Alien Universe (31 page)

Authors: Don Lincoln

Another poorly known factor is the fraction of planets that develop life that go on to evolve intelligent life (

f

i

). There are two very distinct ways to think about this. The first school of thought suggests that the development of intelligence is inevitable. Proponents point to the observation of a steady increase in the intelligence of species over the course of the eons. Under this way of thinking, the formation of intelligence is approximately inevitable, given enough time. A contrasting way of thinking points to the fact that there have been millions of vertebrate species, and only humans have developed the kind of intelligence we have. If something had caused the hominid line to go extinct 100,000 years ago, there is no indication that another species would have gained intelligence in the intervening time. Another factoid is that, even though dinosaurs ruled the planet for about 150 million years, there is no evidence of significant intelligence developing during that time. This suggests that the development of intelligence is rather rare.

The fraction of intelligent and technologically advanced civilizations that will announce their presence (

f

c

) would seem to be rather high. We have only us to use as an example. We rarely intentionally attempt to communicate with potential civilizations around adjacent stars, but we don’t have to do this intentionally. After all, since the early days of the twentieth century, mankind has been broadcasting its existence into the cosmos.

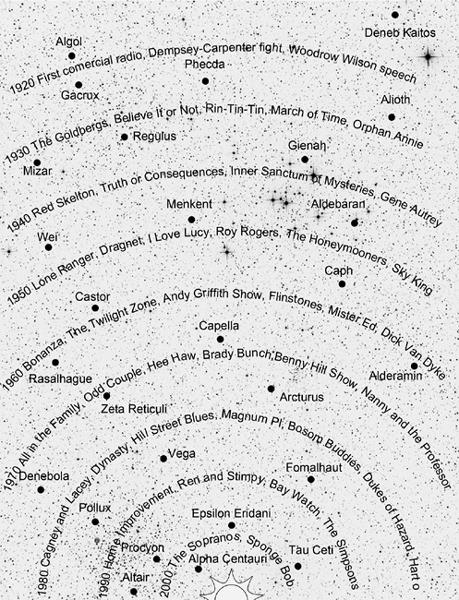

Figure 7.1

shows us the radio and television bubble surrounding the Earth as of 2010.

The final factor, which is the lifetime that a civilization will emit a detectable signal (

L

) is also not well known. Civilizations on Earth tend to be at their peak for several hundred years, but subsequent civilizations often use technology from the antecedent civilization. Further, we don’t know for how long we will use radio and broadcast television to communicate. However, unless war decimates human life on Earth, either from atomic cataclysm, extreme and rapid environmental devastation or some sort of intentional biological warfare, it seems probable that ongoing use of radio, television, or some sort of electromagnetic emission is likely to continue for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

Given the difficulty inherent in determining the parameters that go into the Drake equation (and even whether the equation is an appropriate mathematical representation of the question), it is inevitable that there will be ongoing uncertainty as to the number of technologically advanced civilizations we expect in our galaxy. Drake’s equation clearly assumes that the civilizations are independent, with no cross-pollination. It also doesn’t allow for a civilization that spans a large segment of the galaxy. A dispersed civilization might allow for bits and pieces of the society to go extinct, but it is more difficult to believe a thriving culture spanning millions of star systems would disappear entirely.

FIGURE 7.1

.

Nearby stars have been graced by our radio and television signals for nearly a century. It is easy to imagine that our first contact with Aliens will not be intentional but rather by an extraterrestrial civilization intercepting reruns of

Ren and Stimpy

. It’s kind of a sobering thought.

Kardashev Scale

In 1964, Nikolai Kardashev formalized the idea of variations in the level of technological achievement of extraterrestrial civilizations. He defined three distinct classes.

Level I: A civilization that can totally utilize all the energy from a star that reaches a planet

Level II: A civilization that can totally utilize the energy resources of a star

Level III: A civilization that can totally utilize the energy resources of an entire galaxy

Subsequent extensions of Level IV (utilizing the energy output of the visible universe) and Level V (utilizing the energy of the multiverse) are later modifications and rarely used.

It is perhaps obvious that a Level III civilization will be more detectable than a Level I civilization, in the same way that a spotlight is easier to view from great distances than a candle. As we read further into the searches for extraterrestrial life, we must keep in mind the fact that when we look beyond our solar system, we’re not necessarily looking for life with the same technological level as our own. It is quite possible that an extraterrestrial civilization might have a significant head start on us. To a degree, the current technological phase (i.e., the phase in which both electricity and radio have been mastered) of our civilization is only about 100 years old. Imagine the kinds of technology we might master by the year 3,000. Just a mere millennia is likely to bring us unfathomable advances. Now imagine that a civilization in our stellar neighborhood hit our level of technological development when the Neanderthals were dying out, when a lineage of Miocene ape experienced the mutations that lead to

Homo sapiens

, or even when the impact at Chicxulub killed the dinosaurs. Those Aliens would presumably have mastered technologies of which we can only dream (or, more likely, beyond anything we can dream of). Given the raw numbers of stars out there and working under the assumption that the Earth is not an exceptional planet, it seems inevitable

that any intelligent extraterrestrial species we encounter will be more technologically advanced than us. So, what do we see?

The Big Ear

The thought of using radio to listen for life on other planets is an old one that can be traced back at least as far as Nikola Tesla. In Colorado Springs in 1899, he believed that he had perhaps established communication with extraterrestrials, although he was uncertain whether it was from Mars or Venus. (Keep in mind that this was at the height of the media frenzy about the question of canals on Mars.) He received in his equipment groups of clicks of one, two, three, or four. This was reminiscent of how the Martians communicated in the 1952 movie

The Red Planet Mars

(discussed in

chapter 3

). He wrote of the experience in the February 19, 1901, issue of

Collier’s Weekly

(as well as many other places; Tesla was both a technical genius and a prolific popularizer). He said, “There would be no insurmountable obstacle in constructing a machine capable of conveying a message to Mars, nor would there be any great difficulty in recording signals transmitted to us by the inhabitants of that planet.” His work in this area has long since been discredited, with many suggested explanations, the most likely of which is that he simply didn’t understand his equipment. This isn’t incredibly surprising, as Tesla’s pronouncements were often more spectacular than his accomplishments, and his accomplishments were very spectacular indeed. The most important point is that the idea of using radio to communicate to other planets has its antecedents in the very beginnings of mankind’s use of the technology.

Although Tesla’s efforts were perhaps the first, he was not alone. About two decades later, Guglielmo Marconi made similar claims. Marconi and Tesla were favorites of the media (think Steve Jobs in an era where this kind of technological innovation was rare) and received substantial attention in the press. In 1919, Marconi believed it possible that he received radio broadcasts from beyond the Earth. His evidence included simultaneous reception of signals in New York and in London, suggesting that the source was not local. Critics pointed out that radio receivers at the Eiffel Tower and in Washington, D.C., heard nothing. The

New York Times

had multi-week coverage of the story, often on the first page and above the fold. The editors of the

New York Times

suggested that perhaps it would be better if mankind did not contact life on other planets. Their reasoning was that the other life, being older and thus more advanced, would have technology far beyond ours and that mankind was not ready for it. This caution was seconded much later in the twentieth

century by physicist Stephen Hawking, who pointed out that when an advanced culture encountered a less advanced one, the less advanced culture invariably suffered. This is another reason to think it wise to “lay low.” In retrospect, both Marconi and Tesla were monitoring frequencies that were too low to penetrate the Earth’s ionosphere, but they were still efforts that electrified the public.

The periodical

Scientific American

was just as cutting edge a magazine in 1919 as it is today and, within a couple of weeks, they had penned an article on Marconi’s claims, followed a couple of months later by a truly forward-thinking article. Marconi was talking about having received an occasional letter of Morse code, and

Scientific American

pointed out the inherent difficulties of using such a code for interplanetary communication. They went so far as to advance a way to communicate with Mars that might work, anticipating by decades a similar message broadcast from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico. In this much later attempt, mankind intentionally beamed a signal into space with the hopes that it might one day be intercepted by extraterrestrials.

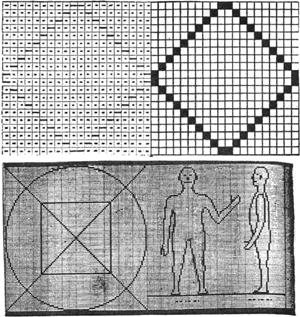

Scientific American’s

1920 proposed message is shown in

figure 7.2

.

While the belief in Martian canals had disappeared among most scientists with the 1909 Martian opposition, the idea lived on in the public imagination for much longer. During the 1924 Martian opposition, in which Mars and Earth were particularly close, another attempt was made to search for radio signals from our neighbor planet. On August 21 to 23 (the date of the opposition), the United States declared a “National Radio Silence Day,” which was somewhat misnamed. What was actually advocated was that all radio traffic was turned off for five minutes, every hour, on the hour, over a 36 hour period. During that time, receivers were to listen to the heavens, looking for that Martian signal. The U.S. government got into the act with the chief signal officer of the army telling his radio stations to be vigilant for unusual transmissions, while the secretary of the navy directed the most powerful radio stations under his command to broadcast minimally and keep an ear out. Very few of the commercial stations complied, except one in Washington, D.C. The attempt was a dismal failure, scientifically speaking, but it was an interesting idea.

Over the course of the next few decades, the idea of interplanetary communication persisted among a few, including amateur radio operators. The simple fact was that the technology of the era was not really up to the project. Further, after 1930 or so, the scientific community had essentially dismissed the possibility of intelligent life on Mars, which meant the new goal was interstellar communication. This capability was definitely beyond the capability of the equipment of the time.

FIGURE 7.2

.

This figure from the March 20, 1920, issue

of Scientific American

shows an early attempt to design a message that would be understandable by an extraterrestrial civilization. It is hard enough for an English-only speaker to write a message that would be understood by (say) a literate person who reads only Chinese, let alone a culture that is as different from humanity as an Alien civilization is likely to be.

Scientific American

.

In the 1950s, the field of radio astronomy was born. Astronomers knew that astronomical bodies would emit electromagnetic radiation beyond the visible spectrum. Large radio dishes began to be built to study things like the galactic center, the sun, and similar sources. And this is where we again meet Frank Drake (of the Drake equation).

Frank Drake was a radio astronomer working to build the new 140 foot radio telescope in Green Bank, West Virginia. This huge antenna was housed at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) and signaled that a national decision had been made on whether it was better for a country to fund a large, central government laboratory or many, smaller research efforts, dispersed across the various universities and where individual researchers could exercise greater control over their research interests. Big won.