AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War (16 page)

Read AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War Online

Authors: Larry Kahaner

BOOK: AK-47: The Weapon that Changed the Face of War

3.78Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Despite government initiatives to disarm citizens and destroy weapons, most are still around, and with new weapons pouring into the region daily from around the world, parts of some Central and South American countries remain gun-heavy and dangerous.

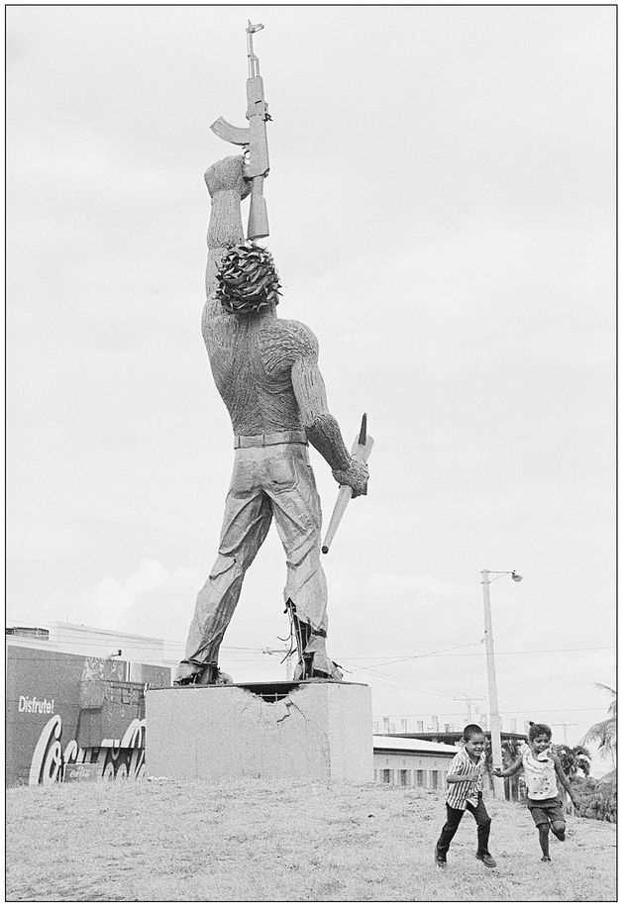

Unlike Africa, where AK-toting, poorly disciplined gangs mainly engaged in small-time subsistence looting, pillaging villages and supporting despots like Charles Taylor in his gun and blood-diamond trade, the Latin American scene evolved from violent civil wars between rebel groups and government forces to powerful, well-trained and disciplined drug cartels that operate under the guise of political ideology.

These groups are so rich and powerful that they mimic small countries, maintaining order in their strongholds, taxing drug farmers, and keeping government forces at bay. Their political ideologies, both right- and left-wing, exist mainly as the glue that supports a social, economic, and cultural infrastructure focused on growing, smuggling, and profiting from illegal drugs such as cocaine and heroin. (Afghanistan remains the largest producer of heroin, its exports reaching the United States through drug smuggling routes established and protected by South American drug cartels.)

As these groups grew stronger, they were able to purchase larger weapons—one Colombian drug cartel even had a submarine on the drawing board to smuggle cocaine—but their work-horse remains the AK, which is often paid for with drugs instead of money. This barter was so institutionalized that a de facto exchange rate of one kilo of cocaine sulfate per AK was established. (Cocaine sulfate is produced by mashing coca leaves with water and dilute sulfuric acid. This produces an easily transportable paste that is an intermediate step to producing cocaine hydrochloride—common street cocaine.)

As the civil wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala petered out in the 1990s because of exhaustion by the combatants, tens of thousands of small arms, mainly AKs, remained in the hands of former rebels and government soldiers who used them in criminal acts ranging from robbery and homicide to protection for South American drug cartels that employed Central America as a waypoint for contraband heading north to the United States. Currently, more than 70 percent of the cocaine entering the United States comes through the Central America-Mexico border, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and governments weakened by civil wars and ensuing domestic violence often are powerless to stop the traffic.

These civil wars, fueled by AKs supplied by the two superpowers, have left Central America as one of the most violent regions in the world, with crime rates more than double the world average. These crime rates not only impede democratic processes but have locked the region in widespread poverty. The Inter-American Development Bank estimates that Latin America’s per capita gross domestic product would be 25 percent higher if the crime rate were more in line with the world average.

LIKE AFGHANISTAN, NICARAGUA became its hemisphere’s premier entry point for AKs. In almost parallel fashion, the U.S. government, wanting to fight pro-Soviet regimes, covertly armed Nicaraguan Contra fighters with AKs manufactured by Warsaw Pact countries. The Soviets did the same for their comrades.

Drugs, AKs, and political dogma are so tightly bound together in this region of the world that they may never be unwound. Unless they are, however, the three will feed on each other as Latin American nations remain mired in the chaos of government corruption, violence, and severe urban poverty.

This deadly triad in Central America can be traced to U.S. intervention in Nicaragua in the 1850s when the conservative elite of the city of León invited American adventurer William Walker to fight against their rivals, the liberal elite of Granada. Remarkably, Walker was elected president in 1856, but forces from neighboring Honduras and other countries drove him out and later executed him.

From 1912 through 1933, except for one nine-month period, U.S. Marines were stationed in Nicaragua; the U.S. administrations said they were needed to protect American citizens and property. From 1927 to 1933, Sandino led a revolt against the conservative regime and their U.S. supporters, and U.S. troops finally left in 1933, but not before they had set up the National Guard, a militia designed to look after U.S. economic interests after the marines’ exit. Anastasio Somoza Garcia was put in charge of the National Guard, and he ruled the country along with Sandino and President Carlos Alberto Brenes Jarquin, a figurehead politician. Half a century later, the fragments of this National Guard would became the focal point of U.S.-supplied AKs.

With U.S. support, Somoza Garcia took full control of the country, and the National Guard assassinated Sandino in 1934. The Somoza clan held dictatorial power through torture, intimidation, and military force until 1979. During the family’s reign, which was passed along to sons and brothers, they built an enormous fortune through bribery, exports of coffee, cattle, cotton, and timber, and by accepting financial and military aid from the United States—as long as they remained anti-Communist. Like Charles Taylor in Liberia, the Somozas ran Nicaragua for their own personal benefit.

Opposition was building, however. Buoyed by the success of the Communist revolution against Cuban dictator General Fulgencio Batista in 1961, Sandinista forces backed by Cuba staged raids from Honduras and Costa Rica against Somoza’s National Guard troops. Although Cuba did not produce AKs, it received them from the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact countries as well as North Korea and supplied them to rebel forces in Nicaragua. Aside from hunting rifles and other scrounged firearms, the AK became the Sandinistas’ main weapon. Cuba had previously backed pro-Communist rebels in Angola with weapons, funding, and troops and was doing the same for the Sandinistas despite protests from the United States.

U.S. officials were torn. On one side was a dictatorship that was growing more brutal as the revolutionaries became more active. On the other side was the specter of the Soviet Union gaining a foothold in Nicaragua as it had done in Cuba. The United States continued to support Somoza with funds and weapons until December 1972, when an earthquake destroyed much of Managua, killing ten thousand people, leaving fifty thousand families homeless, and ruining about 80 percent of the city’s commercial buildings.

Instead of keeping order, Somoza’s National Guard joined much of the looting that followed the earthquake, but what happened next shocked and horrified the international community even more than the soldiers’ behavior.

With millions of dollars in relief aid pouring into Nicaragua, Somoza took advantage of the situation, keeping most of the money that was intended for victims. Funds earmarked to purchase food, clothing, and water and to rebuild Managua were diverted into Somoza’s personal bank account. By 1974, his wealth was estimated at more than $400 million. Even his supporters were sickened by the dictator’s actions, and opposition within the business community, one of his strongest allies, was rising.

The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) grew during this time as anti-Somoza sentiment grew throughout the country. Somoza responded with even more repression, prompting President Jimmy Carter to make military assistance contingent upon human rights improvements. Somoza stepped up his oppression. Street protests continued, and the country was in a state of siege. Strikes were commonplace and the economy was in ruins. Somoza relied on foreign loans, mainly from the United States, to prop up the country’s finances.

Somoza’s eventual downfall was precipitated by the assassination in January 10, 1978, of Pedro Joaquin Chamorro Cardenal, outspoken publisher of the newspaper

La Prensa

and leader of the Democratic Liberation Union (UDEL). A massive nationwide strike paralyzed the country for ten days, and Sandinista attacks on government forces continued—but Somoza clung to power.

La Prensa

and leader of the Democratic Liberation Union (UDEL). A massive nationwide strike paralyzed the country for ten days, and Sandinista attacks on government forces continued—but Somoza clung to power.

In 1978, the United States stopped military assistance to Somoza, forcing him to buy weapons on the world market. In one instance, no longer able to purchase M-16s from the United States, Somoza’s National Guard bought Israeli Uzi submachine guns and the Galil, that country’s version of the AK, first introduced in 1973. Because of his outlaw behavior, many countries refused to sell arms to Somoza. Israel was among them, at first, but the Israelis succumbed to pressure from pro-Somoza entities within the U.S. military, fearing that refusal would cut off their own U.S. funding.

The Israelis had built the Galil, named for its inventor, Israel Galili, in response to the poor performance of their standard-issue FN-FAL during the 1967 Six-Day War. (Israel Galili is often confused with Uziel “Uzi” Gal, the inventor of the Uzi submachine gun.) Having seen the reliability of the AKs used by Arab nations in battle, the Israelis realized that their rifles were not tough enough for desert conditions. In addition, the Israeli army was overwhelmingly a conscript force with most troops considered reservists available for a call-up during emergencies only. With little ongoing training, these soldiers could be hard on their weapons—leaving them in the dirt during bivouac, for example, something a professional soldier would never do—and the AKTYPE rifle could withstand abuse. (In an odd but practical concession to these unprofessional, part-time fighters, the bipod stand included with the weapon sported a bottle-cap opener. This would keep Israeli soldiers from damaging the flanges on their magazines by opening bottles with them.)

For Somoza, a major draw of the Galil was that it fired the 5.56mm round, the same as the M-16, so his army could use the tons of U.S.-supplied ammunition it still had on hand. The rifle was also inexpensive, less than $150 each.

As Somoza’s popularity waned, the National Guard became even more brutal in their attacks, including widespread bombing of León after the Sandinistas had taken control of that city. Still, Somoza would not yield to pressure for inclusion of the Sandinistas in the government.

The country continued to deteriorate. High unemployment, violence, inflation, food and water shortages, and massive debts racked the nation. In February 1979, the Sandinistas formed a junta combining several anti-Somoza groups that garnered a broad following. By March, the FSLN, now better equipped with small arms, launched a final assault on many areas, and by June these AK-wielding soldiers had secured most of the country.

In July, Somoza finally resigned, and with U.S. help fled to Miami and then to Paraguay, where he was murdered the following year, reportedly by leftist Argentine guerrillas.

Faced with a debt of $1.6 billion, an estimated 50,000 citizens dead and 120,000 homeless, the Sandinista administration was doomed from the start despite an optimistic citizenry. But even with widespread disease and lack of food and water, for many people the situation was still better than under the brutal Somoza regime.

With no cohesive government in charge, FSLN leaders formed coalitions, and finally in 1980 a government incorporating large numbers of Nicaraguans was formed. Not everyone embraced the new regime, however. President Jimmy Carter tried to work with the FSLN, but his successor Ronald Reagan, who took office in January 1981, immediately began to isolate and vilify the new government, claiming it was arming pro-Soviet guerrillas in El Salvador.

Nicaraguan problems aside, Carter had lost the election in part because Americans blamed him for not securing the release of fifty-two U.S. hostages held by Islamic fundamentalists at the American embassy in Tehran. The hostages were released twenty minutes after Reagan’s inauguration, leading to speculation that a secret deal now known as the “October Surprise” had been reached between Reagan’s campaign officials, notably William Casey, and Iranian officials to hold the hostages until after the election, thus ensuring that Carter would not win. In return, Iran would receive military and funding support to help fight their war with Iraq that had been ratcheting up for years and fully commenced on September 22, 1980, when Iraqi troops invaded Iran. This covert involvement of the United States in the Iran-Iraq war would later become a crucial element in the spreading of AKs a half a world away in Nicaragua.

As the Sandinistas took hold, the Reagan administration supported opponents with funds and military aid. The core of these were remnants of Somoza’s original National Guard, who operated hit-and-run raids from camps in Honduras where many of them had fled after the dictator’s fall from power. These Contras (from

contrarevolucianarios

) grew in strength as Nicaraguans became less enamored with the slow economic progress of the Sandinista government. Because they had to spend more and more of their budget on fighting the Contras, the Sandinistas were left with less for social reform. In addition, they grew less tolerant of legitimate opposition groups and began employing intimidation tactics against those who did not believe in the revolutionary movement. Even

La Prensa

, once ardently anti-Somoza, voiced its concern over the tactics of the Sandinistas, who, during a state of emergency declared in 1982, censored the newspaper.

contrarevolucianarios

) grew in strength as Nicaraguans became less enamored with the slow economic progress of the Sandinista government. Because they had to spend more and more of their budget on fighting the Contras, the Sandinistas were left with less for social reform. In addition, they grew less tolerant of legitimate opposition groups and began employing intimidation tactics against those who did not believe in the revolutionary movement. Even

La Prensa

, once ardently anti-Somoza, voiced its concern over the tactics of the Sandinistas, who, during a state of emergency declared in 1982, censored the newspaper.

Other books

TS01 Time Station London by David Evans

Oracle by Jackie French

SFS1 - Science Fiction Short Stories by Mani, Krishna kumar

Godless by Pete Hautman

Heres to You Mr Robinson by Barry Lowe

Saving Henry by Laurie Strongin

Super Sexual Orgasm: Discover the Ultimate Pleasure Spot: The Cul-De-Sac by Barbara Keesling

Sea of Slaughter by Farley Mowat

Adulthood Rites by Octavia E. Butler

Redeemed: Bad Blooded Rebel Series #4 by George, Mellie