America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (31 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

George P.A. Healy’s famous 1868 painting, “The Peacemakers”, depicts the meeting at City Point

Lee’s siege lines at Petersburg were finally broken on April 1 at the Battle of Five Forks, which is best remembered for General George Pickett (best remembered for Pickett’s Charge) enjoying a cod bake lunch while his men were being defeated. Historians have attributed it to unusual environmental acoustics that prevented Pickett and his staff from hearing the battle despite their close proximity, not that it mattered to the Confederates at the time. Between that and Gettysburg, Pickett and Lee were alleged to have held very poor opinions of each other by the end of the war, and there is still debate as to whether Lee had ordered Pickett out of the army during the Appomattox campaign. The following day, battles raged across the siege lines of Petersburg, eventually spelling the doom for Lee’s defenses. On April 2, 1865, Lee abandoned Petersburg, and thus Richmond with it.

Lee’s battered army began stumbling toward a rail depot in the hopes of avoiding being surrounded by Union forces and picking up much needed food rations. While Grant’s army continued to chase Lee’s retreating army westward, the Confederate government sought to escape across the Deep South. On April 4, President Lincoln entered Richmond and toured the home of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Fittingly, the food rations did not arrive as anticipated. On April 7, 1865, Grant sent Lee the first official letter demanding Lee’s surrender. In it Grant wrote, “The results of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel it is so, and regret it as my duty to shift myself from the responsibility of any further effusion of blood by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate States army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.”

[11]

When Lee proposed to hear the terms, the communications continued until April 9, when the two met at Appomattox Court House. When Lee and Grant met, the styles in dress captured the personality differences perfectly. Lee was in full military attire, while Grant showed up casually in a muddy uniform. The Civil War’s two most celebrated generals were meeting for the first time since the Mexican-American War.

The McLean Parlor in Appomattox Court House. McLean’s house was famously fought around during the First Battle of Bull Run, leading him to move to Appomattox.

The Confederate soldiers had continued fighting while Lee worked out the terms of surrender, and they were understandably devastated to learn that they had surrendered. Some of his men had famously suggested to Lee that they continue to fight on. Porter Alexander would later rue the fact that he suggested to Lee that they engage in guerrilla warfare, which earned him a stern rebuke from Lee. As a choked-up Lee rode down the troop line on his famous horse Traveller that day, he addressed his defeated army, saying, “Men, we have fought through the war together. I have done my best for you; my heart is too full to say more.”

Appomattox is frequently cited as the end of the Civil War, but there still remained several Confederate armies across the country, mostly under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston, who Lee had replaced nearly 3 years earlier. On April 26, Johnston surrendered all of his forces to General Sherman. Over the next month, the remaining Confederate forces would surrender or quit. The last skirmish between the two sides took place May 12-13, ending ironically with a Confederate victory at the Battle of Palmito Ranch in Texas. Two days earlier, Jefferson Davis had been captured in Georgia.

Although the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Potomac at Appomattox Courthouse did not officially end the long and bloody Civil War, the surrender is often considered the final chapter of the war. For that reason, Appomattox has captured the popular imagination of Americans ever since Lee’s surrender there on April 9, 1865.

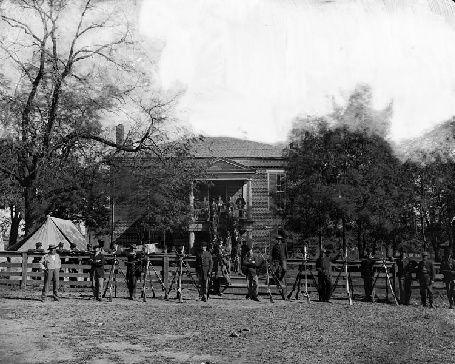

Appomattox Court House in 1865

Chapter 6: Post-War Public Perception, 1865-1869

Master Strategist or Careless Butcher?

Although Grant had succeeded in ending the conflict and setting the groundwork for reuniting the war-torn nation, he was not without his detractors regarding his leadership abilities in the war, among whom were many Northerners. While most of the North accepted that “a victory is a victory,” many from both sides attributed Lee’s eventual surrender as merely a “matter of numbers”, not as a result of Grant’s superior strategy. After all, Grant’s army vastly outnumbered Lee’s. Many critics even labeled him a “butcher” for using basic tactics that resulted in such a huge loss of life.

Still, many came to reason that while it was true that the Union had numerical superiority in Virginia, the fact was, they

always

had. From the very first battle at Bull Run in July of 1861, the Union had greater numbers, but Grant had been the first leader to make these numbers work to a Union advantage. And in the final analysis, Grant’s administrative abilities, the training that enabled him to manage both supplies and men, had played a significant role in achieving victory; perhaps the most significant role. And as military historians point out, prior to Grant taking command of the Union Armies, there had been no coordination whatsoever between the various forces. Once Grant was in charge, he had fourteen officers on his staff riding day and night to corps and division commanders with advice, orders, encouragement, and requests for updates. Once Grant was in charge, rather than meander haphazardly from battle to battle, the Northern armies moved upon and around the Confederate forces with precision.

Physical Appearance

As General Horace Porter explains in the autobiographical

Campaigning With Grant

, due to a number of popular photographs of Grant (shot from a distance rather than the product of formal poses), his persona as a burley and robust battle-hardened warrior, and his association with laboring tirelessly the fields, a physical image circulated after the war that little reflected Grant the man.

In fact, those fortunate enough to actually meet him were surprised to find that he was actually of slim build (weighing only one hundred thirty-five pounds), stood just 5 feet, eight inches tall (which when combined with his natural stoop made him appear even shorter), and projected a gentleness of manner that most found quite disarming. Grant’s reputation as a tenacious bulldog may have been present on the battlefield, but Grant the man was not the brutish, physically imposing individual many still think he was.

Porter, who served as Grant’s general-in-staff from 1864 to the end of the war, described Grant’s general appearance: “His hair and beard were of a chestnut-brown color. The beard was worn full, no part of his face being shaved but like his hair, was always kept closely and neatly trimmed. Like…several other great men in history, he had a wart on his cheek. His brow was high, broad, and rather square and was creased with several horizontal wrinkles which helped to emphasize the serious and somewhat careworn look which was never absent from his countenance.”

[12]

Grant during the war

However, the widely-accepted rumor of Grant as a sloppy, even careless dresser, was apparently quite true. Often described as one of the worst dressed officers in any army, Grant was known to appear at formal military meetings “out of uniform”--perhaps wearing part of his uniform, perhaps not--and was often seen in various states of undress while commanding troops in the field. Even at what was one the most momentous events of his career, Lee’s surrender at Appomattox (which he knew would be recorded for posterity), Grant’s dressed was described as “like a lowly private,” wearing a dirty sack coat and ill-fitting fatigue coat, his shirt visible, and carrying no side arms whatsoever. Many thought it fortunate that Grant’s activities were confined to the battlefield.

Persona and Path to the White House

In spite of the critics, Grant understandably held a very lofty position at the end of the Civil War, in terms of both political and military clout. Soon after the war, Grant transferred his headquarters to Washington and set about helping to reconstruct the country. But almost immediately, he found himself embroiled in a bitter conflict between President Andrew Johnson and the group of congressmen known as the Radical Republicans. The “Radicals” demanded harsh treatment of the former “enemies of the state” but strict protection of the rights of the Blacks. Johnson planned to make an example of Robert E. Lee in particular by making him stand trial for treason, but he wanted to institute policies that restricted Blacks’ rights. Grant stepped forward to remind Johnson of the terms of the surrender at Appomattox, impressing upon him that it was time to let the nation mend. Grant also opposed Johnson’s interference with military commanders sent into the South to carry out Reconstruction policies, and he let his sentiment known.

In late 1865, Grant toured the South at Johnson’s behest, subsequently reporting that he was greeted with surprising friendliness everywhere he went, after which he recommended a lenient Reconstruction policy. On July 25, 1866, Congress established a new rank, that of General of the Armies of the United States, to which Grant was immediately appointed.

In July of 1867, President Johnson informed Grant that he intended to remove Edward M. Stanton as the Secretary of War in order to test the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act, passed by congressional Republicans, requiring Congressional approval for such removals from office. On August 12, Grant was ordered to serve as Secretary

ad interim

. When Congress convened in January of 1868 and demanded that Stanton be reinstated, Grant relinquished the office, infuriating Johnson, and effectively cementing Grant’s ties to the Republican Party. Subsequently, when the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago on May 21, 1868, Grant was nominated almost unanimously to be the party’s candidate for President. In his acceptance letter to the Republican Election Committee, Grant ended with the statement, “Let us have peace”, which became the Republican campaign slogan.

Chapter 7: Grant’s Presidency, 1869 to 1877

Winning the Presidency

In the Election of 1868, Grant emerged with a popular majority vote over the Democratic opponent, former New York State Governor Horatio Seymour, winning only by 306,000 votes out of a total 5,715,000 cast. Surprisingly enough, Grant was the first West Point graduate to become President of the United States. While the issue hadn’t been considered prior to the election, the marginal win reflected the precarious state of the nation and the need for the Republicans to reassert control over the South if peace was to become a reality.