A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future (10 page)

Read A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Leadership, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Success

—

PAOLA ANTONELLI,

curator of architecture

and design, Museum

of Modern Art

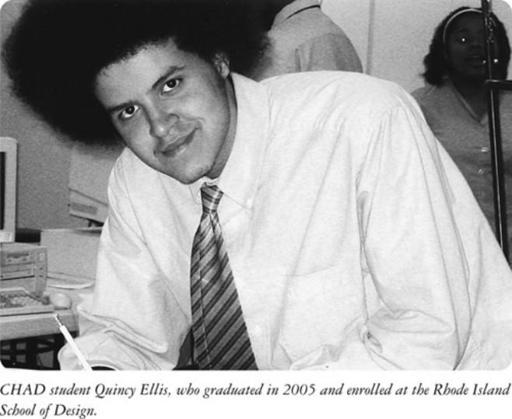

Indeed, merely walking the halls here is inspiring. Student art-work is on display in the lobby. The hallways sport furniture donated by the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. And throughout the school are the works of designers such as Karim Rashid, Kate Spade, and Frank Gehry, some of which are presented in lockers CHAD students have converted into display cases. The students all wear blue button-down shirts and tan pants. The boys also wear ties. “They feel and look like young architects and designers,” the school’s development director, Barbara Chandler Allen, tells me, no small feat in a school where a substantial portion of the student body is eligible for free lunches.

For many of the students, the school is a haven in a harsh world—a place that’s safe and orderly and where the adults care and have high expectations. While the typical Philadelphia public high school has a daily attendance rate of 63 percent, at CHAD it’s 95 percent. Equally revealing is what isn’t here. CHAD is one of the only high schools in Philadelphia without metal detectors. Instead, when students, teachers, and visitors pass through the front door on Sansom Street, they’re greeted by a colorful mural crafted by the American minimalist Sol Lewitt.

Although CHAD is a pioneer, it is not the only school of its kind. Miami’s public school system boasts Design and Architecture Senior High, New York City has the High School of Art and Design. Washington, D.C., has a charter elementary school called the Studio School, where many of the teachers are professional artists. And beyond the elementary and secondary level, design education is positively booming. In the United States, as we learned in Chapter 3, the MFA is becoming the new MBA. In the United Kingdom, the number of design students climbed 35 percent between 1995 and 2002. In Asia, the sum total of design schools in Japan, South Korea, and Singapore thirty-five years ago was . . . zero. Today, the three countries have more than twenty-three design schools among them.

2

At these schools, as at CHAD, many students ultimately might not become professional designers. That’s fine, says deputy principal Christina Alvarez. “We’re building an awareness in students of what design is and how it can affect their lives,” she tells me. “I see the design curriculum as providing a modern version of a liberal arts education for these kids.” No matter what path these students pursue, their experience at this school will enhance their ability to solve problems, understand others, and appreciate the world around them—essential abilities in the Conceptual Age.

The Democracy of Design

Frank Nuovo is one of the world’s best-known industrial designers. If you use a Nokia cell phone, chances are good Nuovo helped design it. But as a younger man, Nuovo had a difficult time explaining his career choice to his family. “When I told my father I wanted to be a designer, he said, ‘What does that mean?’” Nuovo told me in an interview. We “need to reduce the nervousness” surrounding design, Nuovo says. “Design in its simplest form is the activity of creating solutions. Design is something that everyone does every day.”

From the moment some guy in a loincloth scraped a rock against a piece of flint to create an arrowhead, human beings have been designers. Even when our ancestors were roaming the savannah, our species has always harbored an innate desire for novelty and beauty. Yet for much of history, design (and especially its more intimidating cousin, Design) was often reserved for the elite, who had the money to afford such frivolity and the time to enjoy it. The rest of us might occasionally dip our toes into significance, but mostly we stayed at the utility end of the pool.

In the last few decades, however, that has begun to change. Design has become democratized. If you don’t believe me, take this test. Below are three type fonts. Match the font on the left with the correct font name on the right.

1. A Whole New Mind

2. A Whole New Mind

3. A Whole New Mind

a. Times New Roman

b. Arial

c. Courier New

My guess, having conducted this experiment many times in the course of researching this book, is that most of you completed the task quickly and correctly.

*

But had I posed this challenge, say, twenty-five years ago, you probably wouldn’t have had a clue. Back then, fonts were the specialized domain of typesetters and graphic designers, something that regular folks like you and me scarcely recognized and barely understood. Today we live and work in a new habitat. Most Westerners who can read, write, and use a computer are also literate in fonts. “If you are a native of the rain forest, you learn to distinguish many sorts of leaves,” says Virginia Postrel. “We learn to distinguish many different typefaces.”

3

Fonts, of course, are just one aspect of the democratization of design. One of the most successful retail ventures of the last decade is Design Within Reach, a network of thirty-one studios whose mission is to bring great design to the masses. In DWR’s studios and catalogs are the sort of beautiful chairs, lamps, and desks that the wealthy have always purchased but that are now available to wider segments of the population. Target, a family visit to which I described in Chapter 2, has gone even further in democratizing design, often obliterating the distinction between high fashion and mass merchandise, as it has with its Isaac Mizrahi clothing line. In the pages of

The New York Times,

Target advertises its $3.49 Philippe Starck spill-proof baby cup alongside ads for $5,000 Concord LaScala watches and $30,000 Harry Winston diamond rings. Likewise, Michael Graves, whose cerulean toilet brush I purchased during that Target trip, now sells kits that buyers can use to construct stylish gazebos, studios, and porches. Graves, who has designed libraries, museums, and multimillion-dollar homes, is too expensive for most of us to hire to build out the family room. But for $10,000, we might be able to buy one of his Graves Pavilions and enjoy the beauty and grace of one of the world’s finest architects literally in our own backyard.

“Aesthetics matter.

Attractive things work better.”

—

DON NORMAN

,

author

and engineering

professor

The mainstreaming of design has infiltrated beyond the commercial realm. It’s no surprise that Sony has four hundred in-house designers. But how about this? There are sixty designers on the staff of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

4

And while God is bringing artists into the room, Uncle Sam is redoing the room itself. The General Services Administration, which oversees the construction of U.S. government buildings, has a “Design Excellence” program that aims to turn drab federal facilities into places more pleasant to work in and more beautiful to view. Even U.S. diplomats have responded to the age’s new imperatives. In 2004, the U.S. State Department declared that it was abandoning the font it had used for years—Courier New 12—and replacing it with a new standard font that would henceforth be required in all documents: Times New Roman 14. The internal memorandum announcing the change explained that the Times New Roman font “takes up almost exactly the same area on the page as Courier New 12, while offering a crisper, cleaner, more modern look.”

5

What was more remarkable than the change itself—and what would have been unthinkable had the change occurred a generation ago—was that everybody in the State Department understood what the memo was talking about.

Design Means Business/

Business Means Design

The democratization of design has altered the competitive logic of businesses. Companies traditionally have competed on price or quality, or some combination of the two. But today decent quality and reasonable price have become merely table stakes in the business game—the entry ticket for being allowed into the marketplace.Once companies satisfy those requirements, they are left to compete less on functional or financial qualities and more on ineffable qualities such as whimsy, beauty, and meaning. This insight isn’t terribly new. Tom Peters, whom I quoted in the last chapter, was making the business case for design before most businesspeople knew the difference between Charles Eames and Charlie’s Angels. (“Design,” he advises companies, “is the principal difference between love and hate.”) But as with the State Department’s font memo, what’s remarkable about the business urgency of design isn’t so much the idea but how widely held it has become.

“Businesspeople don’t need to understand designers better. They need to be designers.”

—

ROGER MARTIN,

dean,

Rotman School of

Management

Consider two men from separate countries and different worlds. Paul Thompson is the director of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York City. Norio Ohga is the former chairman of the high-tech powerhouse Sony.

Here’s Thompson: “Manufacturers have begun to recognize that we can’t compete with the pricing structure and labor costs of the Far East. So how can we compete? It has to be with design.”

6

Here’s Ohga: “At Sony, we assume that all products of our competitors have basically the same technology, price, performance, and features. Design is the only thing that differentiates one product from another in the marketplace.”

7

Thompson’s and Ohga’s arguments are increasingly borne out on corporate income statements and stock tables. For every percent of sales invested in product design, a company’s sales and profits rise by an average of 3 to 4 percent, according to research at the London Business School.

8

Similarly, other research has shown that the stocks of companies that place a heavy emphasis on design out-perform the stocks of their less design-centric counterparts by a wide margin.

9

Cars are a good example. As I noted in Chapter 2, the United States now has more autos than drivers—which means that the vast majority of Americans who want a car can have one. That ubiquity has brought down prices and boosted quality, leaving design as a key criterion for consumer decisions. U.S. automakers have slowly learned this lesson. “For a long time, going back to the 1960s, marketing directors were more focused on science and engineering, gathering data and crunching numbers, and they neglected the importance of the other side of the brain, the right side,” says Anne Asenio, a design director for GM. And that eventually proved disastrous for Detroit. It took mavericks like Bob Lutz, whom we heard from in Chapter 3, to show that utility requires significance. Lutz famously declared that GM was in the art business—and worked to make designers the equals of engineers. “You need to differentiate or you cannot survive,” says Asenio. “I think designers have a sixth sense, an antenna, that allows them to accomplish this better than other professionals.”

10

Other car companies have shifted gears and headed in this same direction. BMW’s Chris Bangle says, “We don’t make ‘automobiles.’” BMW makes “moving works of art that express the driver’s love of quality.”

11

One Ford vice president says that “in the past, it was all about a big V-8. Now it’s about harmony and balance.”

12

So frenzied are the car companies to differentiate by design that “in Detroit’s macho culture, horsepower has taken a back seat to ambience,” as

Newsweek

puts it. “The Detroit Auto Show . . . might as well be renamed the Detroit Interior Decorating Show.”

13

“Design correctly harnessed can enhance life, create jobs, and make people happy—not such a bad thing.”

—

PAUL SMITH

,

fashion

designer

Your kitchen offers further evidence of the new premium on design. We see it, of course, in those high-end kitchens with gleaming Sub-Zero refrigerators and gargantuan Viking ranges. But the phenomenon is most evident in the smaller, less expensive goods that populate the cabinets and countertops of the United States and Europe. Take the popularity of “cutensils”—kitchen utensils that have been given personality implants. Open the drawer in an American or European home and you’ll likely find a bottle opener that looks like a smiling cat, a spaghetti spoon that grins at you and the pasta, or a vegetable brush with googly eyes and spindly legs. Or just go shopping for a toaster. You’ll have a hard time finding a plain old model, because most of the choices these days are stylized, funky, fanciful, sleek, or some other adjective not commonly associated with small appliances.