America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (27 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

When his unit was ordered to Louisiana in May of 1844, however, it derailed both his plans to marry, as well as his application to West Point as assistant teacher of mathematics. But before leaving for his post, he convinced Julia to a secret engagement, not getting her parents’ official blessing until a year late while he was back on leave in April of 1845. When his duty was fulfilled in the Mexican-American War in July of 1848, Grant immediately sailed to St. Louis to claim his betrothed. Married on August 22, 1848, Julia became what is widely described as a devoted wife who gave Grant constant encouragement.

The Grants went on to have 4 children, including Frederick Dent Grant (who later became aide-de-camp for General Sherman), Ulysses S. "Buck" Grant, Jr. (who later served as his father’s White House secretary); Ellen "Nellie" Grant; and Jesse Root Grant (who would run for President in 1908). The beard that helps identify Grant in pictures during the Civil War would come about because of a letter Julia wrote while he was in Mexico, in which she described a dream in which he had a beard. No fool, Grant came back from that war with facial hair.

Julia with daughter Nellie, son Jesse, and her father

Business Ventures and Personal Failures

By mid-1854, Grant was settled on 80 acres given to him by Julia’s father on the Dent White Haven Estate, and he went about doing what he knew best: farming. Naming his spread “Hardscrabble”--all homes were named, per tradition--Grant build a log house almost single-handedly, where he and his family lived from 1855-1858. But aside from the joy of his expanding family, over the next six years Grant’s life was one abject failure after another.

1891 photo of “Hardscrabble”

Persistent ill-health (probably malaria picked up in Mexico), dropping crop prices following the Panic of 1857 (the world's first world-wide economic crisis), and then rejection of his application for the post of St. Louis County engineer (because he’d aligned himself with the Democratic rather than Republican Party) all drove Grant into a deep depression. He even reached a point where he had to peddle firewood in St Louis to bring in money, and one Christmas things were so bad he had to pawn his father’s watch to buy gifts for Julia and his children.

In 1859, after years of disappointment and failure as a farmer, Grant sold his farm, freed his only slave, and moved to St. Louis, where a relative gave him a job in a real estate office. Even there, Grant quickly gave up because he didn’t have the intestinal fortitude to collect overdue rent from tenants. He then obtained and quickly lost a job in the U. S. Customs House.

Finally, in May 1860, Grant accepted a job in a leather goods store owned by his father and brothers in Galena, Illinois. At the time, Galena was one of Illinois' largest and most influential cities, with a population of nearly 12,000, and had been the largest river boat port north of St. Louis for 20 years. Galena also served as a gateway for settlers moving north and west. But even with commerce bustling and booming around him, Grant couldn’t do better than the $50-a-month job his father provided him as a store clerk. And even at that, he showed no aptitude.

At the end of 1860, the only thing Grant had succeeded at was his military service in Mexico, and it was in a role he held little interest in. But, like many Americans, Grant could see the impending Civil War on the horizon. Despite having virtually zero support in the slave states, Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln ascended to the presidency at the head of a party that was not yet 10 years old, and one whose stated goal was to end the expansion of slavery. Although Lincoln did not vow to abolish slavery altogether, Southerners believed Lincoln’s presidency constituted a direct threat to the South’s economy and political power, both of which were fueled by the slave system. Southerners also perceived the end of the expansion of slavery as a threat to their constitutional rights, and the rights of their states, frequently invoking northern states’ refusals to abide by the Fugitive Slave Act. South Carolina seceded shortly after Lincoln’s election in November 1860, and with talk of war on the horizon, it’s likely Grant saw it as a way to finally make a steady income and erase the memories of some of his failures.

Chapter 5: The Civil War

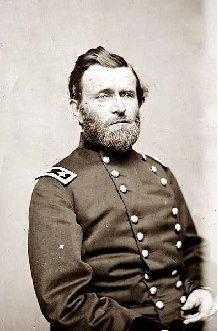

Brigadier General Grant

The Outbreak of War

Lincoln’s predecessor was among those who could see the potential conflict coming from a mile away. While still in office, President James Buchanan instructed the federal army to permit the Southern states to take control of forts in its territory, hoping to avoid a war. Conveniently, this also allowed Southern forces to take control of important forts and land ahead of a potential war, which would make secession and/or a victory in a military conflict easier. Many Southern partisans in federal government in 1860 took advantage of these opportunities to help Southern states ahead of time.

One of the forts in the South was Fort Sumter, an important but undermanned and undersupplied fort in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Buchanan attempted to resupply Fort Sumter in the first few months of 1860, but the attempt failed when Southern sympathizers in the harbor fired on the resupply ship. In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln promised that it would not be the North that started a potential war, but he was also aware of the possibility of the South initiating conflict. After he was sworn in, Lincoln sent word to the Governor of South Carolina that he was sending ships to resupply Fort Sumter, to which the governor replied demanding that federal forces evacuate it. Southern forces again fired on the ship sent to resupply the boat, and on April 12, 1861, Confederate artillery began bombarding Fort Sumter itself. After nearly 36 hours of bombardment, Major Robert Anderson called for a truce with Southern forces led by P.G.T. Beauregard, and the fort was officially surrendered on April 14. No casualties were caused on either side by the dueling bombardments across the harbor, but, ironically, two Union soldiers were killed by an accidental explosion during the surrender ceremonies.

After the attack on Fort Sumter, support for both the northern and southern cause rose. President Lincoln requested that each loyal state raise regiments for the defense of the Union, with the intent of raising an enormous army that would subdue the rebellion. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Grant felt he had an obligation to fight for the Union. Presiding over a Galena war meeting called in response to President Lincoln’s call-to-arms, Grant took responsibility for recruiting, equipping, and drilling the Jo Daviess Guards, a unit named in honor of Major Joseph Hamilton Daviess, who was killed in 1811 at the Battle of Tippecanoe. Grant then accompanied them to Springfield, the state capital, where Governor Richard Yates appointed him an aide and assigned him to duty in the state adjunct general’s office, where his knowledge of military practice helped establish the area units’ mustering procedure.

On June 15, 1861, Governor Yates appointed Grant colonel of a decidedly “unruly” regiment called the 21

st

Illinois Volunteers, which had already driven a lesser-qualified commander into early retirement. Assigned to northeastern Missouri, Grant was then promoted to brigadier general by President Lincoln, even before he’d engaged the enemy, due to the influence of U. S. Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, from Galena. Grant chose John A. Rawlins, a local lawyer, to serve as his chief-of-staff. Rawlins soon became Grant’s closest advisor, critic, defender, and friend.

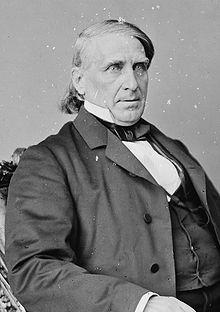

Washburne

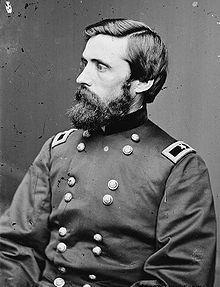

Rawlins would later become Grant’s Secretary of War and was zealous in his effort to defend Grant’s reputation during the Civil War

The Union’s First Major Victories: Fort Henry and Fort Donelson

Despite the loss of Fort Sumter, the North expected a relatively quick victory, and their expectations weren’t unrealistic, given the Union’s overwhelming economic advantages over the South. At the start of the war, the Union had a population of over 22 million. The South had a population of 9 million, nearly 4 million of whom were slaves. Union states contained 90% of the manufacturing capacity of the country and 97% of the weapon manufacturing capacity. Union states also possessed over 70% of the total railroads in the pre-war United States at the start of the war, and the Union also controlled 80% of the shipbuilding capacity of the pre-war United States.

But while the Lincoln Administration and most Northerners were preoccupied with trying to capture Richmond in the summer of 1861, it would be the little known Grant who delivered the Union’s first major victories, over a thousand miles away from Washington. Grant’s new commission led to his command of the District of Southeast Missouri, headquartered at Cairo, after he was appointed by “The Pathfinder”, John C. Fremont, a national celebrity who had run for President in 1856. Fremont was one of many political generals that Lincoln was saddled with, and his political prominence ensured he was given a prominent command as commander of the Department of the West early in the war before running so afoul of the Lincoln Administration that he was court-martialed.