After Tamerlane (12 page)

Authors: John Darwin

Nevertheless, Muscovy's struggle to transform itself into a dynastic regime able to absorb the North Russian states, resist Poland â Lithuania and overawe the Volga khanates marked a decisive phase in the eventual emergence of Russia as the engine of Europe's expansion into Northern Eurasia. Though far from safe by 1600 from Polish â Lithuanian efforts to drive it north and east towards the Urals, Moscow had made the key moves to connect itself to the European state system (Polish attacks in the early seventeenth century were beaten off with Swedish help) and to equip itself with the institutions needed to sustain three centuries of imperial expansion. Building on the legacy of Mongol favour and the support of the Orthodox Church, rulers in Moscow achieved a double revolution. They converted the old military system of boyar retinues into a gunpowder army of musketeers and artillery. They centralized control over landholding through the

pomestia

, by which noble estates were held on promise of military or administrative service. The boyars had been free to carry their allegiance wherever they chose. Now they were tied into a rigid structure of fealty and obligation, while new men â called âstate servitors' â were rewarded with conquered and confiscated land. The second revolution followed in consequence. In a poor agricultural economy, the burden of taxation and service to sustain Muscovy's military effort could be borne only if the landed class enjoyed close control over peasant communities hitherto mobile, free and often rebellious.

50

The counterpart to the fixing of boyar loyalty was the bonding of peasant labour through the institution of serfdom, enforced by a ruthless combination of state authority, noble power and Church influence. As the eastern vanguard of European expansion (rather than a weak buffer state between Poland and the steppe), Russia became a Eurasian Sparta, deploying an army of over

100,000

men by the end of the century.

51

But threatened to the west by wealthier European states, and harried to the south by its still open steppe frontier, Muscovy's transformation into âRussia' or âRossiya' (âGreater Russia') was painful and traumatic. Its course was marked by internal terrorism (Ivan the Terrible's

Oprichnina

) and the âTime of Troubles' (the anarchy preceding the Romanov accession to the tsardom in 1613). Moscow was overrun by Polish armies in 1605 and again in 1610.

52

In the Americas, the human cost of Europe's maritime

imperialism was largely borne by the indigenous Amerindians and imported slaves. Overland expansion in the Old World faced tougher resistance and a harsher environment. So here the price of the Occidental breakout was a domestic regime of deepening social and political oppression, whose effects were eventually felt from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific.

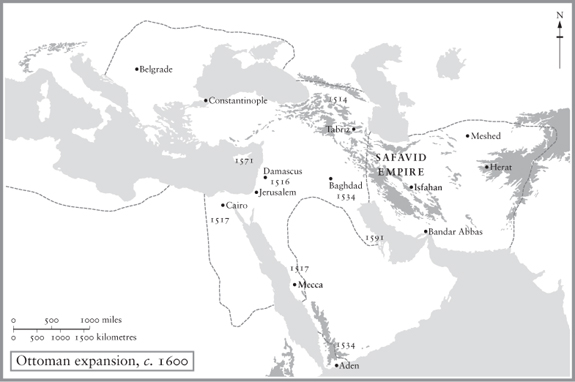

It is easy to overlook, in the drama of Europe's maritime expansion, the profound transformation that was occurring simultaneously in the Islamic lands. Two powerful trends converged in the sixteenth century to sharpen the Islamic challenge to the security of Europe, and to match the Occidental advance into the âOuter World' beyond Eurasia. The first was the consolidation of stronger and more cohesive Islamic states. The great nomadic invasions from Inner Asia subsided as gunpowder revolutionized the art of war. The second was the expansive drive that carried Islam deep into South East Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, South India and South East Asia. If the Occident emerged richer and stronger from its age of discovery, so too did the Islamic world from its age of expansion.

The western vanguard of this Islamic expansion was formed by the Ottoman Empire. With the capture of Constantinople in 1453, Ottoman supremacy in the southern Balkans was crowned by possession of the region's great imperial capital, with its command over the maritime commerce of the Aegean and Black seas. Constantinople (to the Turks, Istanbul) remained the capital of the Ottoman Empire until its final dissolution in 1922 â 4. In the decades after 1453, Mehmet the Conqueror asserted direct Ottoman rule over the far south of Greece (the Morea, 1458), Serbia (1459), Bosnia (1463), Albania (1479) and Herzegovina (1483). Mehmet's successors secured the formal subjection of Moldavia and Wallachia (comprising much of modern Romania) to vassal status (1504), captured Belgrade in 1520 and, under Suleiman the Magnificent, added Hungary to their northern tier of protectorates. Only with the abortive assault on Vienna in 1529 did the Ottomans reach what can seen with hindsight

as the limit of their apparently inexorable advance into Central Europe. To the Habsburg diplomat Ghiselin de Busbecq, who had seen Ottoman military organization at first hand, the outlook even in the 1560s was intensely gloomy. It was only Ottoman distraction with Iran, he thought, which delayed a final Turkish onslaught. âCan we doubt what the result will be?'

53

In the eighty years after 1450, the Ottomans had more than doubled their empire in Europe. No less astonishing were their territorial conquests in Africa and Asia. Having strengthened their grip in southern Anatolia, in 1516 â 17 they waged a lightning campaign that shattered the Mamluk empire that ruled over Egypt, the holy places at Medina and Mecca, and most of the Fertile Crescent from its capital in Cairo.

54

Having driven the Safavid rulers of Iran out of eastern Anatolia, the Ottomans were firmly established in Baghdad by 1534, and on the Persian Gulf by the end of the 1540s. With a naval base at Suez, they occupied and dominated the Yemen. By the 1570s almost the entire North African coastline from Libya to Morocco was under their control or suzerainty. While Spain at the western end of the Mediterranean was establishing its dominion in the Americas, the Ottomans had carved out, against much tougher opponents and on a far grander scale, a vast tri-continental empire, assembling in Busbecq's awed phrase âthe might of the whole East'.

55

To a considerable extent these triumphs can be explained by the Ottomans' ability to maintain a large standing army,

56

their use of closely disciplined infantry (the janissaries), the skilful deployment of naval power,

57

and a ruthless diplomacy. The Ottomans were fortunate in the divisions between their opponents both in Europe, where they played successfully on dynastic rivalry and Catholic â Orthodox antagonism, and in Afro-Asia. Their two Islamic opponents, the Egyptian Mamluks and Safavid Iran, failed to combine, and the Mamluks' anxiety about Portuguese sea power may have added critically to their strategic indecision. But Ottoman imperialism was based on more than military and diplomatic opportunism. To the west, towards Europe, the Ottoman sultans could exploit the â

ghazi

' tradition (of religious war to conquer and convert the heathen) to encourage their followers. It seems more than likely that their general aim was to restore the limits of the Byzantine Empire (both their

model and their foe) at the height of its power. Indeed, their Byzantine âinheritance' imposed its own demands. Like other great imperialists before and since, the Ottomans found themselves driven by the âlogic' of empire. A forward policy was needed to intimidate their numerous client states and collaborators; to avert hostile combinations; to impose direct rule where indirect control had broken down; to protect key agrarian and commercial zones by a firmer grip on strategic routes and fortresses. Nor were Ottoman rulers indifferent to commercial objectives. Their naval expansion into the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, and their effort to assert sea power in the Indian Ocean, may have been intended to profit from the networks of trade just as much as the maritime enterprise of Portugal, Spain and later Holland.

58

These methods and motives may help to explain the pattern of Ottoman conquest. But they cannot account for the successful implantation of Ottoman rule, or its remarkable durability. The inner secret of Ottoman power was its careful reconciliation between Islamic religious, legal and cultural institutions on the one hand and dynastic absolutism on the other, fashioned by the cosmopolitan statecraft of the ruling elite. Shared faith, and common acknowledgement of the Sharia or Islamic law, helped make Ottoman rule acceptable in the Fertile Crescent, Egypt and North Africa, while the sultan's role as Islam's champion against the Christian infidel gave him a strong claim on the loyalty of the faithful. In Ottoman Europe, Turkish Muslims and local converts formed the core of the political and administrative elite on which Ottoman authority ultimately depended. A shared Islamic high culture, promoting uniform values, played a vital role in binding the local and regional elites of a far-flung empire to the imperial centre. The genius of the Ottomans lay in reinforcing this Islamic solidarity with several shrewd innovations. The

timar

system in Europe and Asia Minor vested control over the revenues of rural estates in a local elite that was bound in return to provide military or administrative service to the Ottoman state. The

millet

system reconciled religious minorities, Christian and Jewish, by conceding a form of communal autonomy administered through clerical or religious leaders, appointed, like the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Constantinople, by the sultan. The most influential element in the conquered populations was thus firmly attached to the imperial

system. The Ottomans made ruthless enforcement of the law and regular taxation (as opposed to arbitrary exactions) the hallmark of their rule, at least in the initial phase of their Pax Ottomanica.

59

To many of its Christian subjects in Europe, Ottoman rule offered the same imperial virtues of order and predictability on which the British were later to rest their claim to the loyalty of the Indian peasant. The imperial capital was a cosmopolitan city, where foreigners could expect to be treated reasonably.

60

The real innovation of the Ottoman system was the

devshirme

. Until well into the seventeenth century, the Ottoman sultans balanced their dependence on the political and military service of the Turkish aristocracy by recruiting a slave army of Muslim converts (perhaps seven or eight thousand a year) separated in childhood from their Christian parents.

Devshirme

recruitment obliterated the ties of kinship and locality so feared by pre-modern rulers. It supplied the soldiers for the janissary force (a standing army of

25,000

men) stationed throughout the empire, as well as the clerks and officials from whom the sultans' most senior advisers were drawn.

61

It created the core of an educated, superior âOsmanli' ruling class, the

askeri

, whose outlook was imperial rather than local, ethnic or religious, and whose loyalties were primarily dynastic rather than territorial. To Busbecq's eye, the meritocratic selection of the Ottoman elite made it greatly superior to its European counterparts. The Ottoman system seemed a masterly synthesis of religion and politics in an empire whose dynamism astonished and horrified European contemporaries. âOn their side', groaned Busbecq in 1560, â⦠endurance of toil, unity, order, discipline, frugality and watchfulness. On our side is public poverty, private luxury, impaired strength, broken spirit.'

62

Yet the 1560s have often been seen as the climax of Ottoman strength, and the reign of Suleiman (1520 â 66) as the prelude to rapid decline as the Ottoman Empire sank towards âbackwardness'. Many standard accounts offer a kind of morality play. Ottoman âdecadence' is contrasted with the aggression and enterprise of early modern Europe, and ascribed to weak leadership, the growth of corruption, the institutional defects of the Ottoman monarchy, internal revolt, the erosion of central authority, lack of commercial and technical innovation, and a failure to adopt wealth-creating state policies.

63

A

proper discussion of this must wait for a later chapter, but the diagnosis of decline is at best premature. It was certainly true that by the mid sixteenth century the Ottoman system had begun to change. The Ottomans had ceased to expand into Europe. Their feudal cavalry (

sipahi

) were replaced by a âgunpowder' army. Ottoman military power was increasingly based not on the

timar

system but on the revenues of tax-farmers, whose provincial grip seems to have increased at the expense of the centre. The decline of the

devshirme

in the seventeenth century, perhaps under pressure from the ethnic Turkish elite, and the entrenchment of the janissaries as a hereditary caste â just what they were not supposed to be â may also have weakened the absolutism forged in the fifteenth century. The religious and social revolts in Anatolia at the end of the sixteenth century were perhaps symptomatic of an Ottoman âtime of troubles', not unlike that which accompanied the frantic expansion of Russia at much the same time. But the effect of these changes should not be exaggerated. It may be wiser to see them as signs of adaptation to a new territorial stability, more elaborate (and costly) forms of local governance, and a pattern of economic growth that benefited the class of provincial notables.

64

The so-called âdecline' of central authority may be a trick of the light.

65

Like most pre-modern states, the Ottoman Empire lacked the means to impose close administration on its subjects, and experienced alternating phases of centralization and devolution. Its real achievement in the sixteenth century was to create the basis for a decentralized but surprisingly cohesive Ottoman âcommonwealth' that stretched from the Maghrib to the Persian Gulf, and from the Habsburg frontier to the Safavid. The real legacy of Suleiman the Magnificent and his predecessors was not an absolutist state, but a network of Islamic communities ruled over by âOttomanized' elites, who enjoyed provincial autonomy while remaining loyal to, and dependent upon, the authority, prestige and legitimacy vested in the imperial capital in Constantinople. Less fearsome in European eyes than the aggressive despotism of the early sultans, the Ottoman âcommonwealth' was to prove remarkably durable. Its survival was scarcely in question before the mid eighteenth century.