After Tamerlane (54 page)

Authors: John Darwin

But it was not merely a question of what the imperialists wanted. Just as important was the tenacious resistance shown by the Chinese. It had always been difficult to break down the cohesion of Chinese authority, resting as it did on the self-interested loyalty of the scholar-gentry class to the dynastic regime that gave it employment. It might have been expected that the sequence of disasters since 1894â5 would have weakened the Ch'ing claim to the âmandate of heaven'. And so it did. But the paradoxical result was a new political atmosphere much more fervently hostile to foreign interference. The 1890s had seen the rapid growth of a political movement that rejected the idea that Chinese unity depended on dynastic rule. Sun Yat-sen and his followers insisted that China was the nation state of the Han (Chinesespeaking) people and could be governed only by their chosen leaders.

116

The Ch'ing or Manchu dynasty was an alien tyranny.

117

Nor was Sun's nationalism the only form of Chinese political militancy. The newcommercial life around the treaty-port towns created fresh social forms. Associations sprang up to serve the newurban middle class self-consciously creating a âmodern' Chinese society.

118

Treaty-port industrialization produced a Chinese working class, a popular mass that could be used to intimidate foreign interests and enclaves. The provincial gentry, who had enjoyed increasing autonomy since the Taiping Rebellion, took over the role of defending China against the foreign threat from what increasingly seemed a corrupt and impotent dynasty. When Peking resumed the path of reform after the Boxer crisis, it played into their hands. The newarmy (modelled on those of Europe and Japan), the newbureaucracy, the newschools and colleges, and the abolition (in 1905) of the age-old examination system with its Confucian syllabus broke what remained of the old bonds of loyalty between the scholar-gentry class and the imperial centre. In the provinces, the scholar-gentry officials blocked every effort to use the railway concessions to extend foreign influence. âRailways are making no progress in China,' the

Times

correspondent told his foreign editor.

119

To British financiers, like Charles Addis of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, the Chinese demand for ârights recovery' meant that, while foreigners could invest in the building of railways, they could not hope to control them.

120

When the Peking government, in a desperate effort to restore its dissolving authority and bolster its finances, proposed to take the new railways away from the provincial authorities (an imperial edict in May 1911 ânationalized' all trunk lines),

121

it triggered a revolt that brought down the dynasty. The end of Ch'ing rule in 1911 opened four decades of turmoil for the Chinese people. But it also signalled the end of the era when China's subjection to a

Eurocentric

world system might have been possible.

Japan had played a crucial role in checking the advance of European influence in East Asia after 1890. Ironically, it had been Japanese victory in the war of 1894â5 that had set off the race for bases and concessions among the European powers. But Japan did not play the part of âlittle brother' to the Western imperialists. Japanese opinion remained deeply suspicious of European intentions, and deeply fearful of a combined Euro-American assault on Japan's precarious autonomy. The Europeans, remarked Ito Hirobumi on his 188 2 tour of inquiry into Western constitutionalism, âhelp and love their kith and kin and seek gradually to exterminate those who are remote

and unrelated⦠The situation in the East is as fragile as a tower built of eggs⦠We have to do our utmost to strengthen and enlarge our armament.'

122

In

Datsua-ron

(âLeave Asia, enter Europe') (1885), the great prophet of modernization Yukichi Fukuzawa equated Asia with backwardness. But his aim was not that Japan should ally with the Western powers. Instead, Japan's manifest destiny was to assume the leadership of Asia to secure Asia's freedom. Indeed, Japanese thinking reflected a deep ambivalence towards China: contempt for Chinese âbackwardness'; desire for China's resources; fear that, without a pre-emptive move, much of China would fall under European control. There was a plenty of sympathy for Chinese nationalism, and many thousands of Chinese students spent time in Japan. In turn, Japan's striking success in reforming its government and keeping the foreign powers at bay made the Japanese model very influential in China.

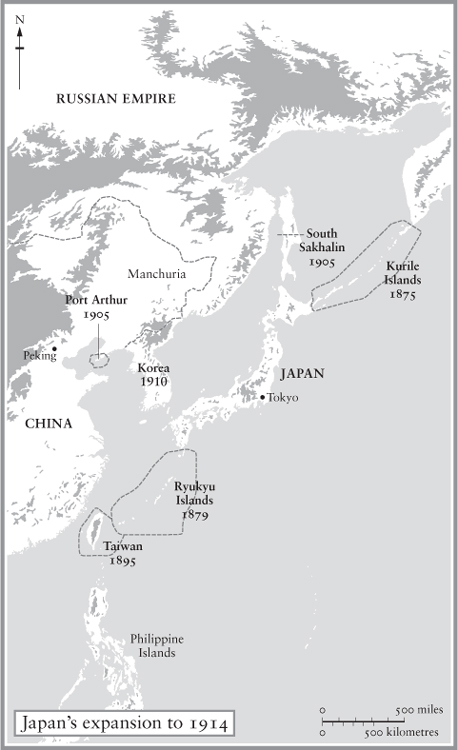

Of course, Japan had done more than set an example. Since the 1870s, it had followed a policy of wary resistance to Russian expansion in North East Asia. By the 1890s this mutual suspicion was focused on Korea â in Japanese mythology âthe dagger pointing to our heart'. Russia deeply resented the rise of Japanese power there after 1895. A stand-off agreement in 1898 exchanging Russia's preponderance in Manchuria for Japan's in Korea broke down with the massing of Russian troops at the time of the Boxer Rebellion. When the Russians refused to withdraw from Manchuria or concede Japanese claims to pre-eminence in Korea (where Tokyo's control was far from secure), a resort to war became inevitable. The result was astonishing. When Russia's Baltic fleet sailed round the world to crush the newJapanese navy, it was annihilated in the Battle of Tshushima (May 1905) in the narrowseas between Korea and Japan. Soon afterwards a numerically inferior Japanese army defeated the Russians in the Battle of Mukden in the heart of Manchuria. In the peace treaty that followed, the Japanese took over Russia's bases on the Kwantung peninsula and its commercial concessions in southern Manchuria, and received the southern half of Sakhalin, the strategic island lying north of Hokkaido. The way was cleared for a protectorate over Korea, converted to full annexation in 1910. In a single blow, Japan had become the strongest naval and military power in the region; its consent would be needed before any outside power intervened in force.

Japanese strength should not be exaggerated. The struggle with Russia had tested Tokyo's financial resources to their limit. Japanese policymakers feared a Western backlash against their imperial expansion. âManchuria is not Japanese territory,' warned the veteran statesman Ito Hirobumi.

123

American antagonism became more explicit.

124

Nevertheless, Japan's ascent was remarkable. Japan had become a colonial power in East Asia. It had acquired a modern army and navy (most of the warships were built in Britain). It had defeated a great European state in war. It had cast off (by negotiation) the unequal treaties that granted Westerners extraterritorial privileges (China had to wait until 1943 to do likewise), and regained full tariff autonomy (in 1911). It had become a de facto great power, with a sphere of interest that was safely remote from the centre of gravity of its most likely rivals. Already it loomed over the Western commercial presence in China in a way that aroused mixed feelings of envy and alarm.

125

But howhad Japan succeeded in this muted but highly effective challenge at a time when the European states were at the height of their power?

In part, perhaps, through Western observers persistently underestimating Japan's sources of strength. For obvious reasons, Japan was not well reported in the Western press, and even seasoned onlookers found Japanese politics very hard to explain. In Victorian Britain, it was Japanese quaintness that attracted most attention. Japan was an âelf-land' ruled by a mikado (the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta opened in 1885).

126

A catastrophic miscalculation of Japanese strength and skill lay behind Russia's naval disaster in 1905. But Japan also enjoyed a unique geopolitical niche from which to defend its interests. It occupied a borderland zone between continental Eurasia and the Outer World. It lay at the furthest remove from the European maritime powers and European Russia, and was barely within reach of either. (Even in the steamship era, Tokyo was thirty-two days' sailing from the British ports, and lay 1,600 miles from the British base at Hong Kong, itself a far-flung outpost of British naval power.) From the 1870s, Japanese governments had skilfully exploited this benefit to consolidate their grip on the maritime and landward approaches to the Japanese archipelago. A treaty with Russia in 1875 had made the best of a bad job by exchanging Japan's claim to Sakhalin for the Kurile Islands. A fewyears later the Ryukyu Islands that stretched

southward to Taiwan were absorbed into Japan.

127

Taiwan itself was a frontier society where Chinese control had never been thorough. It was one of the prizes the Japanese kept after their war with China in 1894â5. The penetration, occupation and eventual annexation of Korea, control of the Kwantung peninsula, and the recovery of southern Sakhalin completed the defensive ring surrounding the home islands. The risk of invasion â an age-old anxiety of Japanese governments â had been rendered almost null.

This would have counted for less had Japan's internal changes destabilized its politics, threatened foreign persons and property, and given scope for interference by the European great powers. The line-up of France, Russia and Germany to limit Japan's gains from China in 1895 showed that this threat could not be ignored. What was critical here was Japan's distinctive path of economic development. As we sawin a previous chapter, by the 1880s Japan was well on the way to competing successfully in international trade: not just in local specialities like rawsilk, but in cotton yarn and cloth â perhaps the most widely traded manufactured product. But, crucially, Japan's trajectory towards industrialization did not depend upon heavy imports of capital, the most dangerous source of external dependence. Though 4 million people worked in industry by 1913, almost all were in workshops employing five people or fewer and using little or no machinery.

128

Very cheap labour (especially that of women), not mechanized efficiency, was Japan's ticket of entry into the global economy.

129

Imported technology was adapted and simplified, reducing both its cost and Japan's dependence upon foreign expertise and parts. And behind this industrial vanguard lay a huge agrarian sector that still employed the vast bulk of the population. As late as 1903, less than 8 per cent of Japanese were classified as urban.

130

The result was a society in which foreign influence had been carefully filtered (not least by the barrier of language), and where social change had been sharply limited. In the countryside especially, the old rural hierarchy (requiring social inferiors to step aside for their betters and showexaggerated deference) was still in force. In more intellectual circles, support for political and cultural adaptation coexisted with a deep suspicion of

Oshu-shugi

â Europeanness â with its overt materialism, social divisions and cultural arrogance. Official attitudes to Chris

tianity were also hostile. Mistrust of the foreign remained deeply ingrained. In a famous incident, the future Tsar Nicholas of Russia, while visiting Japan in 1891, was attacked and wounded by a policeman caught up, so he thought, in a Russian invasion. In such a climate, it is not difficult to see why the samurai statesmen of the Meiji era were able to impose such an authoritarian version of the modern state. The 1889 constitution, intended to crown Japan's acquisition of Western-style sovereignty, entrenched the power of the SatsumaâChoshu oligarchs, the

genro

or elders who chose the cabinet. Barely 1 per cent of the population had the vote. The Diet, or parliament, could not change the government. Control of the army and navy was carefully separated from the civilian ministers. An upper âHouse of Peers' was filled with appointees from Satsuma and Choshu. And, to clothe this artful distribution of power with an aura of sanctity, it was shrewdly presented as the loyal application of âimperial right'. The emperor and âemperor-worship' became the focus of a patriotic cult to be promoted in schools alongside Western learning.

By these means, Japanese leaders had been able to fashion a uniquely favourable trajectory with which to enter a West-dominated world. But they were not invincible. The war against Russia forced them to turn to lenders abroad. The patriotic emotions it roused at home threatened the oligarchic tenor of Japanese politics. With its new burden of debt, the Japanese economy lurched into deficit. It risked the fate of other semi-industrial economies in the same position: monetary contraction (Japan was on the gold standard), a reduced demand for its domestic manufactures, and increased dependence upon raw-material exports.

131

Nor was the victory of 1905 secure beyond doubt. Russia was doubling the Trans-Siberian Railway, the iron artery of its eastern empire. In China, meanwhile, Yuan Shih-k'ai, a protégé of Li Hung-chang and an adversary of Japan since his days as China's emissary in Korea in 1884, had imposed his control as a âstrongman' president. By late 1913 he enjoyed the support of the leading Western powers as an effective ruler with whom to do business, a status that Japan had grudgingly to accept.

132

But timing is everything. Before these developments could undermine Japan's newfound regional preeminence, the European war upset all predictions.