After Tamerlane (64 page)

Authors: John Darwin

These amazing events marked the final collapse of the Europe-centred world order that had seemed so secure before 1914. They also revealed the terrifying fragility of the âliberal world', whose post-war renewal had been loudly proclaimed. It was not just a matter of the

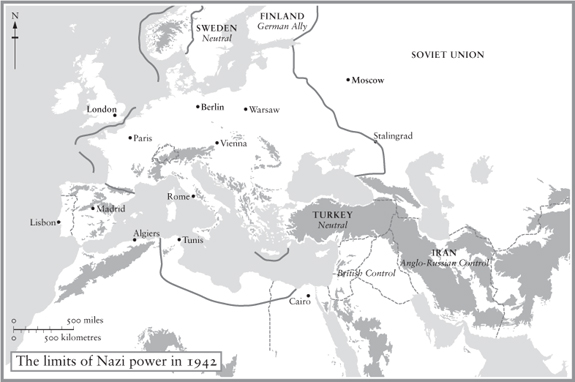

end of free trade. The 1930s had seen a scale of political violence in both Europe and East Asia that defied past comparison. Thought-control, propaganda and physical force became the daily recourse of authoritarian governments. Ideological war was waged with uncompromising ferocity. Normal feelings of humanity gave way under the strain. Most terrible of all was the boiling up not just of racial antagonism but of programmatic racism. It reached its ghastly climax in 1942, perhaps the most critical year in modern world history. A bureaucrats' conference at Wannsee, near Berlin, signalled the moment at which the Holocaust became policy in the German government.

101

That year, 1942, was âthe most astounding year of the Holocaust, one of the most astounding years of murder in the whole history of mankind'.

102

Almost half of all the Jews who fell into Nazi hands were killed in the twelve months after March 1942. In this orgy of murder we might also see the end of a world. What had opened up this moral abyss?

It is tempting to dismiss the 1930s and '40s as a freakish era of fanatics and madmen. There is no warrant for this. The process is complex, but the main lines of causation seem clear enough. At the root of the violence, the hatred, the murders, the search for cultural seclusion and economic self-sufficiency lay the clash between the two great forces that had shaped the world after 1890. The first was the intense globalization that opened up cultures, economies and political systems to external influence on a massive scale and at tremendous speed. For all the attractions of this, it was hardly surprising that in many societies there were multiple symptoms of distress and alarm, including widespread movements for cultural and racial âpurification'. The second was state-building. State-building was stimulated by many of the forces that promoted globalization: improved communications, the rise of large-scale industry, and the growth of new communities. It could also exploit them to create newkinds of authority and new techniques of control. State-builders found that they could harness the fear of the foreign to strengthen their claim to patriotic obedience. Until 1914, globalization and state-building had advanced together in a precarious balance. But the great double crisis of the early twentieth century wrecked this uneasy equilibrium. The First World War and its outcome destroyed the legitimacy of international order, the political

framework on which globalization depended. In Europe's largest states, Russia and Germany, the shock of defeat bred a violent reaction against economic and cultural openness. The great contraction of trade after 1930 gave a savage twist to the mood of revolt. The experiment in globalism had been a disaster, and its final demise could not be far off â a conviction shared by Communists, fascists and Japanese pan-Asianists. In the coming struggle for power, and perhaps survival, all that really mattered was the strength and cohesion of the nation state and the size and scale of its zone of expansion. In a fragmented world with no collective will, there were few restraints. The vast Eurasian war that filled the horizon by mid- 1942 was the crisis of the world.

Empire Denied

8. The newface of war: nuclear test in the Marshall Islands, 1952

To those tossed about in its terrible wake, the Second World War was the end of the world. It smashed the flimsy structure of international society, already fractured after 1918. It tore down states or wrecked their workings. It blocked the channels of trade, and created new forms of economic dependence. It loaded peoples and governments with huge new burdens that they could barely carry either financially or physically. It fashioned newforms of coercive power through propaganda, policing and an intricate web of economic controls. It raised ideology to a screaming pitch as part of the struggle to motivate and mobilize. It spread a vast tide of violent disorder extending far beyond the zones of battle or the march of armies. It displaced, enslaved or murdered huge numbers of people, especially in Europe, South East Asia and China. However the war ended, it was bound to cast its shadowon the peace that followed. The massive task of reconstruction would fall on peoples and governments already exhausted and disoriented.

1

In the post-war world, social and political cohesion â or discipline â would be at a premium. Those states that maintained (or exceeded) their wartime production would be at a great advantage in any struggle for power. One thing was certain: there was no going back to the status quo, even if such a thing had existed in the turbulent 1930s. As much as the world before 1914, the pre- 1939 world had gone for good.

Of course, this did not mean that the world was a moonscape in which everything would be new. For all the terrible stresses of the conflict, large areas of the globe â in the Americas and Africa â had preserved their social and political order. In much of the rest, the strongest wish of civilian populations was (almost certainly) to free themselves from the demands of authority and recover some shreds of normal domestic life. They would begrudge new rules, new calls on their labour, or new material hardships. The victor powers would bring to the peace many old aims and assumptions, however much modified by the war's extraordinary course. Wherever they could, they would harness the forces left behind by the war to build a new order in tune with their interests â if they could decide what they

were. There was little chance in reality that they would all agree on a blueprint for peace (another legacy of the inter-war years), or have the will or the means to impose it globally. Hence the post-war world (whatever the dreams of prophets and planners) was not a new beginning or a cure for conflict. It was like a bombed-out city in which the most urgent need was to shore up the buildings that had survived the blast and divide up the remainder between rival contractors. But with little agreement on where to rebuild or what to demolish, and with competing claims to some of the grandest ruins, reconstruction was slow, conflictual and bitter. After 1949, this poisonous atmosphere became even more acrid, since both superpowers now possessed the means for massive destruction using atomic weapons. This was the setting in which old empires were broken and new ones assembled.

The turning point in the global war came in 1942â3. At the Battle of Midway in June 1942, America destroyed the offensive power of the Japanese navy in the western Pacific. At Alamein in OctoberâNovember 1942, the GermanâItalian effort to capture Egypt and break the British Empire in two suffered a decisive setback. Above all, at Stalingrad and the tank battle of Kursk, German hopes of defeating the Soviet Union were effectively shattered. Whatever successes they scored, after mid- 1943 the Axis powers could not win outright and there could be no new world order designed in Tokyo and Berlin. What remained hugely uncertain was when and how the war would end, the state of the world when it did, and the balance of strength between the victorious powers when the shooting stopped. An Allied disaster in Normandy in June 1944, or a Japanese victory at Imphal on the frontier of India at much the same time, would have had drastic consequences.

Meanwhile, on the side of the âUnited Nations', as the anti-Axis coalition began to style itself, the demise of the old colonial order was the public aim of its two strongest allies, the United States and the Soviet Union. In Moscow, hostility to empire (except of the Soviet variety) was axiomatic. Its destruction would herald the inevitable fall

of capitalism. The American president Franklin D. Roosevelt made no secret of his dislike for European colonial rule, though out of deference to Churchill he reserved much of his fire for the sins of French rather than British colonialism. But it was widely assumed among American policymakers that, for all the heroism of their island defence, the British were irredeemably decadent as an imperial power. Indeed, this view was echoed within Britain itself. The fall of Singapore, the loss of Malaya and Burma, the feeble performance of the British forces, and the lack of enthusiasm for the imperial cause by Britain's Asian subjects, notably in India, all seemed to showthat Britain's century of dominance in South and South East Asia had come to an end. To cling to old-style imperialism would be futile and dangerous. In

Soviet Light on the Colonies

(a Penguin Special in 1944), one expert critic compared British colonial policy unfavourably with Soviet practice in the Central Asian republics.

2

The government itself, worried by the hostility of American public opinion, waged a charm offensive to present imperial rule as a beneficent partnership to promote democracy and development among âbackward' peoples.

3

Colonial governments were given the nod to widen political life and hold more elections. None of this was lost on colonial politicians. Whatever the outcome of the war, it seemed certain to break the pre-war stalemate in colonial politics. One grand symbol of change was already in evidence. In 1943 the remnants of China's unequal treaties were at last swept away when the British abandoned their surviving privileges there as so much useless lumber.

Yet the course of the war offered no reassurance that the world of empires would be smoothly transformed into a world of nations. The first region made secure by the Allied powers was the Middle East. The immediate effect was to restore the primacy that the British had enjoyed since 1918. Indeed, victory allowed them to entrench it more deeply â or so it appeared. They had made Cairo the centre of a huge operational sphere in the Mediterranean as much as in the Middle East. The âSuez Canal Zone', demarcated in the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936, was a great military enclave, housing thousands of troops, as well as workshops and stores, training areas and airfields. It was a bastion of power from which British military might could be dispatched in any direction. In fact the British showed little sign of

believing that their Middle East imperium should be given away. They feared a revival of Soviet power, and suspected Stalin's designs on northern Iran (occupied during the war by Soviet troops) and the Turkish Straits. They were determined to protect their oil concessions in south-western Iran, and their refinery enclave at Abadan on the Gulf. They sawthe Middle East as the vital platform from which to project their authority in the eastern half of the world. Their aim was not to impose old-style colonial rule, abandoned as impractical two decades before, but to reshape local politics in convenient ways. Their basic assumption was that âmoderate' nationalists in Egypt, Iran and the Arab countries would accept a more âdiscreet' British presence in exchange for promises of protection against external attack and a generous package of economic aid. What they failed to foresee was howquickly the ArabâJewish conflict in Palestine (governed by the British under an international mandate) would be intensified by the torrent of Jewish refugees who poured in at the end of the war, and howbadly their influence would suffer from the Arab belief that the creation of Israel (and the Arab defeat in the Palestine war that followed British withdrawal in 1948) was an act of British betrayal. The end of empire in the Middle East was to be anything but a consensual transition to a nation-state age.

The question of Palestine, the risk of Anglo-Soviet rivalry and the growing importance of its oil reserves linked the future of the Middle East to the outcome of the war in Europe. In an ideal world, there would have been a European settlement to revive the pre-war states system, restore democratic self-government, and promote economic recovery. Had such a ânewEurope' emerged to balance the power of the United States and the Soviet Union, the general pattern of the post-war world would have been very different. But the course of the war made such an outcome impossible. The Allies' insistence on âunconditional surrender' (partly from loathing of the Nazi regime, partly from fear that negotiation would split them), and Hitler's resolve to fight to the end, turned almost all of Europe into a vast battleground in 1944â5. Much of the continent had already become a colossal Nazi empire mobilized for war, obliterating pre-war states, uprooting pre-war communities, liquidating pre-war minorities. In the terrible death throes of Nazi imperialism in Eastern, Western and

Central Europe, the scale of the violence, ethnic and ideological divisions, and the stigma of collaboration, whether forced or not, were a fateful legacy. In the climate of fear, retribution and hate, the task of reviving democratic self-government (in Eastern Europe especially) was desperately vulnerable to social or racial conflict and external pressure. There could be no swift restoration of Europe's place in the world. What occurred instead was a succession struggle between the victor powers and their local allies to win control of the defunct Nazi empire.