All the King's Cooks (12 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

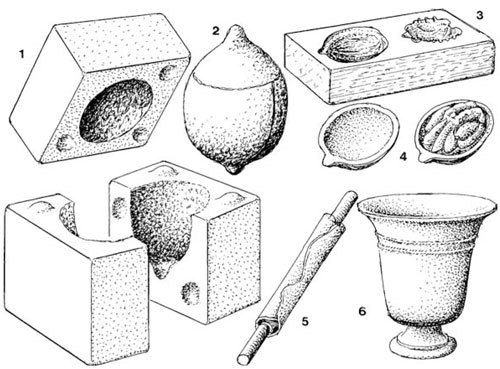

15.

Sugar moulds

Tudor sugar-moulding was a highly skilled craft. Here are (1) the sectional plaster moulds used to cast lemons (2) in boiling sugar; the carved wooden press-mould (3) for making walnut shells and kernels (4); and the equally realistic cinnamon sticks (5) and porcelain-like drinking cups (6), also made in finely flavoured sugar plate.

Back in the Pastry Yard after our visit to the confectionary, we

find that the next doorway led into the room below, the pastry, where almost every variety of pasty, pie and tart was baked for the royal household. Its sergeants, John Jenyns in 1540–2, succeeded by John Heath before he transferred to the bakehouse, and its clerk Anthony Weldon, were responsible for ensuring that ‘all their baked Meates [were] well seasoned and served … without imbesselment or giveing away any of the same; and also that there be no wastefull expences made of any Flower or Sawce within the said Office’.

30

Before eight every morning, the clerk had to deliver to the clerk of the kitchen the brief that detailed the previous day’s consumption of foodstuffs in the bakehouse, and once a month submit his ‘parcel’ of requests for fresh supplies to the counting house. The Pastry’s administrative office was on the first floor, beyond the confectionary, while the sergeant’s and clerk’s lodgings, along with those of their six yeomen, their grooms and four ‘conducts’, or labourers, were in the first-floor chambers and second-floor garrets – warm and dry over the main pastry workhouses.

There were three working rooms in the pastry, the first and smallest (no. 25) of which was probably the storehouse and boulting house for the various flours used there. These probably included wholemeal for the coarsest pastry, and from which the conducts would sift the bran to produce wheatmeal flour for common pastry, or sift again through finer sieves to produce unbleached white flour for the finer pastries. Next door (no. 24), was the main pastry workhouse, where the practical pastry-making was carried out.

Of all the foods prepared here, by far the largest and most impressive were the venison pasties made with deer either hunted in the royal parks or presented as gifts to the King – such as the stags brought from Waltham Forest to Hampton Court in August 1530, or the Windsor venison that arrived in June 1531.

31

Pies of all kinds of meats, fish and fruits would also be baked here, along with open-topped tarts and custards.

Usually a number of empty tart cases would be baked, these being filled with a variety of prepared mixtures which had only to be cooked for a relatively short period. This was a sensible system for the large-scale catering necessary for great households such as Hampton Court, since the cases could be baked in the ovens while they were still hot from preparing supper for four o’clock, then stored until required for uses. In addition, this method ensured that their bases were cooked properly, neither soggy nor underdone as they would have been if baked when full of moist fillings.

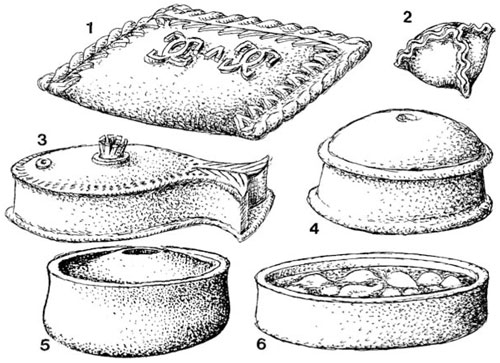

16.

Venison

Venison for the King’s table came from his frequent hunting expeditions, from the royal parks, or as gifts from courtiers. These harts are from George Turberville’s

Boke of Hunting

of 1576.

All the pies and pasties made in the pastry were baked in the adjacent pastry bakehouse (no. 23). Four ovens were built in its west wall by Gabryell Dalton in 1530; all were constructed with shallow domed roofs made of tiles set edge to edge to resist the effects of the constant fierce heat followed by gradual cooling.

32

The largest measured over twelve feet (3.7m) in diameter – ideal for all the largest pasties. In front of the ovens, extending across one third of the pastry bakehouse ceiling, was a huge smoke-hood shaped like a half-pyramid, designed to carry away all the smoke that issued from the oven mouths as they were fired up to temperature, just like those in the Outer Court bakehouse.

Unlike many of the other foods prepared in the kitchens, pastries could be kept fresh for quite a few days after being baked, so long as they remained cool and dry. For this reason, the north-facing room just to the east of the pastry was used as a dry larder (no. 28). Pre-empting modern food hygiene regulations by four and a half centuries, the Tudor cooks fully appreciated the need to keep raw and cooked foods separate if outbreaks of food-poisoning were to be avoided. By storing its finished goods here, the Pastry was able to maintain a reservoir of supplies ready to be whisked off down the Paved Passage to the servery hatches.

17.

Pasties and Pies

Tudor pasties and pies were made in a variety of shapes. Here we see venison pasties (1) marked with an appropriate V, based on an illustration from Robert May’s

The Accomplish’t Cook

(1660); and a smaller triangular pasty (2) as recommended by Thomas Dawson. Some raised pies, like May’s salmon pie (3), used their shape to indicate their contents, while others resembled modem pork pies (4) or had their lids blown up using a straw before being put into the oven (5). This one, together with the open-topped tart (6), is based on an engraving showing James I entertaining the Spanish ambassadors in 1623.

The Paved Passage

Larders, Boiling House, Workhouses

Between the Pastry Yard, the main kitchens and the Privy Orchard to the north lay a block of larders and preparation kitchens, all entered from a narrow central corridor open to the sky. Known as the Paved Passage up to the late seventeenth century at least, it is now called Fish Court (no. 27).

The larder where the raw meat was stored was located at the centre of the Paved Passage’s southern wall (no. 33). The meat delivered here was already butchered; the sergeant of the acatery who organised its transport on the hoof from the royal estates or the markets would have arranged the messy, noisy, smelly slaughtering well away from the main palace buildings. He and his officers took specified parts of each carcase as their fee: the sergeant received the head, tongue, midriff, paunch and four feet of each ox, while the yeoman and groom had its belly-piece, rump, and ‘sticking-piece’ along with the head, caul, ‘gatherings’ (heart, liver and lungs) and feet of each sheep; and the clerk got the head and skin of each veal calf.

1

On arriving at the palace kitchens, the carcases would be brought through the Back Gate to the door leading from the Pastry Yard into the boiling house (no. 26) and from there into the larder. Here ventilation was very important for keeping the

meat fresh, although the throughput must have been very rapid when the court was in residence. In the Larder, the meat was inspected by James Mitchell, sergeant of the larder, and its quantity recorded by his clerk, Anthony Weldon.

2

In 1541 Weldon had been granted both the income from the town of Penlosse in northwest Wales and the passage of boats to Conway, etc. By 1543 he was clerk of the pastry, and then promoted to second clerk of the kitchen, while in 1544, when he returned to the larder, he received the lease of the manor of Swanscombe in Kent. Weldon had done well for himself. But it was not unusual for officers to substantially improve their income through service in the household.

3

18.

The Paved Passage

Now known as ‘Fish Court’, this passageway provided the main means of communication between the larders, the boiling house, the pastry, the workhouses and the main kitchens. The upper rooms were used as lodgings for the staff who worked in the rooms directly below, the larder staff sleeping over the larders to the left.

The work cycle began here in the larder each evening, when the clerk comptroller and the clerk of the kitchen, together with the larder staff, attended ‘the coupage of the fleyshe … in the grete larder, as requiryth nyghtly to knowe the proportion of beef and moton for the expences of the next day, and see the fees thereof, to be justly smytten by the yeoman cooke’.

4

The larder officers, like the acatery officers just mentioned, took their ‘fees’ in the form of joints cut off the ends of the carcases. The sergeant had the two joints of each ox cut from just above the rump, the two top neck joints with the ‘bore of the head’, the feet, the belly piece and the hindquarters ‘to the arse bone’, while the yeomen

had the forelegs struck off at the first joint, and a piece of the first joint of the neck.

5

The yeomen also took three joints of the scragend of the necks of sheep and veal calves, along with their rumps and the lower parts of their back legs, while the grooms had the head, feet and small end of the chine, or lower back joint, of every hog. The main parts of the carcases, complete with ribs, breasts, shoulders, loins and hindquarters, would then be cut into portions, each sufficient to serve a certain number of messes ‘according to the ancient custome’

6

Each ox, which would weigh some 500lb (227kg), was cut up into major joints that would provide the following messes: