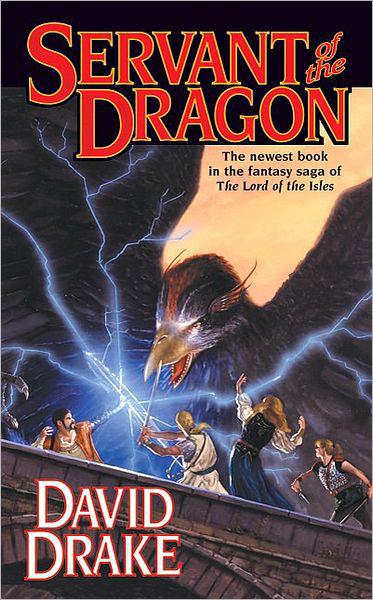

Servant of the Dragon

SERVANT OF THE DRAGON

by David Drake

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this novel are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.

SERVANT OF THE DRAGON

Copyright 1999 by David Drake

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, Inc.

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Tor Books on the World Wide Web:

http://www.tor.com

Tor is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, Inc.

First Edition: August 1999

ISBN 0-8125-6494-4

Printed in the United States of America

To Jamuna devi dasi, AKA Melissa Michael

Who makes the world a better place

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dan Breen, my first reader, describes himself as a clerk. This is valid; but while I value the way he catches grammatical errors, I gain even greater benefit from his more general criticisms. Though I often disagree (though I most often disagree), he forces me to consider why I did the particular things that I did.

My mean time between failure with computers is about six months. Losing three of them during the writing of this novel was pretty remarkable, though. My thanks to Mark L Van Name, Allyn Vogel, Ruben Fernandez, and Rich Creal whose help made a series of frustrating experiences nonetheless survivable.

If there's an author photo on this book, it's probably the one John Coker took in 1986 (I'm grayer but I wear the same trouser size). John is not only a fine photographer, he's one of the nicest people you could ever hope to meet. I really appreciate his permission to use his picture.

Things go wrong in publishing, just as they do in every other form of human endeavor. Stephanie Lane at Tor works hard to fix errors. This is no more common in publishing than it is anywhere else, so I feel very fortunate to work with her.

I had a difficult time during the course of writing this book. (See the first paragraph above for a lot of the reason.) My friends and especially my wife Jo were unfailingly supportive. My sincere thanks to all of them.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

The (common) religion of the Isles is based on Sumerian cult and ritual, but the magic itself comes from the Mediterranean and is mostly Egyptian in its original source. The

voces mysticae

which I've referred to as 'words of power' in the text represent the language of demiurges; that is, they are intended to have meaning to beings which can then translate human desires to the ultimate powers of the cosmos. I have copied them from real spell manuscripts of the classical period.

I don't personally believe that the

voces mysticae

have power over events, but millions of intelligent, civilized people

did

believe that. I don't pronounce the

voces mysticae

aloud when I'm writing.

Rather than invent literary sources for the background of

Servant of the Dragon

, I've used real ones. The actual quotes are from poems by Horace and Ovid; my translations are serviceable, but Horace in particular deserves better than anyone can give him in English.

In addition there are passing references to Homer, Vergil, Hesiod, Athenaeus, and Plato. The fascinating thing about going to original sources is that it's the best way to learn not only what people distant in time thought but also how they went about thinking.

And you know, when you've seen the differences between us and the ancestors of our western culture, it may make you—as it certainly has made me—a little more tolerant of the beliefs of different modern cultures. That wouldn't be a bad thing for the world.

—Dave Drake

Chatham County, NC

PROLOGUE

The deeps trembled, shaking a belfry which hadn't moved for a thousand years. Eels with glassy flesh and huge, staring eyes twisted, touched by fear of the power focused on the sunken island. Cold light pulsed across their slender bodies.

A bell rang, sending its note over the sunken city. It had been cast from the bronze rams of warships captured by the first Duke of Yole. A tripod fish lifted its long pelvic fins from the bottom and swam off with stiff sweeps of its tail.

Ammonites, the Great Ones of the Deep, swam slowly toward the sound. They had tentacles like cuttlefish and shells coiled like rams' horns. The largest of them were the size of a ship.

The powers supporting the cosmos shifted, sending shudders through a city which nothing had touched for a millennium. The bell rang a furious tocsin over Yole.

The island was rising.

The Great Ones' tentacles waved like forests of serpents in time with words agitating the sea. In daylight their curled shells would shimmer with all the colors of the sun. Here the only light was the distant shimmer of a viperfish flashing in terror as it fled.

The dead lay in the streets, sprawled as they had fallen. Over them were scattered roof tiles and the rubble of walls which collapsed as the city sank. Onrushing water had choked their screams, and their outstretched arms clutched for a salvation which had eluded them.

The bodies had not decayed: these cold depths were as hostile to the minute agents of corruption as they were to humans. Some corpses had been savaged by great-fanged seawolves which had swept into the city on the crest of the engulfing wave; other victims had been pulled into the beaks of the Great Ones and there devoured. For the most part, though, the corpses were whole except where sluggish, long-legged crabs had picked at them.

Tides of light touched the drowned buildings and gave them color. Faint tinges of blue brightened as the island rose. At last even the rooftiles regained their ruddy tinge.

The Great Ones swam slowly upward, accompanying Yole its return. The movements of their tentacles that twisted the cosmos.

The belfry of the Duke's palace, the highest edifice in Yole, broke surface. Water cascaded from stones darkened by the slime which crawled along the sea's deepest trenches.

Moments later the Great Ones surfaced, their shells a shimmering iridescence in the dawnlight. They swam slowly outward so as not to be trapped by the rising land. The Sshaped pupils of their eyes stared unwinking at the circle of wizards who stood in the air above the rising city.

Three of the wizards wore black robes with high-peaked cowls over their heads. Their faces and bare hands were blackened with a pigment of soot and tallow. Only their teeth showed white as they chanted words of power:

"Lemos agrule euros . . ."

Three wizards were in robes of bleached wool, white in shadow and a mixture of rose-pink and magenta where the low sun colored the fabric. They had smeared their skin with white lead so that their eyes were dark pits in the thastly pallor of their faces.

"Ptolos xenos gaiea . . ."

the wizards chanted.

The earth rumbled. Torrents thundered from the doorways and windows of Yole, spilling in echoing gouts along the broad streets that led to the harbor. Corpses flopped and twisted in the foaming water. Each syllable could be heard over the chaos, though the words came from human throats.

The wizards' leader was black on his left side, white on the right. He chanted the words of power which his fellows echoed, syllable by syllable. From the brazier standing before him, strands of black smoke and white smoke rose, interweaving but remaining discrete.

"Kata pheinra thenai...."

Facing the leader was a mummified figure whose head the wizards had unbandaged. The mummy's sere brown skin bore the pattern of tiny scales, and the dried lips were thin and reptilian. Its tongue, shrunken to a forked string, flickered as the figure chanted. Words of power came from its dead throat.

The belfry continued to shudder, but the bell's voice was lost in the greater cataclysm. Sea birds wheeled in the air, summoned from afar as the sea thundered away from the newly risen land.

"Kata, cheiro, iofide...,"

chanted the wizards.

The ghost of a pierced screen hung in the air beyond the wizards, a filigree of stone that wavered in and out of focus. The screen's reality was that of another time and place, but the incantation had drawn it partway with the wizards.

The soil of Yole touched the wizards' feet. The island gave a further convulsive shudder, then ceased to rise. Waves, shaken away by Yole's reappearance, returned to slap its shore in a fury that slowly beat itself quiescent.

In the harbor the Great Ones floated. Their tentacles waved in a ghastly parody of a dance.

Gulls and frigate birds dived and rose again in shrieking delight. Yole's rise had swept creatures of the deep to the surface faster than their bodies could respond to the changes in pressure. Birds carried away the ruptured carcases in their beaks.

The six lesser wizards collapsed on the dripping cobblestones of a plaza, gasping in exhaustion from the weight of the spell they had executed. Their leader raised his arms high and shouted,

"Theeto worshe acheleou!"

Momentary silence smothered the world, stilling the waves and even the screams of the gulls. Sunlight winked on the armor of soldiers and the jewelry of ladies who had arrayed themselves in their finest, not knowing that they were dressing for their own deaths. A child's hand still clutched an ivory rattle; it too gleamed in the sun.

The leading wizard remained standing. His mad peals of laughter rang across the dead city.

The mummy stood also, motionless now and silent. Its sunken eyes were on the wizard, and its reptilian features were twisted into a mask of fury.

CHAPTER ONE

Prince Garric of Haft, Heir Presumptive of Valence III, King of the Isles—and already by any real measure the ruler of the kingdom—facced his Council of Advisors. Down the table from him were the chief nobles of the island of Ornifal; some of the most powerful men in all the Isles. They were waiting for him to make known his wishes on the point before the council.

Garric's wishes were to be back home in Barca's Hamlet, the village on Haft where he'd been raised for all but the first days of his eighteen years. There he'd been Garric or-Reise, the innkeeper's son; a clever lad and a strong one, a boy you could trust to keep your sheep from getting into trouble even though he was likely to be reading a book while he watched them. Life was a lot simpler then, although it had seemed complicated enough at the time.

"You can't go back, lad," whispered the ghost in Garric's mind: Carus, the last king of the united Isles, whom wizardry had drowned a thousand years before. "Even if duty didn't keep you here in Valles, Barca's Hamlet isn't really your home any more."

"I appreciate the desirability of a united command, Waldron," Garric said wearily. He didn't need King Carus, his ancient ancestor, to explain that Garric had seen too much of the world already to fit back into the comfortable round of a peasant community. "Nonetheless I'm not willing at least at this point to make the fleet a division of the Royal Army."

And thereby put the fleet under Lord Waldron, the commander of the Royal Army. Waldron was a tall man, well into his sixties, who wore his iron-gray hair cropped close to fit under a helmet. His lineage went back over a thousand years, and he could raise several hundred men-at-arms from his family estates in the north of Ornifal.

In a world constituted the way Lord Waldron believed it should be, Waldron himself would be King of the Isles. Garric kept his face straight, but he managed a wry inward smile which the image of King Carus in his mind shared. That Waldron served him, Garric or-Reise, was proof as clear as anyone could ask that Garric belonged in the position he now held.

However much Garric and Waldron both hated the fact.

"The existing naval officers are completely untrustworthy," said Lord Attaper, "and the oarsmen aren't much better. They rebelled against King Valence and the few who survived will rebel against you too if they get the chance."

Attaper was Waldron's junior by twenty years. Both men were nobles—all those in this room were noble, with the exception of Garric himself—but Attaper had inherited a title without wealth. He'd entered the Blood Eagles, the royal bodyguard, and had risen to their command by the time a cataclysm brought Garric to the throne in all but name. Attaper was loyal to the oath he'd sworn to King Valence; but he was an ambitious man, and a very hard one.

"Let me expand the scheme of training pikemen who can also row the warships," he continued. The scheme was Garric's own. He'd copied the phalanx with which King Carus had won every battle he fought—except for the last one against wizardry and the sea. "You'll have an army you can count on and you'll be able to shift in a week or less to any island in the kingdom."

"May I remind both of you gentlemen that soldiers have to be paid!" said Lord Tadai, now Royal Treasurer in place of a well-meaning incompetent who'd held the position under Valence. Tadai wiped his round face with a handkerchief embroidered with the arms of his house, the bor-Tadimans.

The council meeting was a formal occasion which required court robes of thick brocade. Tadai was a heavy man, and all his enormous wealth couldn't keep him from sweating like a pig. "Armies are a luxury, and—"

"A luxury!" Waldron exploded, rising from his seat. The old warrior's hand twitched in the direction of his sword.

"Did a trained army seem such a luxury a month ago when you expected the Queen's forces to swarm down on Valles, Lord Tadai?" Attaper snapped, more controlled than Waldron but no less angry.

They were all getting to their feet and shouting. Royhas bor-Bolliman, Garric's Chancellor and closest to being Garric's friend of the men present, snarled, "And speaking of money, Tadai, the honor of the kingdom is being tarnished by your failure to pay—"

"Gentlemen," Garric said in a mild voice. He knew no one would listen to him, but his father had raised him to be polite.

Carus nodded approvingly in his mind. Garric remembered—though the memories weren't his own—a score of arguments, some of them outright brawls taking place while Carus stood grimfaced and aloof, waiting to choose his time to intervene so that he wouldn't become part of what he wa trying to halt.

Liane bos-Benliman, a dark-haired girl of Garric's age, sat beside Garric and a half-step back, making it clear that she had no right to speak during the deliberations. In this room she was acting as Garric's secretary. She met Garric's eye and smiled, but there was concern in her expression.

Liane was the only living person present who wanted the things Garric wanted and no more: peace and unity for the Kingdom of the Isles, which wizardry hda shattered a thousand years before and which wizardry now threatened to crush to dust. In Garric's eyes Liane was the loveliest woman in the Isles, and a more neutral judge might have concurred.

Liane knew that Garric had had less than an hour's sleep the night before—a spy had arrived from Sandrakkan with information about the Earl's intentions that couldn't wait—so she worried about him. In her lap was a notebook whose leaves were thin sheets of limewood, waxed on either side and bound with silk cords. She made notes with a blunt stylus, using a form of commercial shorthand. Liane's father, Benlo bor-Benliman, had been a wealthy merchant who travelled extensively.

Benlo had been a wizard as well. That had cost him first his fortune, then his life; and in the end, he had lost his very soul. Liane had faced demons and her father's demonic will. She hadn't flinched from any of that, and Garric didn't expect she ever would flinch.

"The money's there, you just won't release it as your duty demands!" Royhas cried, leaning over the table from his side. Tadai, leaning toward the chancellor with his face the color of his scarlet handkerchief, said, "If you're so set on finding jobs for all your relatives, Royhas, then I suggest you find the money for them as well!"

Lord Sourous was complaining that a friend—"A friend as close as my life, I'll have you know!"—hadn't gotten the post he rightly expected. Lord Pitre was demanding justice, by which he meant vengeance against those who had treated him as a fool and a toady in the last years of King Valence's unassisted reign....

Garric's index finger touched the conference table. It was of burl walnut, polished to a glassy sheen that brought out the richly complex pattern of the grain. In Barca's Hamlet men shaped wood with an adze or a broad-axe. Garric had never seen a saw or a sawn plank until fate took him from his home. A table like this was fit for the Queen of Heaven and Her consort, not mortals like Garric or-Reise.

"And besides that—" Royhas said.

Garric slammed his fist down. The table, large enough to seat twelve and heavy in proportion, jumped on the stone floor.

No one spoke for a moment. Waldron took his hand from his swordhilt and smiled faintly.

Garric smiled back. He hadn't eaten since... well, he'd had an orange and a roll baked from wheat flour at dawn, with nothing since. Maybe that was why he felt queasy.

"Gentlemen," he said, "I'm going to adjourn this meeting because I'm obviously not in condition to keep it under control."

"I'm sorry, your highness, but—"

"I didn't mean to—"

"Of course, Garric, I'll—"

"Well, really, Pr—"

"Silence!" Garric bellowed. The conference room shutters were slatted to let in summer breezes while maintaining privacy from the eyes of folk wandering through the palace grounds. They rattled against their casements. Even Liane jumped, though she immediately grinned as well.

"Gentlemen," Garric continued in the quiet tone he preferred. "We'll resume this meeting tomorrow in the third hour of the afternoon. I know that some of you have written proposals. Leave them with Liane and I'll review them before that time."

Garric's eyes flicked from Royhas to Tadai. Both men had their mouths open to speak. They saw Garric's expression, as grim and certain as a swordedge.

"Quite so," the chancellor murmured as he took from his wallet a scroll of parchment bound with a red ribbon. He handed it to Liane with a courtly flourish.

Lord Tadai had a similar document, though his ribbon was pale yellow, dyed with the pollen washed from beehives. "There's an annexe which one of my aides will bring you shortly, Lady Liane," he said in an undertone.

The conference room was one of the many separate buildings in the grounds of the royal palace in Valles. The councillors passed out one by one to meet their aides and bodyguards, the latter carrying ivory batons instead of swords. Only the Blood Eagles and folk the king particularly wanted to honor were permitted to go armed within the palace grounds.

Garric grinned wryly. Lord Waldron had never gotten quite so angry that he drew his sword in a council meeting, but Garric and the others would have been a lot happier if he were disarmed. Waldron himself might have preferred a legitimate excuse that would keep his hot temper from causing him trouble: the army commander was a choleric man, but by no means a stupid one.

There was no choice, though. Lord Attaper carried a sword by virtue of his office as commander of the Blood Eagles. Lord Waldron's pride wouldn't permit him to be disarmed in the presence of his rival for military influence.

"The people who think a king gives orders and things are done," Carus said across a thousand years, "have never been king, lad."

"Well, I've already submitted a petition!" Lord Sourous said. Because Garric considered Sourous to be insignificant—the young noble had his place on the council because he was head of an ancient, wealthy family and had been one of the plotters who brought Garric to his present position—he hadn't expected further argument from that quarter. Sourous couldn't possibly be as stupid as he sometimes seemed... but he certainly managed to act like he was a moron on occasion.

This was apparently one of those occasions.

"Lord Sourous, the prince has personally reviewed your request that Lord Hastern bor-Hallial be given a district governorship, preferably in the north of Ornifal," Liane said unexpectedly. Her tone was dryly pleaasnt. As she spoke, she opened the folding travel desk in which she kept current documents.

Other councillors paused to listen. Sourous gaped at him like a carp lifted on the springy tines of a fish spear.

"Lord Hastern ran through his patrimony in the first nine months after his father's death," Liane continued. "At the end he beggared his mother also, by forging her signature and seal to a pledge of the dower portion of the estate. Since then he's been borrowing on the strength of his name and living on the bounty of women."

Liane's father had used Serian bankers. Liane used those connections to get her information. TheSerians were culturally distinct from the Isles' other ethnic groups, so their assessments of a man like Lord Hastern were detached in a fashion that the opinions of other Ornifal nobles could not be.

"Lord Hastern has pretty completely emptied his name of value," Liane went on sweetly, "but there appears to be a sufficiency of foolish women to keep him afloat for months and perhaps years to come. He is getting a little long in the tooth, though."

"I, ah...," Sourous said. He would have fled, but Garric's glare transfixed him.

"So as you see, Lord Sourous," Garric broke in, "I gave your friend quite careful consideration before I decided whether he was a proper guardian for the revenues of a district. Do you have anything further to add?"

"No, no," Sourous said. Garric bowed in dismissal; Sourous slipped out the door.

The last councillors remaining were Attaper and Waldron. The two warriors stepped to the doorway together and halted. After a moment Attaper grinned tightly. "I trust you not to stab anyone in the back, Lord Waldron," he said. "Even me." He swept through the door ahead of the older man.

"Puppy!" Waldron muttered as he strode out in turn. He left the door open behind him: opening and closing doors was beneath the concern of a man of Waldron's lineage.

A servant peered into the conference room to see what those still within might wish. Liane shook her head minusculy and closed the door herself.

"It was perfect!" Garric said with a grin. "I almost broke out laughing when you cited Sourous chapter and verse about the worthless parasite he thinks is his friend. Ilna couldn't have done it better!"

Garric thought about the friends he'd grown up with: his sister Sharina, tall, blond, and (like Garric himself) able both to read the classics and to put in a full day's work at their father's rural inn; Cashel or-Kenset, an orphan since his father's early death, almost as tall as Garric and as strong as any two other men—

And Cashel's twin sister Ilna: dark-haired, pretty; a weaver whose skill passed beyond art to wizardry. Ilna's tongue was as sharp as the bone-cased knife she kept for household tasks and to cut the selvage of her fabric. Ilna might well have dressed Sourous down in that fashion, but—

"Ilna would've enjoyed it," Garric said sadly. "I enjoyed it while it was happening, but I shouldn't have. Sourous is a fool, but that's not a crime. I liked to see him squirm because I'm tired and frustrated."