A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future (18 page)

Read A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Leadership, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Success

“The guy who invented the wheel was an idiot. The guy who invented the other three, he was a genius.”

—

SID CAESAR

Both academic studies and firsthand observations are showing that pattern recognition—understanding the relationships between relationships—is equally important for those who aren’t intent on building their own empire. Daniel Goleman writes about a study of executives at fifteen large companies: “Just one cognitive ability distinguished star performers from average: pattern recognition, the ‘big picture’ thinking that allows leaders to pick out the meaningful trends from a welter of information around them and to think strategically far into the future.”

15

These star performers, he found, “relied less on deductive, if-then reasoning” and more on the intuitive, contextual reasoning characteristic of Symphony. The shifting terrain is already prompting some archetypal L-Directed workers to recast who they are and what they do. One example: Stefani Quane of Seattle, who calls herself a “holistic attorney,” dedicated to taking care of your will, trust, and family matters by viewing them in context rather than isolation, and examining how your legal concerns relate to the entirety of your life.

More and more employers are looking for people who possess this aptitude. Sidney Harman is one of them. The eightysomething multimillionaire CEO of a stereo components company says he doesn’t find it all that valuable to hire MBAs. Instead,

I say, “Get me some poets as managers.” Poets are our original systems thinkers. They contemplate the world in which we live and feel obliged to interpret and give expression to it in a way that makes the reader understand how that world turns. Poets, those unheralded systems thinkers, are our true digital thinkers. It is from their midst that I believe we will draw tomorrow’s new business leaders.

16

Business and work, of course, are far from the only places where seeing the big picture is helpful. This aspect of Symphony has also become crucial for health and well-being. Take the growing appeal of integrative medicine, which combines conventional medicine with alternative and complementary therapies, and its cousin, holistic medicine, which aims to treat the whole person rather than the particular disease. These movements—grounded in science but not dependent solely on science’s often L-Directed approach—have achieved mainstream recognition, including their own branch of the National Institutes of Health. They move beyond the reductionist, mechanistic approach of conventional medicine toward one that, in the words of one physicians’ professional association, integrates “all aspects of well-being, including physical, environmental, mental, emotional, spiritual and social health; thereby contributing to the healing of ourselves and our planet.”

17

The capacity to see the big picture is perhaps most important as an antidote to the variety of psychic woes brought forth by the remarkable prosperity and plentitude of our times. Many of us are crunched for time, deluged by information, and paralyzed by the weight of too many choices. The best prescription for these modern maladies may be to approach one’s own life in a contextual, big-picture fashion—to distinguish between what really matters and what merely annoys. As I’ll discuss in the final chapter, this ability to perceive one’s own life in a way that encompasses the full spectrum of human possibility is essential to the search for meaning.

O

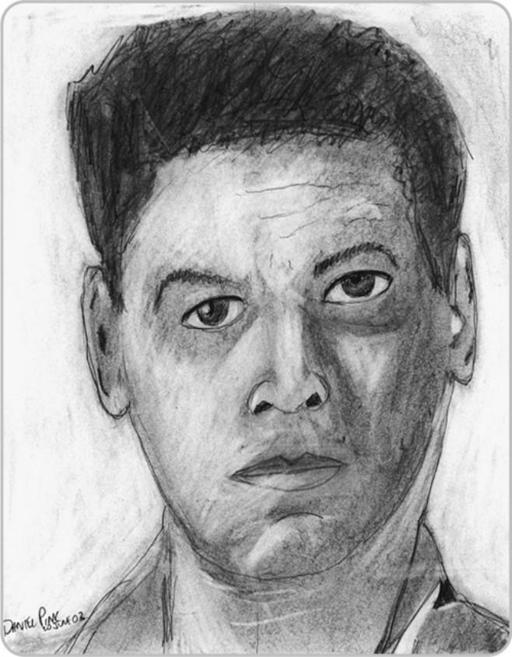

N THE FINAL DAY

of drawing class, we approach the week’s crescendo. After lunch, we each tape our small mirrors to the wall. We position our chairs about eight inches away and begin to draw our self-portraits once again. Bomeisler warns us of the perils lurking in the looking glass. “We’ve used the mirror to prepare ourselves to face the world. Clear your mind of any thoughts you’ve had about that and concentrate on the shapes, the lights, and the relationships,” he says. “You want to see what your face looks like on this particular day in this particular place.”

At lunch, I swap my glasses for contact lenses so I won’t have to draw the shadows cast by my spectacles. Given my performance on the first self-portrait, I’ll take any edge I can get. I begin with my eyes—really looking at them, seeing what shape they are, where the color ends and the whites of my eyeballs begin, realizing that the width between my two eyes is exactly the same as the width of each individual eye. My nose, though, gives me fits—in part because I keep

thinking

of a nose instead of just seeing what’s plain on my face. I skip that part—and for the longest time, my self-portrait has a big empty spot in the center, a Venus de Milo of proboscises. When I get to the mouth, I draw and redraw it nine times until I get it right because the early renditions keep looking like that Magikist sign. But the shape of the head comes easily because I just erase the negative space around it.

To my amazement, what emerges on the sketchpad begins to look a little like me on that particular day in that particular place. Bomeisler checks in on my progress, touches my shoulder, and whispers, “Fantastic.” I almost believe he means it. And as I pencil in the finishing touches, I experience a tiny hint of the kind of feeling a terrified mother must have after she’s lifted a Buick off her child and wonders where her strength came from.

When I’m done, after seeing the relationships and integrating those relationships into the big picture, this is me.

Listen to the Great Symphonies.

Listening to symphonies, not surprisingly, is an excellent way to develop your powers of Symphony. Here are five classics the experts recommend. (Of course, particular recordings—with different conductors and orchestras—will vary in style, interpretation, and sound. )

Beethoven’s 9th Symphony—

One of the most famous symphonies of all time, Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” is always a treat. I’ve found that on each listening something new surfaces—in part because the context in which I’ve listened alters and shapes the meaning.

Mozart’s Symphony No. 35, “Haffner Symphony”—

Notice how Mozart brings in the woodwinds at the end to create a whole that dramatically surpasses the sum of the parts.

Mahler’s 4th Symphony in G Major—

I doubt that inspiration was Mahler’s aim, but his 4th Symphony always sounds inspiring to me.

Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture—

You’ve heard this one many times before. But next time, get a recording that uses actual church bells and cannons—and listen carefully to how the components fit together.

Haydn’s Symphony No. 94 in G Major, “Surprise”—

To master the aptitude of Symphony, you must be open to surprise. When you listen to this, marvel at how Haydn uses surprise to broaden and deepen the music.

Hit the Newsstand.

One of my favorite exercises in conceptual blending is the “newsstand roundup.” If you’re stymied on how to solve a problem, or just want to freshen your own thinking, visit the largest newsstand you can find. Spend twenty minutes browsing—and select ten publications that you’ve never read and would likely never buy. That’s the key: buy magazines you never noticed before. Then take some time to look through them. You don’t have to read every page of every magazine. But get a sense of what the magazine is about and what its readers have on their minds. Then look for connections to your own work or life. For instance, when I did this exercise, I figured out a better way to craft my business cards thanks to something I saw in

Cake Decorating—

and came up with a new idea for a newsletter because of an article in

Hair for You.

Warning: your spouse might give you uncomfortable looks when you come home toting

Trailer Life, Teen Cosmo,

and

Divorce Magazine.

Draw.

A great way to expand your capacity for Symphony is to learn how to draw. As I discovered myself, drawing is about seeing relationships—and then integrating those relationships into a whole. I’m partial to the Betty Edwards approach, because it proved so valuable to me. About a dozen times a year, Brian Bomeisler (and other Edwards disciples) teach courses like the one I took. If you can spare the time, the five-day workshop is well worth the investment. If you can’t, Edwards and Bomeisler have a

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

video. And Edwards’s classic book,

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain,

is available at most booksellers.

(More info:

www.drawright.com

)

For those of you with more curiosity than patience, consider playing around with a five-line self-portrait—that is, drawing your self-portrait using only five lines. It’s a great big-picture exercise and plenty of fun. Here’s one of mine:

Keep a Metaphor Log.

Improve your MQ (metaphor quotient) by writing down compelling and surprising metaphors you encounter. Try it for a week and you’ll understand the power of this exercise. Keep a small notebook with you and scribble when you read a newspaper columnist write that pollsters have “colonized” the minds of our leaders—or when your friend says, “I don’t feel rooted.” You’ll be amazed. When I last kept a log, I came upon such an array of metaphors that the world seemed richer and more vivid. It will also inspire you to create your own metaphors in writing, thought, or other parts of your life.

Follow the Links.

Play your own version of six degrees of separation courtesy of the Internet. Choose a word or a topic you find interesting, type it into a search engine, and then follow one of the links. From the initial site you visit, select one of

its

links, and venture on. Repeat this process seven or eight times, always clicking a new link from the site you’re currently viewing. At the end of your journey, reflect on what you learned about your original topic and the diversions you encountered along the way. What did you encounter because of your casual detours that you might otherwise not have found? What patterns or themes (if any) emerged? What unusual connections between seemingly unrelated thinking did you accidentally discover? Following the links is a commitment to learning by serendipity. A variation: Go with pure chance by using a random web site generator like U Roulette

(

www.uroulette.com

)

or Random Web Search (

www.randomwebsearch.com

). Beginning with a site you never would have visited can take you to places you never expected—and enhance your appreciation for the symphonic relationships between ideas.