After Tamerlane (55 page)

Authors: John Darwin

*

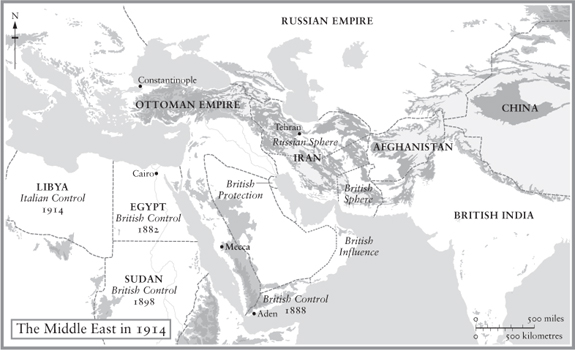

East Asia was not the only âunfinished business' of a Europe-centred global colonialism. In the Middle East, the Ottoman Empire had proved surprisingly resilient, despite its near-catastrophe in 1875â8. Sultan Abdul Hamid II pressed ahead with Ottoman self-strengthening, exploiting the great powers' inability to agree on a partition that might have felled his authority. State power grew wider and reached deeper. Schools and gendarmes carried it into the localities. An expanding bureaucracy drewin local elites.

133

Ottoman rule was gradually made more effective in the Arab provinces.

134

The Hejaz Railway between Aleppo and Medina tightened Ottoman control over the Red Sea coast and the great centres of pilgrimage. Along the âArab shore' of the Persian Gulf, Ottoman forces made their presence felt in the region of El Hasa, between Kuwait and Bahrein (where British influence was growing). Meanwhile the Ottoman economy was benefiting from the booming trade in rawmaterials after 1896.

135

Although modern mechanized factories were few and far between, the manufacture of cottons and carpets also grewsteadily.

136

As a purely Asian state, the Ottoman Empire might have been able to combine its diplomatic leverage and cultural cohesion to win the time it needed to build a stronger state structure and a stronger economy. But in its western half it was dangerously exposed to the unremitting pressure of local European nationalisms, directly expressed as religious and ethnic struggle. After 1878 the Ottomans had clung on to a substantial part of their European empire. Here, in Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, Rumelia and Thrace, over half the population was Muslim.

137

But every attempt to consolidate Ottoman authority was bound to harden ethnic and religious divisions and redouble the antagonism of the subject peoples, both Christian and Muslim. Thus Muslim Albanians fiercely resisted their threatened loss of local autonomy. In the late 1890s, ethnic violence in Crete embroiled the Ottomans in war with Greece and, after great-power intervention, brought the practical end of their rule on the island. By 1908 it seemed that local revolt and foreign interference had brought the key region of Macedonia (the strategic pivot of Ottoman Europe) to the verge of independence. To militant âYoung Turks' in the Ottoman army and bureaucracy, âMacedonia's independence means the loss of half of the Ottoman Empire and⦠its complete annihilation.'

It would drive the Ottoman frontier back to Constantinople, and force the capital out of Europe. âThe Macedonian Question is the Question of the Existence of the Turks.'

138

It was no coincidence that the political coup of 1908 to sideline the sultan and rebuild the empire round an ethnic Turkish core was launched from Salonica. In the short term at least, it did little good. Later that year, Bosnia (technically still an Ottoman territory) was annexed unilaterally by AustriaâHungary. By 1911 the Ottomans were at war with Italy in a hopeless struggle to keep control of Libya. The following year, Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece and Montenegro seized the chance to liquidate what remained of the Ottoman Europe. After a second war between the victor states, a fragile peace settled over the Balkans. The Ottoman government had kept control of the Straits (the site of its imperial capital). But its shattered prestige and signs of resistance in the Arab provinces to âTurkification' made it seem more dependent than ever on the twists and turns of great-power diplomacy if it was to escape dissection.

By 1914, Iran (still usually called Persia) seemed still closer to the brink. Even under a forceful shah like Nasir al-Din, adept at managing the tribal, linguistic, religious and social divisions that seamed Iranian society, the goal of strengthening the state had been elusive. Granting foreign concessions to raise more revenue was deeply unpopular with bazaar merchants and

ulama

, the commercial and religious elites. After Nasir was murdered in 1896, his successor as shah, Muzaffar al-Din, pursued the search for newfunds with even more urgency. He appointed a Belgian to take charge of the customs, the main source of state revenue. A large loan was contracted with Russia, secured on the customs revenues of the Caspian ports. A concession was granted to a British prospector searching for oil at the head of the Gulf: this was the D'Arcy concession, out of which grew the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, the parent of BP. But the shah was now being caught in a vice. As foreign interests grewlarger, so did foreign influence. As more Iranians travelled abroad, or had contact with Europe, liberal, nationalist and even socialist ideas began to circulate among the elite. An extraordinary florescence of political activity in clubs and societies began to take shape. When Russia was plunged into revolutionary turmoil in 1905, choking off the main outlet for Iranian trade and creating commercial panic, a discontented elite joined forces with the

merchants and clerics and the khans of the great Bakhtiari tribe to bring down the shah in the constitutional revolution of 1906.

139

The results were dismaying. Although the shah was forced to accept the newconstitution (which enshrined Shia Islam as the state religion, as well as creating a parliament), he did so on sufferance. When he staged a coup to recover his power, it badly misfired. But, although the constitution was saved, the damage was done. As rival factions struggled to control the government, the power of the centre began to dissolve. Provincial governors and tribal leaders, with their private armies, became the real source of authority. âIn modern Persia,' a Qashqai tribesman told a British consul, âthe rifle is the sceptre and⦠every rifleman is a shah.'

140

It was only a short step to seek the protection of the chief foreign powers. After 1907, when Russia and Britain agreed to divide Iran between them into three spheres of influence â one Russian, one neutral, one British â this trend became stronger. Russian troops intervened in the north to stop the fighting between the shah's supporters and foes. In 1911 they forced the dismissal of the American expert hired to restore Iran's finances to order. Instead, under Russian protection, the provincial authorities diverted taxation and secured practical freedom from their nominal masters in Tehran. On the eve of the First World War, the British angrily complained that northern Iran had become a Russian âpolitical protectorate', enforced by a garrison of

17,000

men. âNorthern Persia was being governed as Russian province,' said the British ambassador.

141

The reply from St Petersburg was coldly dismissive. The Tehran government was made up of demagogues, with âultra-nationalist ideas not in accordance with the cultural or ethical level of these spheres'.

142

Had Iran been strangled, as the dismissed American expert alleged?

143

Almost, but not quite. Despite the drastic decentralization of power that the revolution had brought, and which the foreign presence encouraged, it seems likely that the sense of Iran's national identity had actually been strengthened since the 1890s among the secular educated class as well as the clerics. Yet it was hard to see how an escape could be made from the virtual partition being imposed by the Russians with British complicity. Unless, that is, something happened to disturb the geopolitical setting and slacken the grip that the outside powers had fixed on the country.

These conditions in the âNear East' (the European name for a vast region that also included Iran) and East Asia were the clearest evidence that a global order under the management of the European great powers, and designed to serve their imperial interests, remained at best a work in progress. In the Outer World beyond Eurasia, the Europeans had partitioned with gusto. Here it had proved relatively easy to attach â by coercion or cooperation â less-developed economies to the commercial and industrial heartland of the North Atlantic basin. Here too they had imposed their rule and fashioned âneo-Europes' in an astonishing burst of demographic imperialism. But in the âOld World' of Eurasia it had proved much harder to absorb Asian states and cultures into a European âsystem', or even to agree upon a colonial share-out. This was the vast uneasy borderland of Europe's global colonialism. If the Europeans fell out among themselves, and their âworld economy' lost its magnetic power, they might face a rebellion against their worldwide pre-eminence. This test of their power was not long in coming.

Towards the Crisis of the World, 1914â1942

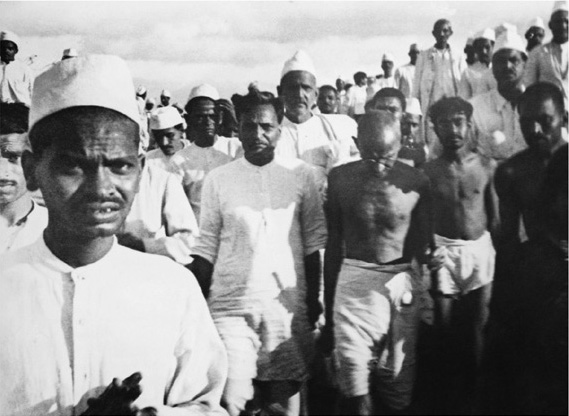

7. Gandhi's âsalt march' to the sea, 1930

Before 1914 there had been warning signs that a global imperial order offered no guarantee of universal peace and prosperity. East Asia's future as a sphere of Western influence was at best uncertain. The European great powers had squabbled irritably over the share-out of territory and influence in North Africa and the Middle East. The size and scale of the American economy raised awkward questions over howfar American interests could be accommodated in a global economy centred on London and partitioned spatially between the European colonial powers. The frantic pace at which international trade and investment had been growing seemed to be easing off. Social unrest in Europe's industrial economies threatened to clip the wings of the great-power governments and to rein in their global ambitions and strategies. But, before the influence of any of these changes could be felt internationally, world politics were transformed by a volcanic explosion, beginning in Europe but rapidly spreading to engulf every important state across the breadth of Eurasia.

The First World War brought a violent end to the experiment in more or less cooperative imperialism among the six great powers (Britain, Russia, Germany, France, the United States and Japan). It reopened the question of a global partition half settled half shelved before 1914. It advanced a newconception of international society, theoretically (if not practically) at odds with the ever-wider extension of colonial rule. It opened a huge ideological fissure between one old imperial power, Russia, and the other great powers. It drove a massive wedge into the international economy: closing off trade routes, blocking currencies and payments, creating artificial shortages and siege-type economies. It forced a mobilization of colonial resources, including manpower, that bred a sharp reaction among colonial peoples, resentful of newburdens and rules that broke the old âbargain' of colonial politics. It tore apart the myth of Europe's uniquely progressive culture, loosening the grip of older cultural elites and the ideas they had championed.

It was hardly surprising that there was no post-war return to pre-war ânormality'. There was no broad agreement on the rules of international order. The annexations and treaties that formed the âlegal' basis of the colonial system and its semi-colonial extensions in China and elsewhere were fiercely repudiated by the Bolshevik legatees of the tsarist empire. The United States rejected membership of the new League of Nations, a victors' club to police the post-war settlement. The economic recovery of Europe was heavily delayed by the bitter disputes over reparations for war damage. Europe's social and political stability suffered badly in consequence. Across much of Eurasia â in the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Middle East and parts of East Asia

â the question of who would rule where had to be decided more by force, or the threat of it, than by diplomacy. In the colonial empires (the British Empire especially), nationalist demands for independence or self-rule showed unprecedented tenacity. Sinn Fein in Ireland, the Wafd movement in Egypt, and Gandhi's great ânon-cooperation' campaign in India (1920â22), with its large Muslim component, posed a ferocious challenge to British authority and exposed the limits of coercion as a method of rule. The mood of revolt was not simply political. There and elsewhere (most notably in China) it was also expressed in the demand for newcultures, authentically local but aimed (by mass consumption) to bind leaders and people in more intense solidarity against the outside (and imperial) world.