After Tamerlane (11 page)

Authors: John Darwin

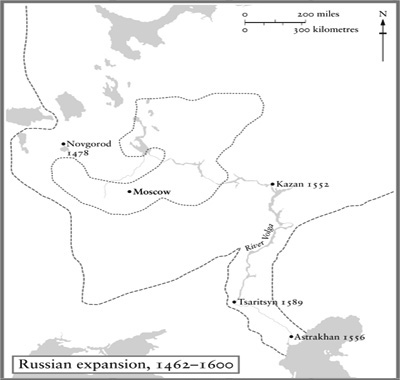

Portuguese navigators and Spanish conquistadors were the most colourful agents of the Occidental breakout in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. No less significant for the future balance of power in Eurasia was the transformation by which in little more than a century the princely state of Muscovy â until 1480 a tributary state of the Mongol âGolden Horde' â advanced over the steppe to the Caspian Sea and built a vast fur-trading empire through the Siberian forests to reach the Pacific in 1639. In a sequence of furious expansion, the Russians captured the greater part of North Asia before Chinese or Japanese influence could become predominant. They closed the northern gateway by which the steppe peoples of Central Asia had so often swept towards Eastern Europe, and seized the lower Volga before either the Ottomans or the new Safavid rulers of Iran could absorb the fragmented realm of the Golden Horde into their new imperial systems.

Even more than the Portuguese or Spanish, the Russians had been a frontier people largely cut off from the leading states of medieval Europe. âRussia and Spain', remarked a Spanish writer, â[are] the two extremities of the great diagonal of Europe.'

31

The origins of Rus' lay in the eastern migrations of Slav peoples to the edge of the forest zone, where it met the steppe and its warrior nomads (the âTatars' as the

Russians called them). The first Russian state had been centred on Kiev, where a Viking or âVarangian' ruling class had built an entrepô t to exploit the waterborne trading route that ran from Byzantium and the Near East to Baltic Europe. With the arrival of Orthodox Christianity in the ninth century, Kievan Rus' became a great cultural wedge of the Byzantine Occident, between steppe peoples to the east (Polovtsy, Khazars and Pechenegs) and pagan Lithuanians (or West Russians) to the west. Kiev became the headquarters of a vast missionary enterprise, which founded monasteries in the northern forests as far away as the White Sea. In the thirteenth century it was weakened by the rivalry of other Russian states, like Novgorod and Smolensk, and overwhelmed in the catastrophe of Mongol invasion. In 1240 the city was razed. The Russian states of the forest zone became tributaries of the Khanate of the Golden Horde, one of the four great successor states when Genghis Khan's world empire broke up in 1259. Russian rulers â and especially the exposed and vulnerable rulers of Muscovy, too close for comfort to the open steppe â found themselves acting as the agents and clients of the khanate's rulers in faraway Sarai on the Caspian Sea. Crucially, however, they retained a distinct occidental identity through the cultural influence of the Orthodox Church, which maintained its tenuous links with the Byzantine patriarchate.

32

Indeed the Mongols, who converted late to Islam, readily tolerated the Church and its doctrines.

The rise of Muscovy to a pre-eminent position among the several Russian states was due in large measure to the opportunism of its princes, who made themselves the allies and collaborators of the steppe khanate.

33

Mongol support secured them the title of grand prince after 1331; Mongol power drove back the rival Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the powerful West Russian state, Catholicized in the 1370s and linked in a union with Catholic Poland. Moscow earned the support of the Orthodox Church â a vital religious and cultural ally â through its influence with the Mongols and its leadership against Catholic Lithuania.

34

In the 1380s Muscovy exploited divisions in the khanate to assert a short-lived independence after the Battle of Kulikovo Pole. But the decisive influence on its fortunes was the vast geopolitical shock of Tamerlane's conquests from his original base in Central Asia â still the pivot of world history in the late fourteenth

century. Though Tamerlane ultimately failed to build a new empire as far-flung as Genghis Khan's, he smashed the remnants of the Mongol system, including the Khanate of the Golden Horde, which gradually broke up into the separate khanates of Crimea, Astrakhan, Kazan and Sibir'. By the 1440s Vasily of Moscow enjoyed effective independence. In 1480 his successor, Ivan III (1462â1505), beat off the last attempt from the steppe to reimpose tributary status.

The hundred years after 1480 were the vital period of Muscovite expansion, and shaped the whole course of the Occidental invasion of central and northern Eurasia. With its territorial core on the upper Volga, Muscovy became the hinge between the vast forest empire to the north and east (eventually reaching the Pacific coast of Asia) and the hard-won steppe empire of the Caspian and southern Urals.

35

But the rulers of Moscow could scarcely have sustained these imperial ambitions had they governed no more than a petty East Russian principality, held in check by Catholic PolandâLithuania and challenged as well by wealthy North Russian rivals like Novgorod, with its fur empire and Hanseatic trade. The rise of Russian power in Northern Eurasia required the consolidation of Muscovite rule over the Orthodox Russian states, and a forward movement to prevent their absorption by the dynamic joint monarchy of Poland â Lithuania that stretched from the Black Sea to the Baltic by 1504. Like it or not, the grand dukes of Muscovy could survive only by entering the European diplomatic system (to seek allies against Poland) and (no less important) by competing on cultural and ideological terms with the new-style monarchies of fifteenth-century Europe. Much of later Russian history would turn on the delicate balance between the distinctive Byzantine legacy, embodied in the Russian Orthodox Church, and the cultural borrowing from Central and Western Europe dictated by political and economic necessity.

The logic of political and cultural competition with Poland â Lithuania, where a rapid process of cultural âmodernization' was under way by the later fifteenth century (the first book was printed in Cracow in 1423),

36

was to transform Russian lands conquered by Ivan III into a dynastic state. The oligarchic traditions of âGreat Novgorod' were rooted out. Ivan projected himself as a grand monarch on the European model, blending Byzantine and Western styles of

dynastic rule. In 1492 he restyled himself âGrand Duke of Muscovy and all the Russias'. His marriage to Sophia Palaeologus, a Byzantine princess, was negotiated under papal auspices. His envoys fanned out across Europe. Italian artisans, builders and architects were brought to Moscow. The administration was reorganized around a system of âchanceries', with elaborate record-keeping and bureaucratic hierarchies.

37

The accession of Ivan IV (the âTerrible') was marked by a full-scale coronation carefully adapted from the defunct ritual of the Byzantine emperors. Perhaps to compete with the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Ivan IV promoted a monastic revival.

38

Hostility to the âLatinstvo' â the âLatin World', identified chiefly with Poland â was balanced by the opening of Russia to Germans, English and Dutch, who came as soldiers, settlers, engineers and merchants. A long series of wars was fought in the sixteenth century to keep Polish influence at bay in the West Russian lands, and prevent it from seducing Muscovy's restless boyars, the warrior-barons whose independence the grand dukes were determined to crush.

39

The internal transformation goaded by Muscovite â Polish rivalry helps to explain the success with which the Russians held on to their startling territorial gains in forest and steppe. The foundations of a fur-trade empire in the northern forests had been laid by the republic of Novgorod long before its annexation by Muscovy in 1478. Moscow sent its first expedition beyond the Urals in 1483. By the 1550s a vigorous mercantile family, the Stroganovs, were building a business empire in Siberia to bring out the fur supplied by indigenous forest peoples. This brought them into conflict with the Khanate of Sibir', which also depended upon the fur trade and control of its supply. In 1582 Ermak, a Cossack adventurer hired by the Stroganovs, succeeded in capturing the Sibir' capital. The Stroganovs' private imperialism collapsed with his death in 1585. Instead, it was the Muscovite state, directed by Boris Godunov, which carried through the military conquest of western Siberia by the end of the century.

40

The way was then clear for the hectic rush of the

promyshlenniki

(private fur traders) across the continent, reaching the Yenisei river in 1609, the Lena in 1632, the Pacific in 1639, and the river Amur in the Manchurian borderlands of China in 1643. By 1645 there were some

70,000

Russians across the Urals.

41

The legacy of Boris Godunov's decisive

intervention was to be found in the administrative control which the reorganized Muscovite state fastened on its far-flung forest colony.

The comparative ease with which the Russian conquest of the North Asian forest was carried through was partly the result of the low level of political organization and technological capacity among the stateless woodland peoples the Russians encountered. Russian firearms conferred an important technological advantage. But, as the Stroganovs

had found, it was only after the power of the Khanate of Sibir' had been broken that the Russians were free to trade and conquer. This was the crucial link between forest and steppe. By the 1590s the Russians had consolidated their hold on the neighbouring khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan, annexed to Muscovy in 1552 and 1556. Without the Ottoman backing and the trading network that propped up the Khanate of Crimea (which escaped annexation), the last survivor of the Golden Horde in Siberia was ill-equipped to resist the Russian advance.

At first sight, the Russian conquest of the steppe khanates suggests a parallel with the exploits of Cortés and Pizarro: almost at a stroke a vast swathe of hitherto unconquerable steppe â Gogol's âgolden-green ocean' of seemingly limitless promise

42

â fell under Moscow's control. Yet the Russians enjoyed few of the advantages of the Spanish conquistadors. They were well known to their foes, and could not be mistaken for gods. They could hardly hope to enjoy decisive tactical or strategic superiority on the open steppe â although Ivan IV took 150 cannon and his new musketeer infantry, the

strel'tsy

, with him to Kazan. A whole century later, the Russian attack on the Khanate of Crimea fell back in confusion, defeated by the logistics of steppe warfare.

43

A more convincing explanation of Russian success can be found in the social and political crisis of the Volga steppe societies in the sixteenth century. The khanates were not dynastic monarchies, and never made the transition to a monarchical state already under way in Muscovy. They resembled loose-knit tribal confederacies in which the khans relied on the support of tribal chieftains. Their economies depended upon trade (especially with Central Asia), the taxing of their sedentary populations, and raiding by the dominant nomadic elements into the settled Russian lands to the north and west. By the sixteenth century, however, this political economy was in disarray. Tamerlane had destroyed the great trading cities of Azov, Astrakhan and Urgench on which the steppe depended.

44

The resulting impoverishment may have accelerated the process of sedentarization by which the old egalitarian order of the Tatar nomad tribe mutated into the divided world of landowner and landless peasant.

45

With diminished military power (as a result) and less internal solidarity, the political conflicts within

the khanates became more intractable. Moreover, as successor states of the Golden Horde, Kazan, Astrakhan, Crimea and Sibir' were also engaged in mutual competition for control of the steppe. Muscovy (the fifth âsuccessor state') took advantage of this to play an active role in steppe diplomacy, and maintained peaceful relations on its vulnerable steppe frontier while it conquered the north in the 1470s.

46

By the early sixteenth century, as a result, Muscovy had grown considerably stronger than Kazan or Astrakhan: indeed, it imposed a form of protectorate on Kazan at various times before 1552, as well as nibbling away at its territory with new fortified settlements. By 1552 the Kazan khan Shah Ali was a Russian puppet. Many Tatar âprinces' had already defected to the Russians (and some had converted to Christianity), and some key tribal elements like the Nogai were intriguing with Muscovy to promote a new khan. Whether Ivan the Terrible meant to annex Kazan in 1552 is uncertain. But the city's resistance and its violent conquest ensured that result. It was with Nogai aid that the neighbouring Khanate of Astrakhan was subdued and annexed in a second lightning campaign.

Despite the drama of this steppe imperialism, it would be unwise to exaggerate its immediate significance. There was no treasure trove of minerals to finance the building of a great imperial superstructure, although Moscow merchants (and the Muscovy state) may have profited from easier access to trade with Iran and Central Asia.

47

The Volga lands were opened up to Russian peasant colonization. But beyond the river corridor Russian control was unsure, and the Volga remained a violent frontier region. Tatars continued to raid from Crimea. Even Moscow was raided as late as 1592, and its suburbs were burned. A huge effort was needed to build the fortified lines or

cherta

that were meant to deter the intruders or raise the alarm. One of these, the Belgorod Line, ran for over five hundred miles. In the early seventeenth century the Russians had to come to terms with the Kalmyks, who arrived in force in the North Caspian Steppe.

48

Further south in the Caucasus, Russian influence was checked by the new Safavid state.

49

The conquest of the Khanate of Crimea and the final closure of the Volga steppe frontier (the so-called âUral Gates' between the Urals and the Caspian Sea) had to wait until the late eighteenth century.