A Thousand Sisters (2 page)

Read A Thousand Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Shannon

I would like to offer a special thanks to Oprah Winfrey, whose vision

and passion led her to cover the story of the women in Congo before anybody else brought awareness to the issue. If Oprah had not given me the opportunity to share the story of Congolese women, I would not have had the privilege of meeting Lisa and the thousands of other women who decided to act.

and passion led her to cover the story of the women in Congo before anybody else brought awareness to the issue. If Oprah had not given me the opportunity to share the story of Congolese women, I would not have had the privilege of meeting Lisa and the thousands of other women who decided to act.

I will close with this final thought: a Bosnian journalist once told me that war shows you the worst side of humanity and in that same moment it shows the most beautiful side of humanity. Lisa's story is a testament to the beauty of humanity that exists in the darkest and most depraved times of war. It is a beauty that has sparked the united action of women who gather in support of their Congolese sisters across the globe, who gather to speak out, and who gather to create change.

Rumi, a 13

th

century Sufi poet, wrote :

th

century Sufi poet, wrote :

Â

Out beyond the world of right doing and wrong doing

There is a field.

I will meet you there.

When the soul meets in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase

each other

no longer makes any sense.

There is a field.

I will meet you there.

When the soul meets in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase

each other

no longer makes any sense.

I hope Rumi forgives me if I suggest that in between the worlds of war and peace, there is a field, and women are meeting in that field. Lisa is there; Honarata is there; Fatima is there; Violette is there; Barbara is there; so many other sisters are there. If you are not there already, come join us, for the “world is too full to talk about. Ideas, language, even the phrase

each other

no longer makes any sense.” We are just sisters gathering in a field, and we shall runârun and danceâdance until the end.

each other

no longer makes any sense.” We are just sisters gathering in a field, and we shall runârun and danceâdance until the end.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

THIS IS A TRUE STORY.

In a place as extreme as Congo, there is no need to make anything up. Everything in this book happened; the vast majority of it happened on videotape. Most of the dialogue has been transcribed directly from video, as it was translated to me in the moment. Some interviews are compressed, having taken place over multiple meetings. Some portions are not presented in the exact order of actual events. There are no composite characters. Congo, nonetheless, is an active war zone and I have a duty to protect those I met and interviewed. Most names have been changed, primarily for safety reasons, and in some special cases (as clearly noted in the text) details of context were omitted due to serious safety concerns.

In a place as extreme as Congo, there is no need to make anything up. Everything in this book happened; the vast majority of it happened on videotape. Most of the dialogue has been transcribed directly from video, as it was translated to me in the moment. Some interviews are compressed, having taken place over multiple meetings. Some portions are not presented in the exact order of actual events. There are no composite characters. Congo, nonetheless, is an active war zone and I have a duty to protect those I met and interviewed. Most names have been changed, primarily for safety reasons, and in some special cases (as clearly noted in the text) details of context were omitted due to serious safety concerns.

INTRODUCTION

Congo in a Nutshell

AT THE END

of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, more than two million Hutu refugees fled over the border into Zaire. Among them, approximately 100,000 Hutu

genocidaires,

known as the Interahamwe, found safe harbor, melting into refugee camps facilitated by the United Nations.

of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, more than two million Hutu refugees fled over the border into Zaire. Among them, approximately 100,000 Hutu

genocidaires,

known as the Interahamwe, found safe harbor, melting into refugee camps facilitated by the United Nations.

In the absence of an international effort to identify Interahamwe, in 1996 Rwanda and Uganda sponsored rebel leader Laurent Kabila to invade Zaire. The Hutu refugee camps were destroyed. The remaining Interahamwe retreated to Congo's forests, where they re-branded themselves as the Democratic Liberation Forces of Rwanda (the FDLR).

Backed by Rwandan troops, Kabila ousted Zaire's long-time kleptocratic dictator Mobutu. Kabila was installed as the new President of the country and renamed it The Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The alliance between Rwanda and Kabila was short-lived. In 1998, again citing security threats posed by the Interahamwe (FDLR), Rwanda and Uganda invaded once again, now backing the militia Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), which took control of North and South Kivu provinces. Ragtag splinter groups and homegrown militias jumped into the fight, including the Mai Mai, a local defense force known for its use of witchcraft. Kabila formed his own alliances with neighboring countries like Zimbabwe, Angola, and

Namibia, dragging half a dozen countries into the conflict that grew to be termed Africa's World War.

Namibia, dragging half a dozen countries into the conflict that grew to be termed Africa's World War.

In January 2001, Kabila was assassinated. His son, Joseph Kabila, took over as President of DR Congo. The conflict technically ended in 2003 and many countries or their proxy militias returned home. In the summer of 2006, with heavy international support, Congo held its first elections since independence, and Joseph Kabila became the first democratically elected President since 1960. Despite this, chaos continues to reign in eastern Congo.

Congo hosts the largest United Nations peacekeeping force in the world, with 20,000 troops and a robust mandate to protect civilians. But given the enormity of the country and its chaos, the UN force, also called MONUC, is “pathetically spare,” while the Congolese army, a force of 125,000 troops, is comprised primarily of former militias integrated into this notoriously corrupt, ill-disciplined army.

The FDLR remain, still known by the locals as Interahamwe, “Those Who Kill Together.” Though they have shrunk to an estimated 6,000 to 8,000 combatants, they control 60 percent of South Kivu.

National Congress for the Defense of People (a.k.a., CNDP), a Congolese-Tusti defense force led by General Laurent Nkunda (widely reported to be backed by Rwanda), has caused major unrest and massive displacement in North Kivu through 2008. Nkunda was arrested in 2009.

The United Nations has accused all nations involved in the conflict of using the war as a cover for looting Congo's vast mineral wealth. Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi, as well as Congolese government officials, have made hundreds of millions of dollars off of the Congo plunder.

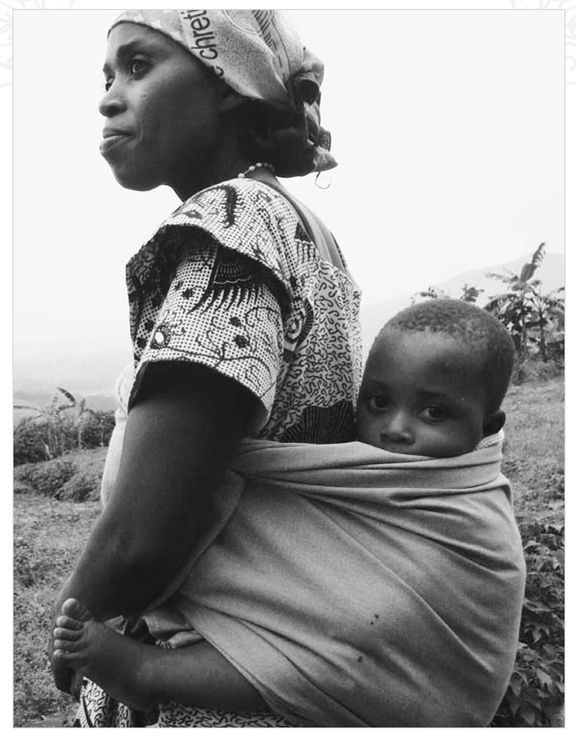

The result? As of January 2008, more than 5.4 million people had died due to the conflict, making it the deadliest war since World War II. Forty-five thousand continue to die every month. Sexual violence is rampant. Congo has been widely termed “the worst place on earth to be a woman.”

Journalist Lisa Ling has termed Eastern Congo, “The worst place on earth. And the most ignored.”

CHAPTER ONE

Congo Rushes

THE CALLS COME

during the remote, panic-inducing hours of morning. I scramble for my cell phone; a number beginning 011-243-99 appears on my caller ID. Congo calling. Sometimes it's the United Nations, a Sergeant Something-I-Can't-Make-Out, with a heavy South Asian lilt, who requests my immediate reply but is never again reachable. The president of a militia calls for a job reference after being fired for “political affiliations incompatible with humanitarian work.” Or it's the distant voice of my Congolese driver, Serge, who says, “Some fââing job.” He is using his precious phone minutes to prank call me. We both giggle until he hangs up.

during the remote, panic-inducing hours of morning. I scramble for my cell phone; a number beginning 011-243-99 appears on my caller ID. Congo calling. Sometimes it's the United Nations, a Sergeant Something-I-Can't-Make-Out, with a heavy South Asian lilt, who requests my immediate reply but is never again reachable. The president of a militia calls for a job reference after being fired for “political affiliations incompatible with humanitarian work.” Or it's the distant voice of my Congolese driver, Serge, who says, “Some fââing job.” He is using his precious phone minutes to prank call me. We both giggle until he hangs up.

The Democratic Republic of the Congoâotherwise known as the worst place on earth. Home to Africa's First World War, the deadliest war on the planet since World War II. I've spent months trying to shake that place, but it keeps knocking at my door, like a bill collector or an old lover anxious to wrap up unfinished business.

This morning is different, though.

“Do you remember there?”

Yes, Eric. I remember there.

It's news from the village of Kaniola. One Sunday, many months ago, I walked through its far-flung settlements, which are scattered along the ridgeline, butted up against vast stretches of forest. Since the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the forests, thirty miles inland from the Rwandan border, have been ruled by Hutu militias known as Interahamwe, a Rwandan word meaning “those who kill together.” The group is also known as the

Forces Democratiques de Liberation du Rwanda,

or FDLR

.

Forces Democratiques de Liberation du Rwanda,

or FDLR

.

I thought about Kaniola just the other day while strolling past the Old Portland houses and walnut trees that line my street, sipping my takeout tea. I'm not religious, so Biblical passages almost never cross my mind, but that psalm flashed in my head:

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death

. . . I realized that if there is anywhere on earth that qualifies as the valley of the shadow of death, it's Kaniola. In the five and a half weeks I spent in Congo, the most horrific stories I heard came from that valley. I walked through it and I felt no fear.

I've done that, literally.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death

. . . I realized that if there is anywhere on earth that qualifies as the valley of the shadow of death, it's Kaniola. In the five and a half weeks I spent in Congo, the most horrific stories I heard came from that valley. I walked through it and I felt no fear.

I've done that, literally.

I chuckled to myself.

This morning, sitting in front of my laptop with another cup of tea, staring at my email in-box, it is not amusing in the least.

My friend Eric, a Congolese conservationist with whom I maintain regular contact, writes, “I am forwarding you an article about seventeen persons who were killed by knives in Kaniola. Do you remember there?”

Of course I remember.

The international news report outlines the attack. “It was a reprisal. They targeted houses. They silently entered the house. They started by strangling some victims before stabbing them to stop them raising the alarm. . . . The assailants left a letter saying they would return in force.”

Twenty injured. Eighteen kidnapped. Seventeen killed.

On my second read of the article, I stop cold at a line I initially missed: “The victims included the father of a girl kidnapped by the FDLR and recently freed by the army.”

From the hundreds of people I interviewed in Congo's war-ravaged

South Kivu province, I heard plenty of stories of abductions and countless reports of the army

running away

from the Interahamwe. But I heard only one account of the army protecting civilians, a shocking story because these kinds of heroics are so rare. In Kaniola, I met three girls who'd been abducted by the Interahamwe and rescued by the Congolese Army.

running away

from the Interahamwe. But I heard only one account of the army protecting civilians, a shocking story because these kinds of heroics are so rare. In Kaniola, I met three girls who'd been abducted by the Interahamwe and rescued by the Congolese Army.

Is this article about that same family?

It must be.

It must be.

It will be days before I hear from one of the United Nations majors who escorted me that day, who confirms my guess. “If you remember the last walk, it was that same area.”

I went to Kaniola on a tip, a shred of paper, on a day I had nothing better to do. I spent less than a day thereâjust a Sunday morningâwalking through the village, hoping to talk with the rescued girls. We visited the girls' home and spoke for more than an hour with the cool-tempered teenagers, their brother, and their desperate father. Afterward, their dad turned to us and asked pointedly, “Now that we've talked with you, what are you going to

do

?”

do

?”

I drag out the plastic storage bin packed with videotapes from my trip, long since left in a corner of an empty room, its contents unviewed. I'm up late, combing the unfiltered, raw footage, which are called “rushes” in the film industry. Finally I find the Kaniola tapes.

It's peaceful enough there. Certainly, there is no gore. (I never once saw a dead person in Congo.) Still, I notice my hands shaking as I watch. I have to stop, pace the hall, and return to inch through the footage, frame by frame, until I land on the clearest image of each person I so much as scanned with the camera that day. I capture them in still frames. I export them, save them, print them out in pixilated eight-by-tens, and file them in a white plastic three-ring binder.

I missed so much when I was there. I had heard that when you cross the border into Congo, the look in people's eyes changes. I noticed it the first day, then never again. Now, as I scan the video footage, it seems so obvious. I study their eyes. Countless people have referred to that look as one of numbness or shell shock. Journalist Lisa Ling once called it “a look of utter death.”

As days fly by and I continue to dig deep into the footage, I stumble across a shot of myself on my second day in Africa, standing on the Rwandan side of the border with a rickety wooden bridge in front of me. I'm about to cross over. I'm already disheveled from the thirty-five-minute flight from Kigali, Rwanda.

That's odd.

In the footage, I am blinking rapidly. My eyelids are fluttering. I didn't feel afraid at the time, but as I watch myself, I'm clearly scared. Why did I invite that place in? Why did I pursue it, track it down?

In the footage, I am blinking rapidly. My eyelids are fluttering. I didn't feel afraid at the time, but as I watch myself, I'm clearly scared. Why did I invite that place in? Why did I pursue it, track it down?

It wasn't because I wanted a feel-good pet project. I needed a solution.

Other books

Gone With the Wolf by Kristin Miller

The Twisted Knot by J.M. Peace

Diamond Willow by Helen Frost

El viaje de los siete demonios by Manuel Mújica Láinez

Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World by Williams, Mark, Penman, Danny

Arms of Serenity (Rock Services) by Lynn, Donina

The Other Anzacs by Peter Rees

Merrick by Bruen, Ken

The Meaning of Liff by Douglas Adams, John Lloyd

Deep Throat Diva by Cairo