A Thousand Sisters (4 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

“During World War II, a lot of people pretended not to know what was going on. Well, there's another holocaust going on. This time, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And if you are like most people, you probably had no idea.”

What?

In the report, journalist Lisa Ling describes a conflict born out of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. After the mass killings, the Hutu militias responsible were pushed west over the border into Congo, where they retreated into the forests and began to terrorize the local population. The militias that were formed to fight them soon began fighting each other. Eventually, half a dozen countries were involved in the conflict, which became known as Africa's First World War.

Oprah adds, “And the violence continues

today,

as we speak.”

Women

have suffered the worst of it; rape and sexual slavery are widespread, and once they've become victims, women are usually rejected by their husbands. “Four million people have died.

Four million people.

And no one is talking about it,” Lisa Ling reports. “I think it's the worst place on earth . . . and the most ignored.”

today,

as we speak.”

Women

have suffered the worst of it; rape and sexual slavery are widespread, and once they've become victims, women are usually rejected by their husbands. “Four million people have died.

Four million people.

And no one is talking about it,” Lisa Ling reports. “I think it's the worst place on earth . . . and the most ignored.”

Wait. Wait. Wait

.

Let's be clear. The militias responsible for the Rwandan genocide are still out there? Killing people?

.

Let's be clear. The militias responsible for the Rwandan genocide are still out there? Killing people?

Oprah says, “They are hoping somebody in the world will hear their screams for help

.

”

.

”

Could I be one of those people?

Zainab Salbi, founder of the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Women for Women International, appears on the show

.

The articulate, thirtysomething Iraqi American woman suggests sponsoring a Congolese woman for $27 a month. Oprah concludes, in an unusually pointed tone, “Now that you know, you can't pretend you didn't hear it.”

.

The articulate, thirtysomething Iraqi American woman suggests sponsoring a Congolese woman for $27 a month. Oprah concludes, in an unusually pointed tone, “Now that you know, you can't pretend you didn't hear it.”

I' ll do that. I' ll sponsor a woman.

The show ends. Ted shouts from the next room, “Would you like some tea?”

The phone rings. I chat with my mom for a couple of minutes

.

I check email then initiate the daily discussion, calling to Ted in the next room. “Where should we have dinner?”

.

I check email then initiate the daily discussion, calling to Ted in the next room. “Where should we have dinner?”

Walking down the hall, heading for my tea, I remember the show. I know how this will go. My mind will drift to cash-flow charts scrawled on yellow legal pads. I'll log onto modeling agency sites to see what new face might spark a shoot idea. I'll move on. Weeks, months, maybe years will stack up, and I'll think back to those faces, those numb eyes I saw on

Oprah,

and wonder,

What if I had tried to help?

Oprah,

and wonder,

What if I had tried to help?

I have to do it now, before it becomes one more thing I meant to do.

I stop, turn around, go back to the computer, and sign up to sponsor two women. I am one of six thousand viewers to sign up as a sponsor because of Oprah's show.

THE WOMEN'S FACES don't retreat, though. And I continue to feel like something is missing in my life. I'm hungry for something all my own, beyond Ted and Lisa, Inc. I want to do something, but I can't think of what. There is this faint sense, somewhere in the background, of a person I haven't seen in a long time: the person I always imagined I would become.

I stop, turn around, go back to the computer, and sign up to sponsor two women. I am one of six thousand viewers to sign up as a sponsor because of Oprah's show.

THE WOMEN'S FACES don't retreat, though. And I continue to feel like something is missing in my life. I'm hungry for something all my own, beyond Ted and Lisa, Inc. I want to do something, but I can't think of what. There is this faint sense, somewhere in the background, of a person I haven't seen in a long time: the person I always imagined I would become.

I remember the day when I was eleven and my older sister, Marie, and I met my mom for lunch downtown, where she worked as a legal secretary.

Afterward, Marie and I walked to the bus stop. I took the last available seat on the bench, next to an African American lady. Marie stood beside me as we waited. A few minutes later, a disheveled homeless man, probably drunk, approached. He asked, “Can you spare any change?”

One of us responded. “Don't have any, sorry.”

He turned to the lady next to me, who gave him the same polite answer. As he turned to walk away, he sputtered none too quietly, “Fââing nââ.”

It was one of those moments when time slows, like during a traffic accident. My heart beat heavily. An impulse overtook me.

I can't just let that go.

I jumped to my feet and blurted out, “You are a

racist!”

I can't just let that go.

I jumped to my feet and blurted out, “You are a

racist!”

My skin burned. Everyone milling around the bus stop stood still. My sister was shocked. The lady was shocked. I was shocked. Yet I continued. “I don't want to hear your garbage!” I said. “You have no right to judge people by the color of their skin. You need to watch your mouth!”

The man looked at me for a moment, then turned around and shuffled away, murmuring, “Damned kids . . .”

Then there was that time after a gym-class volleyball game, during my freshman year of high school, when I noticed a group of boys swarming around the net. It was another problem with Trevor Samson, the school geek. This time he was in a verbal sparring match with a popular kid, one of those who commuted to school from their prestigious, sprawling West Hills homes in spanking new Jeep Cherokees. I didn't care that Trevor and I had a lot in commonâwe'd been in middle school together, and we came from the same

part of town. We weren't friends. I didn't like him. He was a nerd's nerd: obnoxious. Vulnerable. Pathetic.

part of town. We weren't friends. I didn't like him. He was a nerd's nerd: obnoxious. Vulnerable. Pathetic.

The confrontation heated up quickly as I edged in closer to see what was going on. No teachers were in sight. More than thirty boys, mostly of the West Hills breed, had gathered around and were egging on the aggressor. They wanted to see a fight. As people started pushing and violent threats were hurled, Trevor was saying all the wrong thingsâthe kind of defensive garbage that only fuels the confrontation. Boys shouted from the crowd, “Kick his ass!”

Without considering the social risk, I pushed my way past the pack and stepped between Trevor and Mr. Popular. I stuck my finger in Chip-or-Chador-Seth's face and declared, “Stop!”

A kid with the chiseled features and glowing tan that seem to come with a moneyed background shouted from the herd, “Shut up, you fâing hippie bitch!”

I stood my ground, squarely in front of Trevor, shielding him with the hard fact there is no social status to be gained from hitting a girl. The crowd disbanded.

Later that year, I saw an ambulance in front of the school. Down the main corridor, covered in bandages, came Trevor; he was being wheeled out by paramedics. Someone had cornered him in the locker room and beaten his head against the cement floor until he collapsed, bloody. The teacher who found him called 911.

A lot of us, when we were kids, couldn't stand to see a starving stray cat.

It's not right,

we'd think.

Something has to be done

. Then, somewhere between ages fifteen and twenty-five, the feeling fades. We shut up. We get “real.” We learn to mind our own business.

It's not right,

we'd think.

Something has to be done

. Then, somewhere between ages fifteen and twenty-five, the feeling fades. We shut up. We get “real.” We learn to mind our own business.

I've been no exception.

Â

STILL, ABOUT A WEEK LATER on my last-day-of-my-twenties party, I abandon social graces and herd the conversation back to Congo at every turn. “No, you

don't understand. Four million people have died. Don't you think we should do something? Let's have a fundraising party or bake sale or walk. . . .”

don't understand. Four million people have died. Don't you think we should do something? Let's have a fundraising party or bake sale or walk. . . .”

I am met with awkward silences, blank stares, and polite changes of subject.

Despite attempts to map new terrain for myself, I wake up on the morning of my thirtieth birthday without a clue about where I am headed. Ted says he has a surprise for me. Whatever it is, I welcome the change.

On my last birthday, we were in San Diego prepping a photo shoot. We spent hours in sprawling malls, driving from one chain store to another. We roamed the aisles at Target, Ross, and the Saks Fifth Avenue outlet, hunting for size 2 summer dresses and swimsuits. By the time evening came around, we abandoned plans to eat at the nicer strip mall restaurant, opting for rice and beans at the Baja Fresh across the parking lot to avoid the long lines outside the marginally fancier place. Back at the hotel, Ted presented me with my birthday treatâa card picked up while we were prop shopping. I stayed up late, wrapping empty boxes in flower-print and striped gift paper and tying them with inviting bows for the next day's shoot, a fake child's birthday celebration.

So wherever I am headed to inaugurate my thirties, it's already something better. When we get in the car, I have no idea: The beach? The mountains? The desert? The train? A drive? The airport? I'm not used to this lack of control, “Can you at least tell me when I'll know?”

“Soon,” Ted teases.

When we pull up at the airport, I am just as lost, even after we check in for our flight to San Francisco

.

.

As we sit in the airport terminal, I spot a newsstand with the February issue of

O, The Oprah Magazine,

which has an article on women in Congo. Minutes later, in the crowded waiting area, I read the article, then its online expanded version, “Postcards from the Edge.” One woman describes a militia dragging her away to the forest to rape or kill her. She pleads for her life. One of the militia responds, “Even if I kill you, what would it matter? You are not human. You are like an animal. Even if I killed you, you would not be missed.”

O, The Oprah Magazine,

which has an article on women in Congo. Minutes later, in the crowded waiting area, I read the article, then its online expanded version, “Postcards from the Edge.” One woman describes a militia dragging her away to the forest to rape or kill her. She pleads for her life. One of the militia responds, “Even if I kill you, what would it matter? You are not human. You are like an animal. Even if I killed you, you would not be missed.”

I decide to run.

CHAPTER FOUR

Lone Run

I AM NOT A

feel-the-burn kind of girl. I am a casual runner. Make that very casual.

feel-the-burn kind of girl. I am a casual runner. Make that very casual.

Years ago, my then roommate and I decided to train for our first marathon. We trained consistently for about a month, then scheduled our first fourteen-mile training run. We procrastinated until late afternoon, forgot our water, and set out in ninety-five-degree heat on an endlessly flat, sun-exposed cement path. (I still call it “The Corridor of Hell.”) Our chatter about frozen dessert could only keep us distracted for so long, and around mile ten, it trailed off into the sound of panting and footsteps. My running buddy asked, “How are you doing over there?”

“Exhausted,” I admitted.

“Want to stop?” he asked.

“Got your cell phone?”

“No,” he said, then he pointed to a convenience store. “But I bet they have a pay phone there.”

We called a cab to drive us back to the car. I collapsed in the back of the taxi, delighted to declare that giving up was one of the nicest things I'd ever done for myself. That marked the end of my marathon ambitions.

Now, back from our San Francisco trip and over my midwinter bug, I find a five-mile run long, but doable. Though I've tried to enroll friends to join me in creating a run or walk for Congo's women, not one of them has agreed. They don't know anything about the conflict and aren't interested in learning. So I'm doing this alone. Because everyone and their cousin's boyfriend do 5Ks and marathons to raise funds for every cause imaginable, I need to take it a step further. I realize I need an effort that can't be faked: something extreme. Something that will get my friends and family to see how seriously, how personally, I take the situation in Congo.

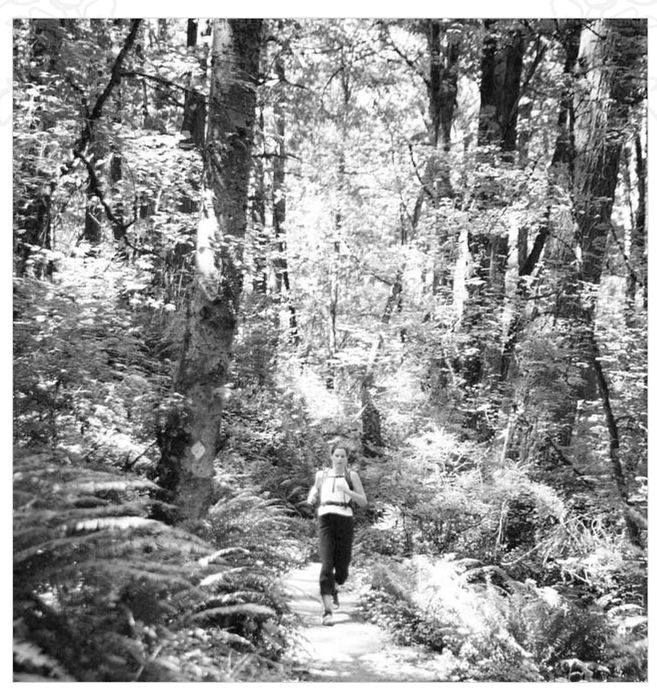

So I decide to run 30.16 miles, the entire length of Wildwood Trail, a muddy, rugged forest trail which zigzags up and down Portland's West Hills. My goal is to raise thirty-one sponsorships for Congolese women through Women for Women International, one sponsorship for every mile I run.

I'm not sure I can do it. That's why at first I keep it a secret.

Everyday I hit the trail alone. Each week I go on the longest run of my life. I hire an ultrarunning coach and follow her training schedule to the letter. Ted drops me at the trailhead in the morning. While he works for hours, grocery shops, and does laundry, I pound miles of trail, getting smacked in the face with branches and spider webs. If I'm lucky, I brush them off my face or hair. Less lucky for me and the spider, I sometimes get a surprise high-protein snack.

Â

I REALLY NEED TO PEE. Never mind public toilets; I am ten miles from the nearest porta-potty. Without any other option, I climb off the trail to the most secluded, dense underbrush I can find and I squat. When I continue on my way, I run like a snail. I crawl, shuffle, wince, and spend miles trying to forget what I'm doing. I try all kinds of mental tricks, from counting my steps to reciting the Vedic prayer I sang to my dad when he died and composing letters to my future Congolese sisters. Anything to distract myself from the searing pain that shoots from my sciatic nerve. Anything to get through the remote stretches of the park where I don't see another jogger for hours. When I reach

the more populated section, everyone is faster than I am. As college girls in bushy-bushy ponytails bounce straight past me, I reassure myself: They are probably on mile two; I'm on mile eighteen.

the more populated section, everyone is faster than I am. As college girls in bushy-bushy ponytails bounce straight past me, I reassure myself: They are probably on mile two; I'm on mile eighteen.

Another jogger rounds a corner and says, “Nice job!” as he passes. I mumble on an exhale, “Thanks,” and then get misty-eyed! No one ever warns you that on these long stretches, with the body's resources beyond tapped, you get wiggy.

On the final stretch, I feel like I'm running while I have the flu. I was overly optimistic about my pace again. Ted has been sitting dutifully in the car, waiting almost an hour for me to round the last curve of the trail and emerge, sweaty and exhausted. When I see him waiting with a cold bottle of water and a sandwich, I think,

That's love

. My gait disintegrates to a crumpled, stiff shuffle back to the car.

That's love

. My gait disintegrates to a crumpled, stiff shuffle back to the car.

Other books

Presumed Dead by Shirley Wells

Faith by Michelle Larks

Any Duchess Will Do by Tessa Dare

The Stardance Trilogy by Spider & Jeanne Robinson

The Book of Transformations by Newton, Mark Charan

The Persian Pickle Club by Dallas, Sandra

Sea of Dreams (The American Heroes Series Book 2) by Kathryn Le Veque

Holly Black by Geektastic (v5)

Memories of the Storm by Marcia Willett

Grim Crush (Grimly Ever After) by S.L. Bynum