After Tamerlane (49 page)

Authors: John Darwin

The three decades after 1880 were just as critical to Russia's prospects as a global power. Conventional histories of the late tsarist period like to emphasize the failures of the old regime. Peasant discontent, a weak middle class, over-hasty industrialization and an âobsolete' autocracy are the usual culprits. Tsarism was a revolution waiting to happen. But too much emphasis upon decline and decay makes for a myopic viewof Russia's modern history. Despite the catastrophic impact of war and revolution in the time of troubles between 1917 and 1921, the Russian Empire did not fall apart. Moreover, it was able to stage an astonishing recovery in the mid- 1940s, to reach a zenith of power that the most visionary official would have dismissed as absurd in the tsarist era.

This is all the more surprising because so much of Russia's Eurasian empire was little more than a shell before 1880. The imperial conquest of Muslim Central Asia was only just under way. The Russian sphere in North East Asia had been greatly enlarged at China's expense by the Aigun and Peking treaties of 1858â60. But the Russian presence across most of this vast region was little more than notional. The 1860s reforms had made no immediate difference to Russia's material strength: indeed the setbacks abroad in 1877â8 (when Russian hopes of a quick military victory over the Ottoman Empire were thwarted) and political dissidence at home suggested quite the opposite. The

modernization of the serf economy had hardly begun. Given the speed of change elsewhere in the world â the flows of investment, the rising volume of trade, the onward rush of technology â Russia's claim to remain in the front rank of powers looked precarious at best. Oppression and muddle seemed (to most foreign observers) the dominant feature of the tsarist system. The result was a policy of âalternate bravado and vacillation', said a young George Curzon with all the confidence of an Indian-viceroy-to-be.

38

Yet Russian power was growing all the same. Industrialization had been slowto arrive, but by the 1890s it was expanding fast. By the end of the century, Russia's output of coal was some fifty times greater than in 1860, the production of steel two thousand times greater.

39

Both had doubled again by 1913. Russian exports rose sharply â from around £ 55 million (the average for 1881â5) to almost £ 100 million (1901â6).

40

The Ukraine was developed as a great producer of wheat. Odessa, the city founded by Catherine the Great on the shores of the Black Sea, was the great emporium of this new grain trade. Once Russia's alliance with France had been formalized (by 1894), a tide of French loans poured in to modernize Russia.

41

The great railway projects to link Russia's heartland with Central Asia (the OrenburgâTashkent Railway) and the Pacific (the Trans-Siberian) could now be completed. As the railways drove forward, behind them followed an army of settlers, land-hungry peasants from the overcrowded villages of European Russia. These Russian colonists, farmers and railway-men, spread out south and east to form the most durable element of Russia's Asian power.

42

By 1914, more than 5 million Russians had crossed the Urals into Siberia, and thousands more had settled in the old Muslim khanates in Russian Central Asia.

43

In this piecemeal way, the tsarist regime had put into place before the First World War almost all the key elements of Russia's modern imperial system. It had kept its grip on rebellious Poland, its salient in Europe, the defensive bastion of the Russian heartland and a lever of influence in great-power diplomacy. The Ukraine had been made into a milch cow of wealth, the engine of Russia's growing commercial influence in the Black Sea region, and the dynamo of the new wheat-export economy. Ukrainian prosperity, and the railway system, helped strengthen Russia's hold on the Caucasian borderlands,

the road bridge to the Middle East, and (from the opposite point of view) the great defensive outwork of the Volga valley â Russia's Mississippi. Before 1914, the oilfields found round Baku on the Caspian had added a newdimension to the Caucasus's strategic value. With railways, settlers, a new cotton economy and a strong military presence, Central Asia had been firmly locked into its colonial role guarding the south-east door into Russia's Eurasian empire. Its trade was carefully sealed off and made a Russian monopoly.

44

And, as Siberia was colonized and its communications improved, Russia's fragile grasp on the Pacific coast was decisively strengthened.

45

Not even the disaster of the Russo-Japanese War (1904â5), when Russian designs on Korea and Manchuria were brutally crushed (there had been a plan to infiltrate Korea with Russian soldiers disguised as lumberjacks), could break Russia's claim to be a Pacific power or roll back its expansion into North East Asia.

46

Thus, for all the brittleness of its imperial system, its technical backwardness, economic fragility and weak cultural magnetism,

47

Russia had more than kept pace with the rival world states. It had followed its own distinctive trajectory into global colonialism.

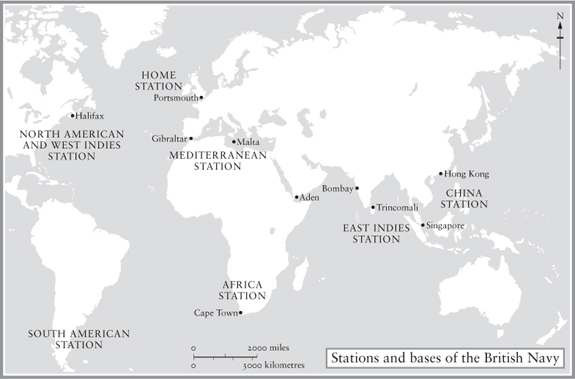

In 1880, Britain had some claim to be the leading world state â perhaps the only one to have possessions and interests in every part of the world. Its huge archipelago of colonies and spheres ran from western Canada to South Africa, from Suez to Hong Kong. Much of this empire had been built up rapidly since the 1830s, and much was lightly peopled and barely developed. Across vast areas, British claims to influence existed only by default, since no other power had any presence at all. But after 1880, as the world âfilled up', influence by default was no longer an option. The British were pushed into formalizing their claims, and sometimes backing them up by displays of force. As ever more of the world was partitioned, they acquired fresh sets of potentially troublesome neighbours, newfences to maintain, and a newneed for vigilance. The result was paradoxical. Although the British Empire became larger and larger, the diplomats and strategists charged with protecting it became more and more anxious. Because the British had so much territory scattered round the world, they seemed always at odds with everyone else. The British

Empire was like a huge giant, moaned a senior official, âwith gouty fingers and toes stretching in every direction'. The minute it was approached by anyone else, the giant would scream with fear at the expected pain.

48

It was a poor recipe for diplomatic harmony. The strategists were just as nervous. They saw Britain's naval power and small professional army as dangerously overextended. Some of the most acute observers wondered whether the spread of railways had turned the tables on the great sea power. Perhaps the balance of advantage nowlay with the rulers of an impregnable land mass â like Russia, the âinland tyranny' â safe from British chastisement.

Fears like these reached a pitch of intensity during the South African War, which exposed an embarrassing deficit in British military prowess. Even more worrying was the risk that Britain's great-power rivals would seize a golden opportunity to put a squeeze on British interests in other parts of the world: in the Middle East, in China, and perhaps even by threatening an invasion of India across its north-west frontier. This fearful prospect set off a frenzy in military planning, one of the conclusions of which was that the British army would need to buy every camel in Asia to supply the front line. For one of the reasons we have already considered â the fear of disturbing the European balance â the other great powers decided against an anti-British coalition. But the sense of crisis had been real in London. It produced a major rethink in naval strategy, and the decision to build a new modern fleet. It brought an alliance with Japan (in 1902) to help guard British interests in East Asia.

49

In 1904 and 1907 it led to ententes with first France and then Russia â agreements that drew Britain into an informal alliance in Europe's great-power politics.

50

In the newera of âworld politics' after 1880, Britain seemed to have suffered a relative decline. But by any standard its overall position remained immensely strong. There were very few places where a single power could seriously damage its interests. The great exception (since an American invasion of Canada seemed no longer conceivable) was a Russian invasion of Afghanistan, and the threat that that would pose to British power in India. It was extremely unlikely that a combination of powers would be allowed by the others to aggrandize themselves at Britain's expense â even if they were to risk the attempt.

Furthermore, on several counts, the British themselves seemed to be getting richer and stronger. They had profited more than anyone else from the huge expansion of international trade. Their foreign investments alone were to double in size between 1900 and 1913. They had a massive balance-of-payments surplus from their invisible exports, and could easily afford the enormous cost of a huge new navy. Their settler colonies â a great manpower reserve of more than a million men of military age â were now growing rapidly. So also was India, the barrack and war chest of their empire in Asia. Their commercial imperium of overseas enterprises in banking, insurance, shipping, railways, telegraphs, mines and plantations dwarfed all its rivals. In the event of attack, the vast reserve power of their economic assets could be wheeled into action while the enemy was crushed by the constrictor-like grip of a naval blockade. That at least was the plan.

After 1904, it was mainly from Germany that the British expected such a threat to arise. Like the United States, Germany was a newcomer in great-power diplomacy, crashing on to the scene after 1870 with the defeat of France and the unification of the German states into a semi-federal âempire' under the Prussian monarchy. Germany seemed to have both the means and, after 1900, the ambition to practise

Weltpolitik

â to become a world state. The platform for this was the rocketing growth of the German economy: Germany's national product grewthreefold between 1873 and 1913.

51

Its industrial output was especially strong in the new manufacturing sectors of chemical and electrical goods. By 1900, Germany had an excellent railway system and the largest population of any European state except Russia.

52

Good communications, a great industrial base and a large population made Germany's conscript army the most efficient in Europe, and Germany itself Europe's greatest military power. In the mid- 1880s, Bismarck had used these growing assets to collect some trophy colonies in the great African partition (and one or two others in the South Pacific). But all the signs are that he thought them worthless.

53

His successors after 1890 were not so sure. If China was partitioned (as seemed not unlikely), the Pacific boxed up into maritime spheres and the Ottoman Empire dismantled (another likely prospect by the mid- 1890s), then Germany should claim a share that

reflected its status and economic potential. If the future was to be a silent Darwinian struggle for survival or supremacy in a closed world system, any other course would be a virtual abdication.

The aggressive manner with which the Germans sought their âplace in the sun' has become a historical cliché. Yet what is really striking about the

Weltpolitik

they pursued from the late 1890s was how half-hearted it was.

54

In the various colonial squabbles in which they became embroiled â over Samoa, Morocco (twice), West Africa and the Baghdad railway to the Persian Gulf â the Germans backed off or accepted a compromise. There were good reasons for this. Although Germany's overseas trade was increasingly active (for example in Latin America),

55

its economic interests remained chiefly in Europe (as did German foreign investment). German military power was a European phenomenon. Without a deep-sea navy, it would have to stay that way. Yet when Berlin began building an ocean-going fleet, it immediately ran into the opposition of Britain. After 1909 it was crystal-clear that the British would out-build any German navy, no matter what the cost. And, from their great base in the Orkneys, they could bottle it up and prevent its escape from its North Sea ports.

There was a brutal logic to the German position. Germany's strength lay in Europe, where there were millions of ethnic Germans still beyond its frontiers, an old tradition of German commercial and financial pre-eminence in Eastern and Central Europe, and a set of would-be client states, including the Austro-Hungarian Empire, technically still one of the great powers of Europe. âIf the world across the seas should consolidate itself under England's hegemony,' said the colonial propagandist Carl Peters, âthere can be nothing but a United States of Europe to preserve for the old world its supremacy.'

56

Peters's meaning was clear. The achievement of a German hegemony in Europe (at the expense of Russia, France and Britain) would more than compensate for the lack of an empire on the British model. It would also smash the geopolitical props on which global colonialism had been built thus far, and open the way for a new global partition in Germany's favour. But to gain such a hegemony by force was much too dangerous a plan to be adopted lightly, or even debated openly by those who made policy (one of the reasons why the debate among historians over German war guilt has been so inconclusive). Up to

1914, it remained an imaginary prize that unforeseen circumstances might suddenly offer.