After Tamerlane (63 page)

Authors: John Darwin

It was thus hard to envisage the early demise of the European empires. Indeed, the British, who had the largest, were tending if anything to strengthen their hold on those parts of their system that had (like Argentina) become more dependent upon the British market or (like Australia and NewZealand) felt more in need than ever of British strategic protection. Across the vast areas of Africa, Asia and the Middle East where European imperialism depended upon the grudging acquiescence of local allies and clients, what had really set in was a form of stalemate. The colonial impetus (never strong in most places) had been lost. The resources of power had run low. The sense of purpose had dissolved. But colonialism remained a âgoing concern'. Its local enemies had yet to find a way out of the labyrinth it had built. It would take a huge external shock to help blast a path.

Imperialism can be defined as the attempt to impose one state's predominance over other societies by assimilating them to its political, cultural and economic system. As we have seen already it was not just a European phenomenon, although Europeans had tended to carry it furthest. Nor was it practised in only one mode. Sometimes it relied upon the direct political control of the zone of expansion. But it was often convenient to defer or disguise the fact of foreign predominance by leaving in place a notionally sovereign government. Sometimes it led to the displacement of peoples by a mass of newsettlers colonizing the land. But in Europe's advance into Afro-Asia this trend had been weak. Quite often its motive had been to delimit a sphere of economic exclusion, reserving trade and investment to the imperial power. But not invariably: the biggest empire of all, the British, had practised free trade until the 1930s. It was usually based upon an ideological claim (the âcivilizing mission') and an appeal to notions of a cultural hierarchy in which the colonizers' capacity for âmoral and material progress' was sharply contrasted with the regression of the colonized. However, for all its arrogance, this cultural imperialism lacked the brutal certainty of âbiological racism'. Belief in the limits set by ethnic descent on intellectual or moral development was far from uncommon among late-nineteenth-century imperialists, but it was not universal. In both the French and the British empires (by contrast with the United States) the potential for equality among persons of all races remained the formal position in law, in institutions and in official ideology.

Imperialism should thus be seen as a continuum with wide variation in its objects and methods. In a nowfamous argument, the greatest historians of British imperialism showed that its mode of expansion differed from place to place and was mainly determined by the scope for cooperating with local elites. Where British interests required more than these elites would deliver, âformal' rule was imposed â but not otherwise.

92

This insight can be widened. States that cherished imperial ambitions varied considerably in their expansive capacities, in their notions of self-interest, and in the opportunities available. A shortage of capital and limited geopolitical leverage increased the

appeal of an exclusive empire but reduced the chance of winning a large one. Coming late to the race might mean that the rich pickings had gone before there was time to stake a real claim. The costs and risks of expansion at a particular moment might seem much greater to the ruling group in the would-be imperial power than any possible benefit. It was partly this that ensured that the forward surge of empires after 1880 had passed off without a resort to arms between the European states. Partition diplomacy also reflected the fact that where the stakes were highest â in the Middle East and China â the existing order had yet to collapse and no single power had the motive or means to enforce a division.

Historians have been mesmerized by the imperial rivalries of the late nineteenth century. But the ânewimperialism' out of which they grew was a tepid affair: it had little in common with the brutal expansions of the 1930s and '40s. It was then that the struggle for empire, repressed by the outcome of the First World War, reached its savage climax. In these decades, the grab for territory by would-be imperial powers assumed an urgency that was infinitely greater than before 1914. The threat it posed to international order could not be defused â as in earlier times â by diverting its impact into the weakly ruled spaces of the Outer World. Three crucial conditions reinforced its ferocity and wrecked the chances of compromise. First was the depth of the economic crisis after 1930, and the fear it aroused of a vast social breakdown. Second was the violence of the ideological warfare that raged between states â communist, fascist and liberal â and the gulf of mistrust that this served to widen. Third was the fear of impending encirclement â economic, racial or geostrategic â in a world whose division into mutually antagonistic blocs was the most likely future. To make matters worse, the regimes that felt most at risk from these dangers â Germany and Japan â were the least inclined to prop up the balance of power or the old social order, the two great brakes on imperial adventurism before 1914. Still less were they likely to treat the world's existing borders as if they were legitimate. The newimperialism of the 1930s was the toxic product of an anxious, lawless, insecure world.

What form did it take? The prime mover was Germany. Once Hitler came to power, the German revolt against the leaders of the âLeague

World' became unstoppable. By openly flouting the disarmament rules of the Versailles Treaty, militarizing the Rhineland, uniting with Austria (the Anschluss) and forcing Czechoslovakia's dismemberment with aggressive diplomacy, Hitler humiliated and demoralized the two guarantors of the post-war order, Britain and France. He encouraged the defection of their once junior partner, Italy, nowalso a rebel against the League World's rules. Hitler's imperialism â the quest for

Lebensraum

â targeted Eastern Europe, the Ukraine and Russia. It was meant to be built over the physical and ideological ruins of the Soviet empire. By contrast, he took little interest in the colonial empires of Britain and France, and regarded Germany's pre- 1914 challenge to Britain as a catastrophic error.

93

But in 1939 he discovered that the two Western powers would not let him become the imperial hegemon of Eastern Europe without a fight. To win that war, the necessary prologue to the main struggle against Stalin, Hitler concluded the NaziâSoviet pact of August 1939. Both partners bought time: time for Germany to win supremacy in Western and Central Europe; time for Stalin to prepare for the struggle that was bound to come. Of the two, it seemed for some months as if Hitler's gamble was bigger. After all, if the First World War was anything to go by, it was hardly likely that he would be able to defeat Britain and France in an all-out war, especially if he had to look over his shoulder at a hostile Russia. Even after the first phase of the war was over, and Poland was shared out between its two brutal neighbours, an unofficial armed truce â the âphoney war' or

drôlede guerre

â reigned in the west. If Germany could not win quickly, it was widely assumed that its overstrained economy would collapse long before the economies of the British and French with their investments and empires.

94

After six months of âwar', maybe the Germans had lost their nerve. âHitler', said Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister in April 1940, âhas missed the bus.'

95

But in the lightning war of MayâJune 1940, and against all reasonable prediction, Hitler made himself master of most of continental Europe. From the Atlantic coast of France he could apply the tourniquet of submarine warfare to the sea lanes of Britain. Sooner or later he could begin the conquest of the Soviet Union and secure German domination from the Atlantic to the Urals. In the meantime, his dra

matic defeat of the Western powers signalled the meltdown of the post-First World War order â and not just in Europe. Once France had fallen, Italy entered the war to seize a Mediterranean empire, attacking Greece and Egypt, the strategic bastion of British Middle Eastern power. If the British lost Cairo (the grand centre of their imperial communications) and the Suez Canal, the road would be open for an Axis advance to the Persian Gulf and (eventually) the frontiers of India. For Hitler, ironically, the Italian advance into Greece and Egypt was a damaging distraction. It delayed the grand assault on the Soviet Union, âOperation Barbarossa', that he opened in June 1941. As the German armies tore into Russia and raced across the Ukraine, a huge geopolitical revolution was under way. There was every sign that within a year the Germans would control the Soviet land mass west of the Urals, as well as the Caucasus with its supplies of oil. They would have built an empire on the grandest of scales. They would command what Mackinder had called the âheartland', and be the dominant power in continental Eurasia, driving Britain (and America) to its maritime fringes and the Outer World beyond. âWe should be the blockaded party,' declared an American expert.

96

It was inconceivable, if that happened, that much would survive of the old colonial order in Asia, Africa or the Middle East. Indeed, by mid- 1941 the signs of a crisis were already apparent in the largest colony of all. Faced with German supremacy on the European mainland and the newMiddle Eastern threat, the British had been forced (against their original plans) to mobilize Indian resources. Nowthey would have to pay the price demanded by Indian nationalists and Muslim sub-nationalists, or face a political revolt. They embarked upon the twisting path of concession that led by mid- 1942 to the fateful promise of Indian independence at the end of the war.

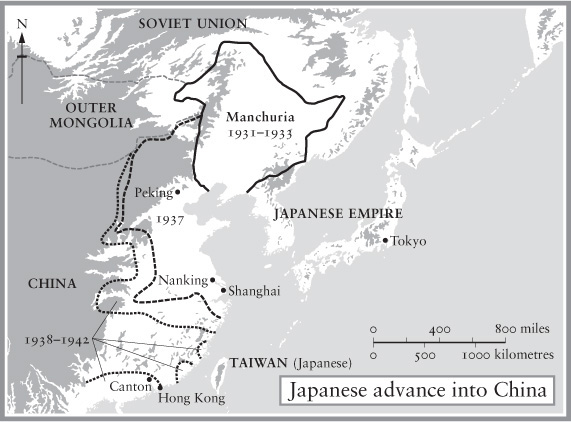

At the eastern end of Eurasia, a second vast upheaval had already begun. After their conquest of Manchuria, the Japanese had continued the slowpenetration of North China, and had dragged Inner Mongolia into their sphere of control by mid-1936. In July 1937 their army in China clashed with the forces of the Kuomintang government and began an all-out war. Tokyo's objective was to make China a part of its East Asian system, cutting off its connections with the West and Russia. Japan's imperialism was fuelled by a sense of cultural anxiety,

by the ideological appeal of a âpan-Asian' revolt against the colonialist West,

97

and by a growing belief that Europe's power in Asia was in steep decline.

98

Japan had enjoyed economic success in the 1930s, but its vital markets abroad were acutely dependent upon good relations with Britain (while the British ruled India) and the United States. Of all the great powers, Japan was most vulnerable to the external disruption of its industrial economy: a commercial empire of its own was the best guarantee against the catastrophic effects of this. Indeed, the high command of the army, the dominant force in the Tokyo government, assumed that the world would soon be divided into regional spheres and closed economic zones. In a future war, the Soviet Union and Britain could be expelled from East Asia. Meanwhile, so it reasoned, the gradual extension of Japanese power over China could be pushed ahead without the risk of war with the United States, whose acute hostility towards the Soviet Union would balance its dislike for Japan's empire-building.

99

The striking failure of the British and

Americans to agree a response to Japan's attack upon China, the 1938 United States Congress decision against building newbattleships, and the defensive posture of the United States Navy in the Pacific all seemed to confirm this confident judgement.

100

It turned out to be wrong. The British and Americans did not back down: both continued to send help to Chiang Kai-shek even after he was driven from Nanking to Chungking in the far west of China. But London and Washington also miscalculated. They discounted Japan's willingness to confront them militarily. After June 1940 and the fall of France, however, Japan's hand was much stronger. On 23 September, Hitler's client regime in France allowed the Japanese army into French Indochina. A fewdays later (on the 27 th) the Japanese signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, perhaps to deter more Anglo-American help to the Kuomintang government. The following April they made another bargain. In August 1939 the Japanese army had fought a crucial battle against Soviet forces at Nomonhan in Mongolia. The Red Army won. Both sides drew the moral that further fighting was pointless â for the time being at least. Both sides were anxious not to fight on two fronts. The Neutrality Pact of April 1941 formalized this position. It freed the Soviet army to fight in the west and the Japanese army to wage a new war in the south. In July 1941 it entered southern Indochina, the launch pad for the invasion of Thailand, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, with its great reserves of oil. When Washington riposted with an oil embargo (80per cent of Japanese oil still came from America), the decision was taken for a pre-emptive war. With the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December and the capture of Singapore just over two months later (victories as astonishing as Hitler's in the west) Japan became master of the Asian Pacific. Colonial South East Asia had fallen: the invasion of India seemed just a matter of time. By mid- 1942 the Soviet empire was reeling; the British was on the ropes. Two new imperialisms were about to divide Eurasia, and then perhaps the world. A ânew order' was coming.