AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War (12 page)

Read AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War Online

Authors: Larry Kahaner

BOOK: AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War

7.27Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Just after the U.S. invasion, American GIs began reporting up the chain of command a disturbing trend. Children, some as young as twelve years old, were seen carrying AKs. Rebel armies discovered that this light, easy-to-use weapon, which required less than an hour of training time, was perfectly suited for small hands and bodies. Even youngsters with poor coordination or strength could be turned into a lethal killers. The AKs required almost no maintenance or cleaning, so absentminded kids did not have to worry about forgetting to take care of their weapon. Poorly funded groups had no qualms about distributing AKs to children; if they lost the weapon or died in battle, the economic loss would be small.

None of this was known to thirty-one-year-old Green Beret sergeant first class Nathan Ross Chapman of San Antonio, Texas. On January 4, 2002, he became the first American soldier to be killed by hostile fire in Afghanistan. His unit was coordinating missions with friendly tribes in Paktria Province near Pakistan when they were ambushed.

The shooter was a fourteen-year-old Afghan boy, born and nurtured in the Kalashnikov Culture and armed with an AK. Although facing child soldiers barely strong enough to hold an AK may have been a new and shocking experience for young GIs in Afghanistan, it had been a widespread and accepted practice in Africa for decades.

4

THE AFRICAN CREDIT CARD

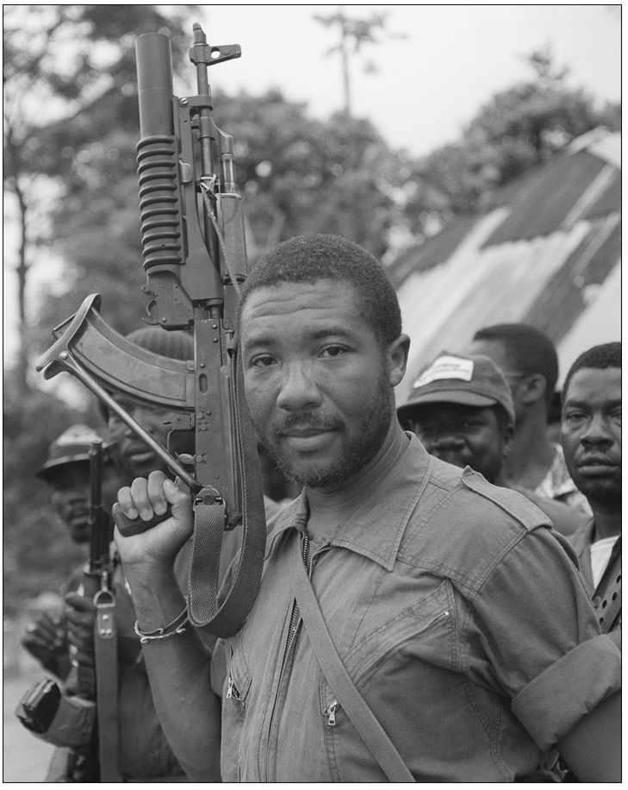

ON CHRISTMAS EVE 1989, forty-one-year-old Charles Taylor, a former security guard, gas station mechanic, and truck driver, invaded the African nation of Liberia with a ragtag group of about one hundred rebels primarily armed with cheap AKs. Crossing the border from Ivory Coast, Taylor and his men first waged guerrilla warfare in the heavily forested Nimba County, securing town after town as they added soldiers to their force.

With the Soviet bloc countries selling AKs for quick cash, Taylor, with reported support from Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gadhafi, was able to arm his poorly trained and outfitted rebels for little money. At the same time, Western nations paid almost no attention to small-arms trade in Africa. They were still focused on weapons of mass destruction and believed light weapons, those that could be carried by soldiers, were of little consequence.

Throughout Africa, the disappearance of superpower support in the late 1980s led to the collapse of traditional government militaries. Countries fragmented into tribal groups that harbored long-standing ethnic resentments. The demand for small arms grew and prices dropped dramatically because of the deluge of available arms from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Eastern Europe. Although cheap AKs were not responsible for the beginning of brutal, decades-long conflicts in Africa, they were a principal factor in prolonging them. The weapons brought devastating changes to a frail continent fraught with disease, hunger, and few economic opportunities.

Adding to the problem was the lack of desire among Western nations to track arms. Even if they were interested, tracking became impossible due to the sheer volume of weapons flooding world markets. United Nations officials were unable to garner support for programs to monitor small arms or limit their sale. In fact, it was never illegal to sell arms to Africa except in later instances of UN-IMPOSED arms sanctions, which were largely ineffective anyway.

“A few planeloads of arms going to an African country just didn’t make the cut, in terms of an issue governments would want to pay attention to,” Tom Ofcansky, an African affairs analyst with the State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research, told PBS’s

Frontline

in 2002. “But the impact of a few planeloads of arms, as we’ve seen repeatedly in Africa, had a devastating impact on fragile African societies.”

Frontline

in 2002. “But the impact of a few planeloads of arms, as we’ve seen repeatedly in Africa, had a devastating impact on fragile African societies.”

Charles Taylor didn’t know it at the time, but he was on the cutting edge of a trend that would result by 2000 in the deaths of seven to eight million Africans as well as the displacement of millions of people seeking refuge from prolonged, low-level conflicts fueled by cheap and indestructible AKs.

Like the mujahideen in Afghanistan, Taylor employed his small-arms firepower to ambush government forces. Systematically, he and his National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), isolated unprotected towns instead of fighting government forces head-on as he pushed south toward the capital, Monrovia, over the weeks and months following his Christmas Eve invasion. His group also took over key industrial facilities such as the country’s second largest rubber plantation in the southern port of Buchanan.

In 1989, Charles Taylor and a ragtag group of a hundred men armed mainly with AKs stormed the presidential palace in Liberia and controlled the country for the next six years. By issuing AKs to anyone who swore allegiance to him, Taylor stayed in power with bands of thug soldiers who were allowed to pillage their defeated enemies as payment for their loyalty.

Pascal Guyot/AFP/Getty Images

Pascal Guyot/AFP/Getty Images

Taylor garnered troops by exploiting their tribal allegiances and anger at the current government for poor economic conditions. This tribal anger stemmed from the modern beginnings of Liberia, when freed American slaves established a colony there in 1822. By 1847, these Americo-Liberians, as they were called, declared independent the Republic of Liberia, and named its capital Monrovia for President James Monroe. The second largest city, Buchanan, was named for President James Buchanan’s brother Thomas, who later became vice president of Liberia. Buchanan was honored for hand-delivering the new Liberian constitution to the United States after it was written by Harvard University professor Simon Greenleaf. It was this document that sowed the seeds for Liberia’s ensuing conflicts, because it denied rights to those other than the freed American slaves, the Americo-Liberians. The natives, the overwhelming majority, were considered second-class citizens, and the Americo-Liberians controlled the country’s government and financial and industrial infrastructure.

Efforts over the years by various presidents to bring tribal Africans into the economic and political fold failed, and the majority of the population considered the government as corrupt. This was exacerbated by generous concessions to U.S.-owned firms like the Firestone Plantation Company, which exerted great influence on the country’s internal politics, to the resentment of many Liberians.

Descended from Americo-Liberians on his father’s side and the indigenous Gola tribe on his mother’s, Liberian-born Taylor was fascinated by the history of his country and its relationship with the United States. In 1972, he emigrated to the United States, where he graduated in 1977 with a bachelor of arts degree in economics from Bentley College near Boston. While in college, he became the national chairman of the Union of Liberian Associations in the Americas, a group founded in 1974 “to advance the just causes of Liberians and Liberia at home and abroad.” While he chaired the group, Taylor politically matured, even forming a protest demonstration against then Liberian president William Tolbert in 1979 when the leader visited the United States.

Instead of ignoring Taylor, Tolbert debated him, and by some accounts he lost the verbal joust. Taylor was arrested when he declared that he would take over the Liberian mission, but was later released when Tolbert refused to press charges. In fact, Tolbert invited Taylor to return home to Liberia, and in 1980 he did.

On April 12, 1980, army sergeant Samuel K. Doe killed Tolbert during a military coup. Doe, the first indigenous Liberian to became president, and a member of the Krahn tribe, ruled the country with an iron fist. He tortured and killed Americo-Liberians in a reign of revenge.

From here, Taylor’s story took some weird turns. Despite his connection with the previous government, Doe hired him as the government’s head purchasing agent, but he was thrown out in 1983, accused of embezzling more than $900,000. Taylor fled to the United States and was arrested in Boston at the request of Doe and held for extradition. After languishing for almost a year in the Plymouth County House of Corrections, Taylor in 1985 escaped by sawing through bars and climbing down a bedsheet rope. He made his way back to Africa. American officials suspected that he spent the next four years in Libya with Gadhafi before invading Liberia with his AK-armed insurgents.

While Taylor’s ultimate goal was the destructive overthrow of the corrupt Doe government, he accomplished more than that. He created a watershed event in warfare history, revealing that the accepted model for modern warfare had changed. In the past, war had been conducted as a series of armed conflicts between armies of established countries. The goal was to gain territory or force an ideology. With Taylor, the world saw a different kind of warfare emerge. It consisted of paramilitary combatants, armed with light, cheap weapons, whose long-term goal was not only to topple a government but to attack civilians en masse along the way. These soldiers were permitted, even encouraged, to engage in any atrocity, including rape and ethnic slaughter, to terrorize the population and gain control. Civilians were fair game, including children, which was a major change from previous contemporary wars in which combatants had tried to limit “collateral” damage. Even in the case of the German bombing of London or the U.S. dropping of atomic bombs on Japan, the goal was capitulation; once an enemy surrendered the conflict was considered over.

Not so with Taylor. He wanted money and power in addition to political command. He cleverly recruited fighters by encouraging their tribal hatred and giving them cheap automatic weapons. In return they could plunder from those they killed. They could loot, pillage, and arrest anyone they wanted and murder them if they chose. In this way, Taylor could build an army, and his only expense was an AK for each recruit at a cost of less than fifty dollars each, in some cases as low as ten dollars.

Taylor went further by putting large numbers of weapons in the hands of youngsters, many of them war orphans, who had few alternatives for sustenance and shelter in a country already ravaged by strife. Seeing gangs of boys with AKs slung over their shoulders, sporting baseball caps and ripped T-shirts, terrorizing jungle villages, Western observers likened it to the book

Lord of the Flies

, the classic William Golding novel of brutal boys running wild, lawless gangs playing out their sadistic fantasies.

Lord of the Flies

, the classic William Golding novel of brutal boys running wild, lawless gangs playing out their sadistic fantasies.

Taylor’s Small Boy Units, as he dubbed them, often were put in charge of makeshift checkpoints where they stood menacingly, AKs at the ready, demanding bribes for passage. Other times they were let loose in villages that stood in the way of Taylor’s march toward the capital, Monrovia. These naive youngsters were promised cars, toys, even computers for their service. Outsiders found the contradictions unsettling, as one minute these boys would act tough as combat veterans and in the next they would play with their toys and games. “I met and spoke with young child soldiers in Danane, Ivory Coast. They had crossed the border from fighting in Liberia and acted as a ‘protector’ force for Taylor,” wrote Jamie Menutis, an officer for the U.S. Resettlement Office of the Department of State who took testimony from refugees of human rights abuses in asylum cases. “During their free moments, they put down their AK-47s and played with small matchbox cars in the dirt. This is an image I will never forget.”

In a perverted context, child soldiers fit Taylor’s needs perfectly. They were easy to recruit, naive enough to stay within the fold, and armed with an AK they were just as lethal as an adult. Even the youngest boys, barely able to hold the rifle, could spray bullets and hit a human target. Psychologically, child soldiers held other advantages. Youth made them feel invulnerable. Coupled with natural teen bravado and an undeveloped conscience, children offered a deadly combination in a guerrilla fighter. As one Liberian militia commander put it, “Don’t overlook them. They can fight more than we big people. . . . It is hard for them to just retreat.”

For opposing forces, seeing a child holding a weapon was unnerving, and there were several instances in other African countries such as Sierra Leone, in which Western soldiers sent as peacekeepers did not have the heart to fire at children even though they were deadly combatants.

The Small Boy Units were often looked upon with favor by their adult rebel comrades. Not only did they add numbers to the ranks, but their very existence seemed to be spiritually mandated. As one adult soldier put it, “God must think that [President] Doe is oppressive, too, because he sent us all these small boys to fight.”

Other books

Reign Fall by Michelle Rowen

Chocolates for Breakfast by Pamela Moore

Throne by Phil Tucker

Esta noche dime que me quieres by Federico Moccia

Hunted Down by His Alpha by C.J. Colton

Maid for Love by Marie Force

Winter's Thaw by Stacey Lynn Rhodes

El cuento de la isla desconocida by José Saramago

Gold Digger by Frances Fyfield

Kate Sherwood - Dark Horse 1.3 - Riding Through Fire by Kate Sherwood