9: 377.

51 This manuscript (Paris, Bib. Maz. MS 2013) is cited and discussed in Elizabeth A. R. Brown, and

Michael W. Cothren, ‘The Twelfth-Century Crusading Window of the Abbey of Saint-Denis:

Praeteritorum enim recordatio futurorum est exhibitio’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtald Institutes, 49 (1986), 14–15 n. 65. Its contents are described in detail in Jules Lair, ‘Mémoire sur deux

chroniques latines composées au XIIe siècle à l’abbaye de Saint-Denis’, Bibliothèque de l’École des

Chartes, 35 (1874), 567–8; and Auguste Molinier, Catalogue des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque

Mazarine, 4 vols. (Paris, 1886), ii. 321–3.

52 Hugh of Fleury, Historia Ecclesiastica: Fragmenta Fossatensis, MGH SS 9: 372–3. This dates to

c.1110.

53 Hugh of Fleury, Vita sancti Sacerdotis episcopis Lemovicensis, PL 163: 992. On the dating, see

Nico Lettinck, ‘Pour une édition critique de l’Historia Ecclesiastica de Hugues de Fleury’, Revue

Bénédictine, 91 (1981), 386.

54 Gesta episcoporum Mettensium, MGH SS 10: 538. It was likely written in the early 1120s under

Bishop Stephen (1120–63). Also, Martin of Troppau, Chronicon pontificum et imperatorum, MGH SS

22: 461–2.

55 The narrative is unpublished and survives in Oxford, Queen’s College, MS 348, fos. 48v–65v.

Elizabeth A. R. Brown and Thomas Waldman are currently completing an edn.

56 Vita Karoli Magni, in Die Legende, 17–93. The entire second book (of three) is devoted to

Charlemagne’s journey to Jerusalem. Charlemagne was canonized by the anti-pope Paschal III, but

Barbarossa and Pope Alexander III soon reconciled and the canonization was never formally recognized

by the Pope.

57 The section of the Grandes Chroniques concerning Charlemagne is translated in A Thirteenth-

Century Life of Charlemagne, tr. Robert Levine (New York, 1991), 70–91. A more critical edn. is Les

Grandes Chroniques de France, ed. Jules Viard, iii (Paris, 1923), 160–98.

Charlemagne’s Journey to the East

55

Figure 2.2. Scenes from the Jerusalem Crusade, Charlemagne Window, Chartres Cathedral.

Photo by Elizabeth Pastan, reprinted with permission.

de Charlemagne used the Descriptio qualiter as its primary source of inspiration.58

Even the thirteenth-century Old Norse Karlamagnús Saga used the Descriptio

qualiter, although likely filtered through the Pèlerinage.59

At Chartres, an early thirteenth-century stained-glass window, dedicated to

Charlemagne’s legendary conquests in Spain and the Holy Land, has six panels

depicting scenes from the Descriptio qualiter: Charles’s reception of the Eastern

envoys, the Byzantine ruler’s dream of Charlemagne, the defeat of the Muslims at

Jerusalem, Charles meeting the Byzantine ruler at the gates of Constantinople,

Charles receiving relics as gifts, and finally his presentation of the crown of thorns

to Aachen (Figure 2.2).60 The abbey church at Saint-Denis had a window, a mid-

twelfth-century creation, with fourteen medallions linking the Descriptio qualiter to

58 Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne, tr. Glyn S. Burgess (Edinburgh, 1998). On the relationship

between the Descriptio qualiter and Le Pèlerinage, see Anne Latowsky, ‘Charlemagne as Pilgrim?

Requests for Relics in the Descriptio qualiter and the Voyage of Charlemagne’, in Legend of

Charlemagne, 153–67.

59 Karlamagnús Saga: The Saga of Charlemagne and his Heroes, tr. Constance B. Hieatt (Toronto,

1980), 181–205.

60 Description from Clark Maines, ‘The Charlemagne Window at Chartres Cathedral: New

Considerations on Text and Image’, Speculum, 52 (1977), 805–8. Also now see Pastan,

‘Charlemagne as Saint?’, 97–135.

56

The Franks Remember Empire

the First Crusade (Figure 2.3). The first two medallions portray generalized scenes

of crusading, the second two medallions show Charlemagne being summoned to

the East by Byzantine envoys, then meeting the Byzantine ruler at Constantinople,

and the final ten panels illustrate various scenes from the inception of the First

Crusade through the battle of Ascalon.61 By the thirteenth century one writer could

comfortably state what the Saint-Denis window had suggested––that the crusade of

1095 was actually the Second because Charlemagne had staged the First.62

As the last few examples imply, the Descriptio qualiter has been thought of as the

narrative of ‘Charlemagne’s crusade’, with the text necessarily emerging from the

contemporary experience of the First Crusade.63 These scholars have latched onto

the martial nature of Charlemagne’s journey to the East, further noting the text’s

condescension towards the Eastern empire, as well as the Byzantine call for help

to the West. Yet it seems mistaken to link the Descriptio qualiter too closely to

crusading. For example, Alexius’ call for help at Piacenza in 1095 was not the first

time he had asked the West for military assistance, having done so numerous times

between 1071 and 94. Although the Greek emperor rates below Charles in the

Descriptio qualiter, its portrayal of the Byzantine ruler is generally laudatory, very

unlike his portrayal in Einhard’s Vita Karoli and Benedict of St Andrew’s Chronicon

(let alone the narratives of the First Crusade).64

Additionally, the two most outstanding facets of crusading––Jerusalem and the

Muslims––hardly figure in the narrative at all. The emphasis the author places on

Constantinople (especially as the location of the relics Charlemagne returns with),

as well as his mention of Ligmedon, may suggest the author’s familiarity with the

contemporary practicalities of pilgrimage. However, he shows almost no interest in

the Holy Land more generally.65 Jerusalem receives barely a mention, not even a

token amount of rejoicing can be heard once Charles has rid the city of the

befouling menace that plagued it. This is a far cry from the rhetoric deployed by

Urban II, the crusaders, or their later narrators in the West.66 Moreover, the

61 Brown and Cothren, ‘Crusading Window’, 1–38.

62 Alberic of Trois-Fontaines, Chronicon, MGH SS 23: 804. The text is mid-13th cent.

63 For examples in modern scholarship, see Giosuè Musca, Carlo Magno ed Harun al Rashid (Bari,

1963), 78; and Paul Rousset, Les Origines et les caractères de la Premiére Croisade (New York, 1978), 41.

64 On Alexius and the West, see M. de Waha, ‘La Lettre d’Alexis I Comnène à Robert le Frison:

Une revision’, Byzantion, 47 (1977), 119. On Charles’s relations with the Byzantines, Descriptio

qualiter, ed. Rauschen, 110–12; Einhard, Vita Karoli, 20; Benedict, Chronicon, 711. Much hostility

towards the Byzantine empire is also found in the narratives of the First Crusade. Jonathan Riley-

Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading (Philadelphia, 1986), 108. On East–West relations

generally, see Jonathan Harris, Byzantium and the Crusades (London, 2003); Christopher Macevitt,

The Crusades and the Christian World of the East: Rough Tolerance (Philadelphia, 2007); and Brett

Whalen, Dominion of God: Christendom and the Apocalypse in the Middle Ages (Cambridge, Mass.,

2009).

65 Folz, Souvenir, 180; Marc du Pouget, ‘Recherches sur les chroniques latines de Saint-Denis:

Édition critique et commentaire de la Descriptio clavi et corone domini et de deux séries de textes relatifs à la légende carolingienne’, Positions des thèses soutenues par les élèves de la promotion de 1978 pour obtenir le diplôme d’Archiviste Paléolgraphe, Bibliothèque de l’École des Chartes (Paris, 1978), 43.

66 There is also no mention of the Holy Sepulcher, which, Sylvia Schein argues, was the original

objective of the First Crusade. See Sylvia Schein, ‘Jérusalem: Objectif originel de la Première

Croisade?’, in Michel Balard (ed.), Autour de la Première Croisade: Actes du colloque de la Society for

Charlemagne’s Journey to the East

57

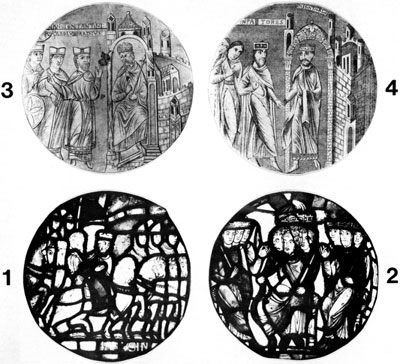

Figure 2.3. Reconstruction of lower registers of Crusading Window, Saint-Denis. Re-

printed with permission from Elizabeth A. R. Brown and Michael W. Cothren, ‘The

Twelfth-Century Crusading Window of the Abbey of Saint-Denis: Praeteritorum enim

recordatio futurorum est exhibitio’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtald Institutes, 49

(1986), 1–40.

Muslims of the Descriptio qualiter seem to be little more than straw men––nothing

but generic pagans, who are quickly swept aside by Charles and excised from the

narrative in only two sentences. The roughly contemporary Oxford Chanson de

Roland, even with all of its misconceptions about Islam, exhibits a better under-

standing of, and thoughtfulness about, the Muslims than does the Descriptio

qualiter. Although an armed expedition to Jerusalem against the Muslims is the

ostensible reason for Charlemagne’s expedition to the East, it seems more of an

excuse to get him to Constantinople and get powerful christological relics into his

hands.

Most scholars date the Descriptio qualiter to the last quarter of the eleventh

century, hinging their discussions about the Descriptio qualiter’s provenance upon a

sentence towards the end of the narrative that has Charlemagne establish the feast

of Lendit to celebrate the christological relics with which he had returned from

Constantinople.67 The narrative announces Lendit as occurring in the second week

the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East (Clermont-Ferrand, 22–25 juin 1995) (Paris, 1996),

119–26; repr. in Sylvia Schein, Gateway to the Heavenly City: Crusader Jerusalem and the Catholic

West (1099–1187) (Burlington, Vt., 2005), 9–20. The Descriptio qualiter is, however, closer in tone to Gregory VII’s ‘proto-crusade’ letters of 1074, especially in their shared focus on the Byzantines. See H. E. J. Cowdrey, ‘Pope Gregory VII’s “Crusading” Plans of 1074’, in B. Z. Kedar, H. E. Mayer, and

R. C. Smail (eds.), Outremer: Studies in the History of the Crusading Kingdom of Jerusalem (Jerusalem, 1982), 27–40; and the discussion in Ch. 5, below.

67 These scholars most prominently include Gaston Paris, Gerhard Rauschen, Robert Folz, and

Marc du Pouget. Gaston Paris, Histoire poétique de Charlemagne, 2nd edn. (Paris, 1905), 56; Rauschen,

Die Legende, 99–100; Folz, Souvenir, 179 n. 111; du Pouget, ‘Recherches’, Positions des thèses, 43; and 58

The Franks Remember Empire

of June, when the Church celebrated the Ember Days.68 Observed in the Western