America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (28 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

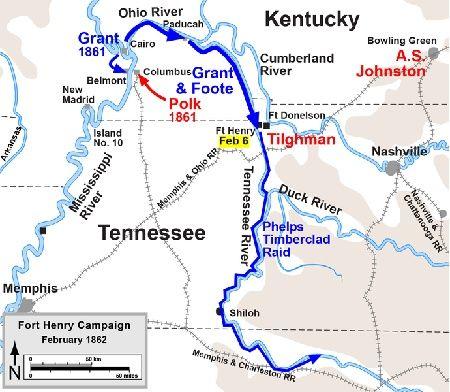

Regardless of how Grant got to the position he did, he immediately began to reveal his strategic military competence. On September 6, 1861, Grant quickly seized a strategic position at Paducah, Kentucky at the mouth of the Tennessee River. Grant’s men first fought at Belmont, Missouri on November 7, a diversionary attack that proved inconclusive after the Union forces were initially successful but the Confederates were able to quickly rally and hold the field. But had it not been for Grant’s decisiveness, his men may not have gotten out alive. He was credited with demonstrating exceptional independent initiative, quick decision-making, and fought aggressively to protect his men.

Map of the Fort Henry and Fort Donelson Campaign

Unhappy that his regiment was being used only for defensive and diversionary purposes, in January of 1862, Grant persuaded General Henry W. Halleck to allow his men to launch a campaign on the Tennessee River. As soon as Halleck acquiesced, Grant moved against Fort Henry, in close coordination with the naval command of Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote. The tag team of infantry and naval bombardment helped force the capitulation of Fort Henry on February 6, 1862.

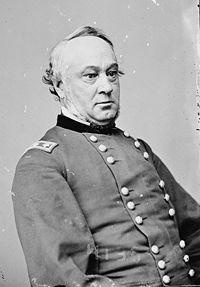

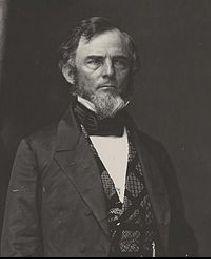

Henry “Old Brains” Halleck was noted for his strategical military acumen before the war and would later become general-in-chief until 1864, when he was replaced by Grant.

The surrender of Fort Henry was followed immediately by an attack on Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, which earned Grant his famous nickname “Unconditional Surrender”. As Grant’s forces enveloped the Confederate garrison at Fort Donelson, which included Confederate generals Simon Buckner, John Floyd, and Gideon Pillow. In one of the most bungled operations of the war, the Confederate generals tried and failed to open an escape route by attacking Grant’s forces on February 15. Although the initial assault was successful, General Pillow inexplicably chose to have his men pull back into their trenches, ostensibly so they could take more supplies before their escape. Instead, they simply lost all the ground they had taken, and the garrison was cut off yet again.

During the early morning hours of February 16, the garrison’s generals held one of the Civil War’s most famous councils of war. Over the protestations of cavalry officer Nathan Bedford Forrest, who insisted the garrison could escape, the three generals agreed to surrender their army, but none of them wanted to be the fall guy. General Floyd was worried that the Union might try him for treason if he was taken captive, so he turned command of the garrison over to General Pillow and escaped with two of his regiments. Pillow had the same concern and turned command over to General Buckner before escaping alone by boat. Meanwhile, Forrest successfully rallied about 4,000 troops and fought through the siege across the river.

Despite all of these successful escapes, General Buckner decided to surrender to Grant. As a long-standing legend describes, when asked for terms of surrender, Grant sent a letter stating, “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender.”

[9]

Forrest

Floyd

Buckner

Pillow

Grant’s campaign was the first major success for Union forces in the war, which had already lost the disastrous First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 and was reorganizing the Army of the Potomac in anticipation of the Peninsula Campaign, which would fail in the summer of 1862. As the Union’s first major victory, word of Grant’s decisive actions spread throughout the U. S. Army--giving rise to the accolade that his initials stood for “Unconditional Surrender.”

The Battle of Shiloh

A replica of Shiloh Church. The original was ruined during the battle.

Grant had just secured Union command of precious control over much of the Mississippi River and much of Kentucky and Tennessee, but that would prove to be merely a prelude to the Battle of Shiloh, which at the time was the biggest battle ever fought on the continent.

After the victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, Grant was now at the head of the Army of the Tennessee, which was nearly 50,000 strong and firmly encamped at Pittsburg Landing on the western side of the Tennessee River. The losses had dismayed the Confederates, who quickly launched an offensive in an attempt to wrest control of Tennessee from the Union.

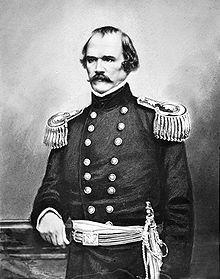

At the head of the Confederate army was Albert Sidney Johnston, President Jefferson Davis’s favorite general, and widely considered the South’s best general. On the morning of April 6, Johnston directed an all out attack on Grant’s army around Shiloh Church, and though Grant’s men had been encamped there, they had failed to create defensive fortifications or earthworks. They were also badly caught by surprise. With nearly 45,000 Confederates attacking, Johnston’s army began to steadily push Grant’s men back toward the river.

As fate would have it, the Confederates may have been undone by friendly fire at Shiloh. Johnston advanced out ahead of his men on horseback while directing a charge near a peach orchard when he was hit in the lower leg by a bullet that historians now widely believe was fired by his own men. Nobody thought the wound was serious, including Johnston, who continued to aggressively lead his men and even sent his personal physician to treat wounded Union soldiers taken captive. But the bullet had hit an artery, and Johnston began to feel faint in the saddle. With blood filling up his boot, Johnston unwittingly bled to death.

Johnston

Johnston’s death was hidden from his men, and command fell upon P.G.T. Beauregard, who was the South’s hero at Fort Sumter and at the First Battle of Bull Run. General Beauregard was competent, but Johnston’s death naturally caused a delay in the Confederate command. It was precious time that Grant and General Sherman used to rally their troops into a tight defensive position around Pittsburg Landing. The following morning, Grant’s army, now reinforced by Don Carlos Buell’s 20,000 strong Army of the Ohio, launched a successful counterattack that drove the Confederates off the field and back to Corinth, Mississippi.