A Thousand Sisters (8 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

Finally, a Range Rover with a Women for Women logo pulls up. Christine hops out for an embrace of welcome. “

Karibu!

Welcome!”

Karibu!

Welcome!”

She seems to have changed since we met in the States; perhaps it's because I'm seeing her now in her native environment. Her stature is striking. She carries herself with the dignity of African royalty. The ongoing half-joke at Women for Women is that Christine could someday become the first woman president of DR Congo, and it doesn't seem so much a stretch

.

Her wedding is only a month away and she is in the thick of planning a celebration for five hundred guests.

.

Her wedding is only a month away and she is in the thick of planning a celebration for five hundred guests.

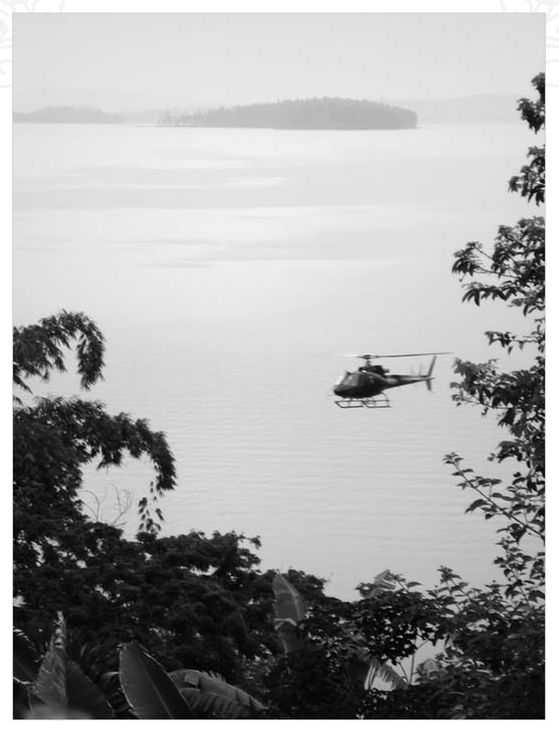

We drive down the tree-lined, paved road that runs above Lake Kivu. Christine explains, “There was a problem with Orchid Safari Club. They

are fully booked with a group for the next few nights, so I've made arrangements for you to stay elsewhere.”

are fully booked with a group for the next few nights, so I've made arrangements for you to stay elsewhere.”

I have been emphatically warned by Ricki, a staff member at Women for Women headquarters. “Orchid is the

only

place to stay,” she told me. “Nowhere else is secure.”

only

place to stay,” she told me. “Nowhere else is secure.”

It was a major point of discussion, actually, when Kelly announced she wanted to do a homestay for a few days. When I ran the idea past a few veteran Congo travelers, they all said the same thing. No way. Not safe.

“What is Kelly doing in Congo, anyway?” they all asked.

In her own words, I told them, she wants to “cry with the women. To grieve with them.”

My policy-wonk friends scoffed, but hey, more power to her. There will be plenty of time to sing “Kumbaya” with the people. And I'm happy to be with a friend and split expenses

.

I do, however, have a tangible goal. Congo needs a movement. We only raised US$60,000 in the second year of Run for Congo Womenânowhere close to the million dollars I hope will spark a movement

.

But if we can put a human face on the horror, and document all facets of the conflict in a film, we would have ammunition for advocacy meetings. We could raise that million dollars through screenings and house parties, and generate a buzz that could ignite the grassroots movement for Congo. A good omen landed in my email in-box just before my departure: A producer from a major news network is interested in an American angle on the conflict. They might want my story and footage!

.

I do, however, have a tangible goal. Congo needs a movement. We only raised US$60,000 in the second year of Run for Congo Womenânowhere close to the million dollars I hope will spark a movement

.

But if we can put a human face on the horror, and document all facets of the conflict in a film, we would have ammunition for advocacy meetings. We could raise that million dollars through screenings and house parties, and generate a buzz that could ignite the grassroots movement for Congo. A good omen landed in my email in-box just before my departure: A producer from a major news network is interested in an American angle on the conflict. They might want my story and footage!

Goals aside, the security threats are real. Before I left, Ricki also impressed on me how quickly things can go wrong when she filled me in on her visit to Congo.

“We were there in April 2006,” she told me. “Zainab was shooting follow-up footage for

Oprah

, and I was supposed to show our program to a judge for the Conrad Hilton Award, a major humanitarian prize. The first day, Zainab went to the Bukavu ghetto to follow up and we set out to a rural area to meet women.

Oprah

, and I was supposed to show our program to a judge for the Conrad Hilton Award, a major humanitarian prize. The first day, Zainab went to the Bukavu ghetto to follow up and we set out to a rural area to meet women.

“We didn't make it.

“We got in the car with the driver and Christine, who has four different cell phones, one just for security updates. She got a call. We couldn't go down this street, a main road in Bukavu. Students were protesting. It was Easter break and the police shot someone. Protesters marched with his body over to the governor's house and left it on the front steps

.

.

“We immediately did a U-turn. Thirty seconds later, I saw two huge UN tanks in front of us, coming down the road, heading towards the protesters. One of the tanks passed, turned their gun at meâlike two feet from my head. But I was thinking, okay, they are experts, they aren't going to shoot me.

“The first tank passed and the second tank was coming our way. The only thing between us was a guy on a motorcycle. The tank swerved into our lane and we heard the motorcycle getting crushed. The rider started screaming.

“The tank stopped there. The guy's legs were pinned underneath, and the UN tank didn't roll off

.

One of the UN guys was just looking around, calm, surveying the scene for a good few minutes, not emotional at all. He was looking each way while the guy was screaming

.

A woman was right next to our car yelling at the UN to get off the guy! There were maybe fifty people around. Everyone was yelling. Finally, the tank rolled off the guy and just rolled on down the street, leaving him there. Congolese people picked him up and dragged him out of the street. Then everyone turned toward our car, and they saw me sitting in the front seat. They saw my big sunglasses. Christine told me they thought my sunglasses were a video camera of some kind, they thought I was filming. They started to crowd around the car, screaming. Our driver just pulled out and escaped up a dirt road. All the while, the Conrad Hilton judge was in the back seat.

.

One of the UN guys was just looking around, calm, surveying the scene for a good few minutes, not emotional at all. He was looking each way while the guy was screaming

.

A woman was right next to our car yelling at the UN to get off the guy! There were maybe fifty people around. Everyone was yelling. Finally, the tank rolled off the guy and just rolled on down the street, leaving him there. Congolese people picked him up and dragged him out of the street. Then everyone turned toward our car, and they saw me sitting in the front seat. They saw my big sunglasses. Christine told me they thought my sunglasses were a video camera of some kind, they thought I was filming. They started to crowd around the car, screaming. Our driver just pulled out and escaped up a dirt road. All the while, the Conrad Hilton judge was in the back seat.

“We decided to do interviews at the office instead of in the field

.

.

“At the office the next day, we heard that the security situation was getting worse. Zainab said I should go back to the hotel and pack our bags, and we could be on a plane in a few hours. âJust lie down in the back of the car on the ride back to Orchid,' she told me. So the Women for Women car

pulled up in the middle of the street and I was walking from the office gate to the car, when all of a sudden I heard âpow-pow-pow-pow.' About a hundred scared-shitless Congolese were running towards me. Christine yelled, âDon't run! Don't run!' But I ran straight back to the gate, and all these people were crowding around, trying to get back into the compound while the security guys were trying to close the gates.

pulled up in the middle of the street and I was walking from the office gate to the car, when all of a sudden I heard âpow-pow-pow-pow.' About a hundred scared-shitless Congolese were running towards me. Christine yelled, âDon't run! Don't run!' But I ran straight back to the gate, and all these people were crowding around, trying to get back into the compound while the security guys were trying to close the gates.

“I stuck my arm in through the crowd and they pulled me in. Zainab was just standing there asking, âWhat's going on?'

“I decided I wasn't going anywhere. So I started to film the rest of Zainab's interview, then we heard shots again, right outside the gate. I dropped the camera and ran around the compound in circles, because there was nowhere to go. Zainab just laughed and said, âIt's worse in Iraq.'

“I was like, âStop laughing. It's not funny.'

“She says, âI laugh in these situations.'

“We left that afternoon.”

Â

RICKI'S WARNINGS ARE flashing in my head like a stoplight, so the news about Orchid being overbooked does not land well. In the States, I am not known for my restraint when unhappy. Now I feel as if I have one foot on the brake and one the accelerator

.

Every minute of my countdown to Congo, every warning, presses down harder on both.

.

Every minute of my countdown to Congo, every warning, presses down harder on both.

But I've also been forewarned: People in Congo don't get mad. It would be viewed as a temper tantrumâit's something you don't do, like crying in a board meeting. As one Congo travel veteran warned emphatically, “If you lose it, just pack up; leave. You might as well never come back. You will have permanently lost the respect of the Congolese.”

So I smile at Christine and laugh. “Flexible is the name of the game in Congo,” I say. “It's no problem.”

We pull off to the side of the road and I get my first glance of the border crossing, just a simple bridge, shorter than a city block. I recognize it from Lisa Ling's report. I pull out my broadcast-quality HDV camera.

I position myself with the bridge in the background. Christine holds the camera for me, trying to be low-key. It's illegal to film borders. I try to control my face twitching and I dive right in with the commentary. “I'm standing on the border of Congo . . .”

As we approach the bridge, leaving Rwanda behind, I'm amazed that this old, rotting wooden bridge from Belgian Congo is all that separates the country from Rwanda

.

On the other side of the bridge, a man lifts the old metal gate and lets us through.

.

On the other side of the bridge, a man lifts the old metal gate and lets us through.

Whew. That was easy.

We drive up a hill about two city blocks before we hit the real border crossing, on the Congo side. Men in shabby tracksuits, sporting Kalashnikovs, lurk by the side of the road. I get out and enter a small cement-block room, where Congolese border officials size me up, stamp my paperwork, and usher me out again. Back in the SUV, three men approach and survey the car's contents, standing uncomfortably close to my window, glaring. One of them presses my hosts for God knows what. His eyes confirm the folkloreâthey tell me I'm in Congo, with their hard, glazed-over look that makes me wonder what he's seen, what he's done, and if there is a soul left inside.

Christine meets him with a laugh.

Is she teasing him?

I can't tell, but I'm taking mental notes.

Laugh. Laugh. When in danger, laugh. Everyone is your best friend.

Is she teasing him?

I can't tell, but I'm taking mental notes.

Laugh. Laugh. When in danger, laugh. Everyone is your best friend.

They want to search the car. My driver shoves cash toward the man and says something. Christine translates, “The driver told that guy to buy himself a Coke.”

As we pull away, I hum to myself that Coke ad from the eighties, the one they played during Saturday morning cartoons.

Â

I' d like to buy the world a Coke,

And furnish it with love . . .

Something, something, turtle doves . . .

It's the real thing.

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Real Thing

WELCOME TO BUKAVU,

a far cry from Rwanda. I stare out my Range Rover window, which is rolled all the way up tight, and comb the scene on Bukavu's main drag. The landscape is identical to what I saw in Rwanda. Hills jut along the lake, forming pockets and outcrops draped with greenery. Each hill, dotted with compounds, is a mirror image of the next one.

a far cry from Rwanda. I stare out my Range Rover window, which is rolled all the way up tight, and comb the scene on Bukavu's main drag. The landscape is identical to what I saw in Rwanda. Hills jut along the lake, forming pockets and outcrops draped with greenery. Each hill, dotted with compounds, is a mirror image of the next one.

In Bukavu, however, the signs are everywhere that all is not well. It feels raw and dusty. Corroded shopfronts and old lakeside villas stand like outlines in chalk, sketches of a dignified past, imprints of a grandeur that has been stripped and rotted under the chokehold of chaos. I can picture the villas filled with pleasure seekersâpeople on holiday alongside Mobutu in the lush gardens, savoring tropical fruit and tea with sugar and milk. Today, the old villas are either roofless, crumbling shells or they're shrouded by high cement walls capped with razor wire and jagged shards of glass, men in hand-me-down security uniforms stationed at their rusty gates.

Open-air jeeps marked “UN” crawl up and down the streets; they are mounted with giant machine guns and cramped with Pakistani army guys whose hands never wander far from the trigger. Traders line the streets with wooden

crates; they're selling phone cards, cassava flour, soaps, or clothes that look they were rescued from Goodwill bins. The washed-out roads are more like dry river-beds. I was warned I will need an SUV to drive anywhere outside of Bukavu, but by the look of things, I'll need an SUV to get anywhere inside Bukavu too. The air is different here. Rwanda breathes; purged of demons, cleansed with soft rains and the government's progressive agenda, it hums with prospects. Not so in Congo. The air here is thick with paranoia, like rancid garbage dumped by strangers and left to fester in the yard.

crates; they're selling phone cards, cassava flour, soaps, or clothes that look they were rescued from Goodwill bins. The washed-out roads are more like dry river-beds. I was warned I will need an SUV to drive anywhere outside of Bukavu, but by the look of things, I'll need an SUV to get anywhere inside Bukavu too. The air is different here. Rwanda breathes; purged of demons, cleansed with soft rains and the government's progressive agenda, it hums with prospects. Not so in Congo. The air here is thick with paranoia, like rancid garbage dumped by strangers and left to fester in the yard.

Women, like pack mules, carry loads of cassava flour, firewood, stone, and other commodities up steep hills. Sometimes their cargo is twice their size. With the impassible roads and gutted local economy, there are few vehicles left and all the livestock and bicycles have been looted. The transport of last resort is the backs of women. They transfer petty goods to keep the essentials of life and the local economy crawling forward. Those loads must weigh, what, 150 pounds? Hunched over, women lug the loads with straps slung around their foreheads, digging into their skin. They are sweating, steady, focused. It's a struggle journalist Ted Koppel once compared to the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was destined to keep rolling a boulder up a mountain, only to have it roll back down, again and again, for all eternity.

Surprisingly, the Congolese seem to be quite fashion-conscious. Their clothes are neat and pressed, with their hair in colorful braids or wigs; they wear traditional African wraps and dresses or sport American cast-offs: T-shirts, fashion jeans, and sporty tennis shoes. Many look worthy of a Diesel ad campaign. One local hipster seems perfectly packaged to open an indie rock concert as he saunters around in a tiger-print cowboy hat and a faux-fur-lined jacket, peering out from behind trendy sunglasses.

But all that primping can't hide the unmistakable mark of war in these people's eyes. I notice the eyes again when we arrive at the Women for Women compound, a two-story whitewashed building surrounded by round, open-air classrooms built of wood and straw. Morning classes disbanded some time ago, but three women linger in the courtyard garden of cosmos and marigolds.

Two of them inch towards me, curious. With the impenetrable language barrier between us and no one around to translate, we smile and attempt a few false starts at conversation that can't get beyond “Hello.”

Two of them inch towards me, curious. With the impenetrable language barrier between us and no one around to translate, we smile and attempt a few false starts at conversation that can't get beyond “Hello.”

“My name is Lisa,” I say, pointing to myself. “Lisa. Lisa. I am a sponsor.”

They say something back in Swahili, but it is completely lost on me. We smile with resignation. I watch an older lady standing at a cautious distance. She doesn't smile, barely looks at me. I see the glazed-over look, the same one I saw in the guy at the border. I move closer to her. We say nothing.

Other books

Kill Kill Faster Faster by Joel Rose

Murder Under the Tree by Bernhardt, Susan

Pearl in the Sand by Afshar, Tessa

ROOK AND RAVEN: The Celtic Kingdom Trilogy Book One by Delcourt, Julie Harvey

Plain Jayne by Brown, Brea

Education Of a Wandering Man (1990) by L'amour, Louis

Scorpius by John Gardner

Always Be True by Alexis Morgan

Tess Awakening by Andres Mann

Jordan St Claire: Dark and Dangerous by Carole Mortimer