A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future (23 page)

Read A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Leadership, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Success

“The opposite of play isn’t work. It’s depression. To play is to act out and be willful, exultant and committed as if one is assured of one’s prospects.”

—

BRIAN SUTTON-SMITH,

professor of education

(emeritus), University of

Pennsylvania

Like its five sibling senses, Play is emerging from the shadows of frivolousness and assuming a place in the spotlight.

Homo ludens

(Man the Player) is proving to be as effective as Homo sapiens (Man the Knower) in getting the job done. Play is becoming an important part of work, business, and personal well-being, its importance manifesting itself in three ways: games, humor, and joyfulness. Games, particularly computer and video games, have become a large and influential industry that is teaching whole-minded lessons to its customers and recruiting a new breed of whole-minded worker. Humor is showing itself to be an accurate marker for managerial effectiveness, emotional intelligence, and the thinking style characteristic of the brain’s right hemisphere. And joyfulness, as exemplified by unconditional laughter, is demonstrating its power to make us more productive and fulfilled. In the Conceptual Age, as we’ll see, fun and games are not just fun and games—and laughter is no laughing matter.

Games

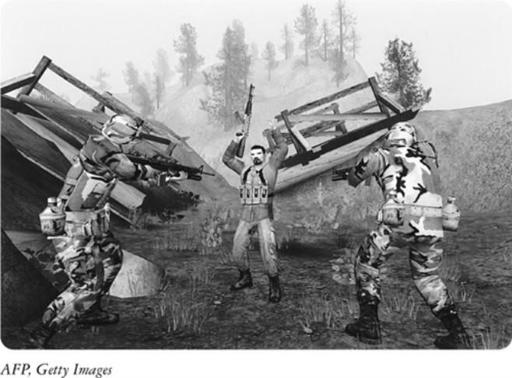

Here’s a screen shot from a popular video game called

America’s Army:

When you play this game, you navigate a treacherous environment, trying to knock off bad guys while avoiding getting whacked yourself. You earn points for nailing opposing soldiers and for helping your side elude harm, a format and structure similar to most games in this genre. So here’s a question: Which company makes the game? Nintendo? Sega? Electronic Arts? Nope. The organization that created, manufactured, and distributed

America’s Army

is . . . America’s Army, the United States military.

A few years ago Colonel Casey Wardynski, a West Point professor who specializes in military manpower, was working on ways to boost recruiting for the armed forces, which had fallen to dismal levels. Because the draft had ended in the 1970s and the size of the military had shrunk after the end of the Cold War, potential recruits knew much less than previous generations about what it was like to serve in the armed forces. While chewing on this problem, Wardynski noticed that the cadets he was teaching at West Point were obsessed with video games. And in a flash of right-brain inspiration, he glimpsed a possible solution.

What if, Wardynski wondered, the military tried reaching young people where they live—on Sony PlayStations, Microsoft Xboxes, and personal computers? Since gauzy television ads and person-to-person persuasion couldn’t give recruits a feel for the reality of military service, perhaps the Army could, as Wardynski put it, substitute “virtual experiences for vicarious insights” by creating a video game. He presented his plan to the Pentagon brass, which, concerned about a shortfall in personnel, was willing to try anything. They gave Wardynski a healthy budget, and he began formulating a game that he thought would convey the substance of Army life while also being engaging and challenging to play. Over the next year, he and a team from the Naval Postgraduate School, with the help of several programmers and artists, built

America’s Army

and released it for free on the GoArmy.com Web site on July 4, 2002. That first weekend, demand was so great that it crashed the Army’s servers. Today the game, which is also distributed on disk at recruiting offices and in gaming magazines, has more than two million registered users. On a typical weekend nearly a half-million people sit in front of computer screens, maneuvering through simulated military missions.

5

America’s Army

says it’s different from many other martial games because of its emphasis on “teamwork, values, and responsibility as a means of achieving the goals.” Players go through basic training, advance to multiplayer games where they work in small units, and, if they’re successful, move on to become Green Berets. Most of the missions are team endeavors—rescuing a prisoner of war, protecting a pipeline, thwarting a weapons sale to terrorists. Players earn points not only for killing enemies but also for protecting other soldiers and for completing a mission with everyone in the unit still alive. If you try something stupid—for instance, gunning down civilians or ignoring orders—you can end up in a virtual Leavenworth prison or find yourself banished from the game altogether. And like any producer with a hit on its hands, the Army has produced a sequel—a new edition of the game called

America’s Army: Special Forces.

This ought to throw a bucket of cold water on the overheated belief that Play is an aptitude only for the hackey-sack set. The reality is more surprising: just as General Motors is in the art business, the U.S. military is in the game business. (Indeed, had the military sold the game at a price comparable to other video games, the Army would have earned about $600 million in the first year.

6

)

“Games are the most elevated form of investigation.”

—

ALBERT EINSTEIN

The military’s embrace of video games is just one example of the influence of these games. From their humble beginnings thirty years ago, when

Pong,

one of the very first, made its appearance in arcades, video games (that is, games played on computers, on the Web, and on dedicated platforms such as PlayStation and Xbox) have become a booming business and a prominent part of everyday life. For example:

• Half of all Americans over age six play computer and video games. Each year, Americans purchase more than 220 million games, nearly two games for every U.S. household. And despite the common belief that gaming is a pastime that requires a Y chromosome, today more than 40 percent of game players are women.

7

• In the United States, the video game business is larger than the motion picture industry. Americans spend more on video games than they do on movie tickets. On average, Americans devote seventy-five hours a year to playing video games, double the time they spent in 1977 and more time than they spend watching DVDs and videos.

8

• One game company, Electronic Arts, is now part of the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. In 2004, EA earned nearly $3 billion, more than the combined revenue of the year’s ten top-grossing movies. Nintendo’s

Mario

series of video games has earned more than $7 billion over its lifetime—double the money earned by all the

Star Wars

movies.

9

Still, unless they live in a home with thumb-twitching teenagers, many adults haven’t fully comprehended the significance of these games. For a generation of people, games have become a tool for solving problems as well as a vehicle for self-expression and self-exploration. Video games are as woven into this generation’s lives as television was into that of their predecessors. For example, according to several surveys, the percentage of American college students who say they’ve played video games is 100.

10

On campuses today you’d sooner find a short-tailed tree frog taking calculus than an undergrad who’s never fired up

Myst, Grand Theft Auto,

or

Sim City.

As two Carnegie Mellon University professors write, “We routinely poll our students on their experience with the media, and typically we cannot find a single movie that all fifty students in the course have seen (only about a third have usually seen

Casablanca,

for instance). However, we typically find at least one video game that every student has played, like

Super Mario Brothers.”

11

Some people—many of them members of my own fortysomething geezer set—tend to despair over such information, fearing that each minute spent wielding a joystick represents a step backward for individual intelligence and social progress. But that attitude misunderstands the power of these games. In fact, James Paul Gee, a professor at the University of Wisconsin and author of

What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy,

argues that games can be the ultimate learning machine. “[Video games] operate with—that is, they build into their designs and encourage—good principles of learning, principles that are better than those in many of our skill-and-drill, back-to-basics, test-them-until-they-drop schools.”

12

That’s why so many people buy video games, and then spend fifty to one hundred hours mastering them, roughly the length of a college semester.

13

As Gee writes, “The fact is when kids play video games they can experience a much more powerful form of learning than when they’re in the classroom. Learning isn’t about memorizing isolated facts. It’s about connecting and manipulating them.”

14

Indeed, a growing stack of research is showing that playing video games can sharpen many of the skills that are vital in the Conceptual Age. For instance, an important 2003 study in the journal

Nature

found an array of benefits to playing video games. On tests of visual perception, game players scored 30 percent higher than nonplayers. Playing video games enhanced individuals’ ability to detect changes in the environment and their capacity to process information simultaneously.

15

Even doctors can benefit from a little time at the GameCube. One study found that physicians “who spent at least three hours a week playing video games made about 37 percent fewer mistakes in laparoscopic surgery and performed the task 27 percent faster than their counterparts who did not play.”

16

Another study even found that playing video games at work can boost productivity and enhance job satisfaction.

17

“Play will be to the 21st century what work was to the last 300 years of industrial society—our dominant way of knowing, doing and creating value.”

—

PAT KANE

,

author of

The Play Ethic

There’s also evidence that playing video games enhances the right-brain ability to solve problems that require pattern recognition.

18

Many aspects of video gaming resemble the aptitude of Symphony—spotting trends, drawing connections, and discerning the big picture. “What we need people to learn is how to think deeply about complex systems (e.g., modern workplaces, the environment, international relations, social interactions, cultures, etc.) where everything interacts in complicated ways with everything else and bad decisions can make for disasters,” says Gee. Computer and video games can teach that. In addition, the fastest growing category of games isn’t shooter games like

America’s Army

but role-playing games, which require players to assume the identity of a character and to navigate a virtual world through the eyes of that figure. Experiences with those simulation games can deepen the aptitude of Empathy and offer rehearsals for the social interactions of our lives.

What’s more, games have begun to reach the medical field. For example, children with diabetes can now use GlucoBoy, which hooks up to a Nintendo Game Boy, to monitor their glucose levels. And at California’s Virtual Reality Medical Center, therapists are treating phobias and other anxiety disorders with video games that simulate driving, flying, heights, tight spaces, and other fear-inducing situations.

To be sure, games aren’t perfect. Some evidence points to a correlation between game-playing and aggressive behavior, though it’s unclear whether a causal link exists. And certain games are utter time-wasters. But video games are much more valuable than hand-wringing parents or family-values moralists would want you to believe. And the aptitudes players are mastering are especially well suited to an age that relies on the right side of the brain.

Along with being an avocation of millions, gaming is becoming a vocation for hundreds of thousands—and an especially whole-minded vocation at that. The ideal hire, says one game-industry recruiter, is someone who can “bridge that left brain-right brain divide.”

19

Companies resist segregating the disciplines of art, programming, math, and cognitive psychology and instead look for those who can piece together patches of many disciplines and weave them together into a larger tapestry. And both the maturation of games and the offshoring of routine programming work to Asia are changing the emphasis of the gaming profession. As one gaming columnist writes: “Changes in the way games are built indicate less of a future demand for coders, but more of a demand for artists, producers, story tellers and designers. . . . ‘We’ve moved away from relying simply on code,’ said [one game developer]. ‘It’s become more of an artistic medium.’ ”

20