After Tamerlane (9 page)

Authors: John Darwin

In these favourable conditions, the Portuguese traversed the empty seas and then pushed north from the Cape until they ran across the southern terminus of the Indo-African trade route near the mouth of the Zambezi. From there they could rely upon local knowledge, and a local pilot who could direct them to India. Once north of the Zambezi, Vasco da Gama re-entered the known world, as if emerging from a long detour through pathless wastes. When he arrived in Calicut on India's Malabar coast, he re-established contact with

Europe via the familiar Middle Eastern route used by travellers and merchants. It was a feat of seamanship, but in other respects his visit was not entirely auspicious. When he was taken to a temple by the local Brahmins, Vasco assumed that they were long-lost Christians. He fell on his knees in front of the statue of the Virgin Mary. It turned out to be the Hindu goddess Parvati. Meanwhile the Muslim merchants in the port were distinctly unfriendly, and, after a scuffle, Vasco decided to beat an early retreat and sail off home.

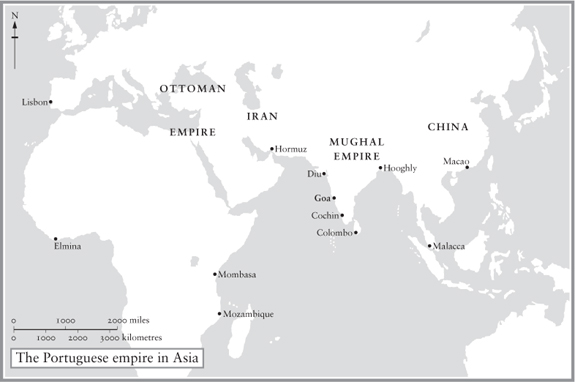

But what were the Portuguese to do now that they had found their way to India by an Atlantic route that they were anxious to keep secret? Even allowing for the lower costs of seaborne transport, it was unlikely that a few Portuguese ships in the Indian Ocean would divert much of its trade towards the long empty sea lanes round Africa. In fact the Portuguese soon showed their hand. The Malabar coast, with its petty coastal rajas and its reliance on trade (the main route between South East Asia and the Middle East passed along its shores), was the perfect target. Within four years of Vasco's voyage to Calicut, they had returned in strength with a fleet of heavily armed caravels. Under Afonso Albuquerque, they began to establish a network of fortified bases from which to control the movement of seaborne trade in the Indian Ocean, beginning at Cochin (1503), Cannalore (1505) and Goa (1510). In 1511, after an earlier rebuff, they captured Malacca, the premier trading state in South East Asia. By the 1550s they had some fifty forts from Sofala in Mozambique to Macao in southern China, and âGolden Goa' had become the capital of their Estado da India.

The Estado was neither a territorial nor a commercial empire. In part it was an attempt to force a monopoly over the trade in pepper, the most lucrative spice exported to Europe. But the Portuguese lacked the power to do this, and much of the spice trade remained outside their control.

7

Instead, the Estado became a system for extorting protection money from the seaborne trade between South East Asia, western India, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. Asian merchants had to buy a

cartaz

or safe conduct at one of the Portuguese âfactories' â Goa, Diu or Hormuz â or run the risk of plunder by the Estado's sea captains. In the Indian Ocean, after a crushing victory over the Egyptian navy at Diu, the Estado met no serious opposition, although it

was not strong enough to block the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and rule the Red Sea. None of the states that fringed the Indian Ocean had developed the naval technology that made the Portuguese caravel a deadly weapon of maritime warfare. Perhaps none, except Malacca, regarded oceanic trade as important enough to build a great warfleet. The major states of South Asia mostly looked inland. Maritime trade was left to coastal merchant communities that lacked social prestige and political influence.

8

So the Portuguese were able to enforce their naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean with comparative ease. East of the Malayan peninsula it was a different story. In the South China Sea or near Japan, the Portuguese were much more cautious. Here they found a niche as long-distance traders, convenient middlemen for a Ming Empire that disliked overseas activity by its own subjects and refused direct commercial relations with Japan.

As a result, the Estado modulated gradually from a crusader-predator into a loose-knit network of Portuguese communities, largely made up of

casados

, or settlers, and the local peoples with whom they intermarried. These Portuguese were not conquistadors carving out great inland empires. They lacked the strength, and perhaps the motive. Between Sofala and Macao, there were only six or seven thousand Portuguese in the 1540s, perhaps twice as many fifty years later.

9

Nor were they a dynamic commercial force, galvanizing the somnolent trades of Asia. Quite the contrary. The Portuguese had fought their way into Asia's trading world using the ship-handling skills they had learned in the North Atlantic. But their profits came largely from âsqueezing' the rich seaborne trade already there, until the development of Brazil after 1550.

10

As we shall see in a moment, it was the near-simultaneous venture to the Americas that allowed the Occidentals to establish themselves firmly in Asia's trading economy. Meanwhile, for the indigenous traders and shippers of the Indian Ocean and South East Asia, the Portuguese presence was a source of anxiety. For Malacca it had been a catastrophe. But for the larger states with whom the Portuguese came into contact they were at worst a nuisance, at best a convenience.

The puzzling question is how a far-flung chain of forts and âfactories' could resist the absorptive power of the societies around them. This is all the more surprising since by the late sixteenth century the

local âcountry trade' between Asian ports had become much more profitable than the thin stream of traffic dribbling round the Cape. It was not superior power or advanced technique that kept the Portuguese âempire' together, but the more prosaic advantages of a merchant diaspora. The Portuguese were a network, held together by religion and language, and with better sources of market information in long-distance trades than their purely Asian counterparts.

11

Portuguese became the lingua franca of maritime Asia. The very marginality of the Portuguese as an alien maritime subculture helped to make them acceptable to governments mistrustful of their own commercial communities. Indeed, many Portuguese made their living as freelances. At Hugli, north of modern Calcutta, one enterprising merchant gained permission from the Mughal emperor Akbar to build a trading post to ship Chinese luxuries upstream to his court. Not far away, another band made their living as slavers and freebooters under the protection of the Arakan kingdom (now the coastal region of northern Burma), then struggling to keep the Mughals out of eastern Bengal. When the Portugese slavers carried off a high-born Muslim lady (who was then âconverted' and married to a Portuguese captain), it was the Hugli merchants who had to pay the penalty. That such âsea people', occupying a niche in the maritime fringes of the Asian world, might be the harbingers of later Occidental domination would surely have struck most Asian rulers as risibly improbable.

At first sight a startling coincidence, the almost simultaneous entry of Europeans into both maritime Asia and the Americas after 1490 can be readily explained. The south-west corner of the Iberian peninsula was really a single oceanic frontier where Genoese banking, commercial and navigational expertise collaborated with local seamen, Portuguese and Spanish. Columbus, himself a Genoese, had learned his trade in Lisbon, and, like the Portuguese navigators and their backers, understood international politics and geographical exploration as a crusade to liberate the middle of the world from infidel rule.

12

His failure to win Portuguese, English or French backing for his transatlantic voyage may have reflected justifiable scepticism about his geographical assumptions (Columbus thought China lay some

2,500

miles west of Europe) or the belief that the African route was a safer

bet. His eventual success in winning the support of Castile for his enterprise (Aragon, the âother half' of the new Spanish kingdom, showed little interest) may have owed something to Castilian envy of Portugal's Atlantic ambitions and the wealth they might bring, as well as to the appeal that Columbus's crusading rhetoric exerted on the Spanish court with its

Reconquista

ethos. The capture of Muslim Granada in 1492 (the last corner of Spain to be ruled by the âMoors') brought a high tide of fervour that helped carry Columbus to the West.

Like the Portuguese explorers, Columbus profited from the knowledge of winds and currents built up during the colonization of the Atlantic islands. In late 1492 he sailed from the westernmost outpost of the European world, San Sebastián de la Gomera in the Canaries, making landfall at the Bahamas on 12 October. Having reconnoitred Cuba and Hispaniola, he found his way back to Europe via the Azores. With astonishing seamanship, he established the sea lanes used for the voyage between Spain and the Caribbean for the next three centuries, and his sailing times were hardly improved upon for more than 150 years. As an expedition to find the sea route to China, however, Columbus's voyage had been a resounding failure. His second voyage, by contrast, was a colonizing venture bringing some

1,500

Europeans to settle Hispaniola, as the Azores and the Canaries had previously been settled.

13

On further voyages in 1498â9 and 1502â4 Columbus explored the coast of the Tierra Firme (Colombia and Venezuela) and Central America.

Thus far, the Spanish venture into the Americas could be seen as a bold addition to the Iberian settlement of the Atlantic islands: a marginal expansion of the European world. But, within thirty years of Columbus's first American landfall, the conquest of the Aztec Empire by Cortés and his company of adventurers signalled that European intrusion into the Americas held a different significance from the piecemeal colonization of Europe's oceanic periphery or Portugal's hijacking of Asian trade. It is easy to assume that the conquest of the Central American mainland was the logical continuation of the Columbian âmission', and that the fall of the Aztec emperor Montezuma was the inevitable consequence of European technological superiority. A closer look at the motives and the means which transformed a tentative maritime reconnaissance into the overlordship of

a vast interior plateau suggests instead that only a unique conjuncture of geographical, cultural and demographic circumstances permitted this first great conquest by a Eurasian power in the âOuter World' of the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa and the South Pacific.

In large part, the key to Spain's transformation into a great colonial power lay in the Caribbean. The disposition of Atlantic winds and currents made it likely that the Caribbean islands â the geographic projection of the Americas towards Europe â would be the first landfall for Spanish or Portuguese sailors. Unlike the great offshore land masses of Greenland and Newfoundland, these islands were hospitable, colonizable and readily accessible to seaborne invaders. They could be conquered piecemeal and quickly reinforced from Europe. Their indigenous populations lacked adequate military organization and were tragically vulnerable to Old World diseases. Crucially, the islands lay out of contact with, and beyond the control of, the powerful mainland empires of the Maya and the Aztecs, which had no advance warning of the alien invasion. Instead, they provided a vital springboard where the Spanish could acclimatize and from where they could reconnoitre the coast of Central America. Against the Arawak peoples of Hispaniola and the other islands, they could experiment with the techniques of warfare, control and exploitation later to be used on a grander scale. The occupation of several Caribbean islands â Cuba had become the main focus of Spanish activity by 1510 â also encouraged a decentralized pattern of sub-imperial

entradas

â armed forays to the mainland â rather than a single and perhaps disastrous continental expedition. They permitted the luxury of trial and error. Above all, the Caribbean brought gold.

The alluvial gold first found on Hispaniola was vital. The resulting gold rush brought some

1,500

Spaniards to Hispaniola by 1502, and whetted their appetite for further ventures on the islands and the mainland. It was gold seized from Amerindians, or extracted with slave labour, which helped to fund the

entradas

organized locally after 1508, rather than gold from Spain. The forward move on to the American continent was the work not of princes or capitalists at home in Europe, but of gold-hungry frontiersmen spurred on by the rapid exhaustion of the islands' deposits. Without the short-lived gold rush on the Caribbean islands and the nearby Tierra Firme, the impetus

towards the territorial conquest of the mainland might have been delayed indefinitely, or certainly past the point at which the conquistadors could exploit the element of surprise and stupefaction which played such an important part in the victory over the Aztecs. Thus the Caribbean bridgehead supplied much of the motive and some of the means for this conquest.

Between 1519 and his final triumph in 1521 the first great conquistador, Hernando Cortés, was to capture an elaborate imperial regime of over 11 million people, rich in precious metals and based materially on the cultivation of maize. The colonial jackpot which Cortés's gamble brought him presents a stunning contrast with the well-merited caution which kept Europeans on the maritime fringes of Africa and Asia and warned against ill-fated schemes of conquest. Part of the explanation for Cortés's success may derive from the comparative novelty of the Aztecs' hegemony on the Mexican plateau and the hostility towards them of their subject peoples, who provided Cortés with allies and help; part from the technological superiority of the Spanish way of warfare.

14

But it would not be difficult to find other regions in Afro-Asia where similar conditions seemed to favour foreign conquest.