A History of the World in Twelve Shipwrecks (39 page)

Read A History of the World in Twelve Shipwrecks Online

Authors: David Gibbins

Some of the lessons of convoy SL 64 were learnt, with orders from the Admiralty among the convoy records showing that care was to be taken in Freetown to ensure that ships were adequately fuelled and that all vessels not able to sustain 9 knots were put in the slow convoys. A respite from the air attacks that had caused many losses in the Western Approaches came in March 1941 when the FW-200 Condors were withdrawn in order to preserve their numbers, and a breakthrough came in early May when British warships captured a U-boat with an Enigma machine, allowing the German naval code to be cracked and leading to more successful decrypting â work carried out by Alan Turing and the codebreakers at Bletchley Park. These gains were offset by more proficient German âwolf-pack' tactics, where instead of hunting singly, the U-boats operated in co-ordinated groups, inflicting devastating losses on convoys. It was only when the Allies retaliated in kind, hunting U-boats with escort groups of specialised small ships â corvettes and frigates â and using sonar and depth-charging, that the war at sea swung in the Allies' favour. That did not take place

until 1943, and even so the U-boat danger was still severe â long-range U-boats by then operating in the Indian Ocean sank ships on routes that had previously been safe from German attack, including the route that the

Gairsoppa

had taken on her final voyage from Calcutta to South Africa in December 1940.

At no time in the war was the Atlantic safe for shipping, with the last British merchant ship being torpedoed in April 1945, five years and seven months after the first in September 1939. Of the twenty-seven ships in convoy SL 64, eighteen had been sunk by 1944, with the loss of 453 merchant seamen. The

Gairsoppa

was one of 51 ships under British India management lost during the war, out of a fleet of 123 vessels; the Clan Line lost 37 of 55 ships. By the end of the war, some 3,500 British-flagged merchant ships had been sunk, along with more than 930 Greek, 730 American, 690 Norwegian and 260 Dutch ships, as well as many Royal Navy and Allied warships that had been escorting them. On the other side of the balance, 785 U-boats had been sunk, many with all hands. These figures underline the enormity of the war at sea, which along with the losses of the First World War left a legacy of conflict from the twentieth century on the floor of the world's oceans far greater than that of any other period in history.

Richard Ayres spent nine months recuperating and then went to sea again. A letter he wrote in 1990, two years before his death, gives further details of the men who had been with him on the lifeboat to the end. There had been three Europeans â eighteen-year-old radio officer Robert Frederick Hampshire, twenty-year-old seaman gunner Norman Haskell Thomas and seventeen-year-old cadet John Martin Woodliffe â as well as two Indian seamen. Woodliffe's body was never recovered, but the other four lie buried in the churchyard of St Wynwallow at Landewednack a mile away from Caerthillian Cove, three of them under Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones set up in 1947 and one, Norman Thomas, under a cross provided by his family, with the epithet âhe died courageously'. Ayres wrote that he was interviewed in hospital nearby to help establish the identity of the bodies of the two Indian men, âbut as I was incapable of walking this was not possible, and they were buried after I had given my descriptions. The Asians, who were Mohammedans, were buried at my request in accordance with their religious rites ⦠facing Mecca.'

These men are among the sixty-three Indians in the crew whose names are known from the Lascar Agreements. All of them are listed in memorial books in Chittagong and Bombay for the 6,045 Indian merchant seamen who died during the war, and they are also among the 37,641 names of merchant seamen in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission register. Leong Kong, the Chinese carpenter on the

Gairsoppa

, is among 1,491 names on the Hong Kong Memorial to Chinese merchant seamen who died during the war; Royal Marine William George Price is named on the Chatham Naval Memorial, one of 3,935 gunners from the Navy, Marines and Army on merchant ships who died at sea; and the eleven British officers and ratings lost in the

Gairsoppa

or the aftermath with no known grave are among 24,543 names on the Merchant Navy Memorial to the missing at Tower Hill in London. More than 60,000 merchant seamen of all nationalities died during the war, with many of the survivors living lives permanently damaged and shortened by their experiences, as the

Official History

of the Merchant Navy put it. A senior Ministry of War Transport official who analysed the casualty rate concluded âIt needs little imagination to see behind the mere statistics the magnitude of the risks run and the courage that enabled the men of the Merchant Service to carry out their work. Without that, all would have been lost.'

The second millennium

BC

Bronze Age boat under excavation in Dover, England.

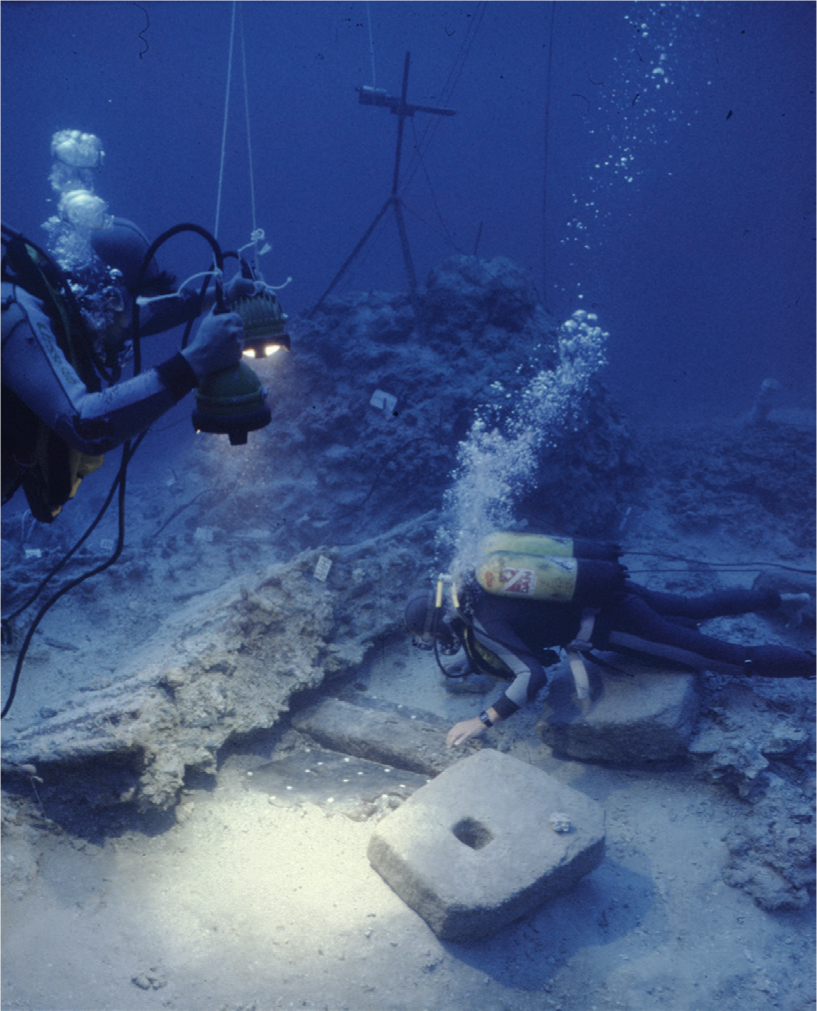

Excavation at 44â51 metres depth at the fourteenth-century

BC

Uluburun wreck off Turkey, showing stone anchors, hull timbers and stacked copper âoxhide' ingots.

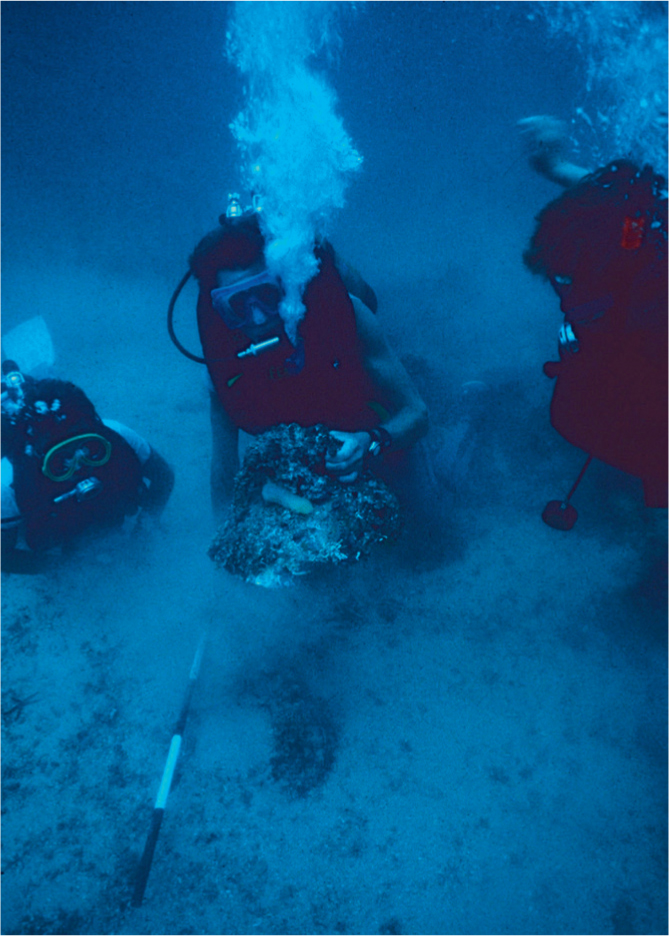

Excavation at the Uluburun wreck showing Canaanite jars on the left, a âpilgrim flask' and a kylix in the diver's hands, and a gold chalice in the centre.

The amphora mound at a depth of 38â43 metres at the fifth-century

BC

TektaÅ wreck off Turkey.

David Gibbins with an amphora from the Plemmirio Roman wreck off Sicily, Italy.

David Gibbins in Sicily with artefacts recovered from the Plemmirio Roman wreck, including amphoras, glass, kitchen pottery and oil lamps.

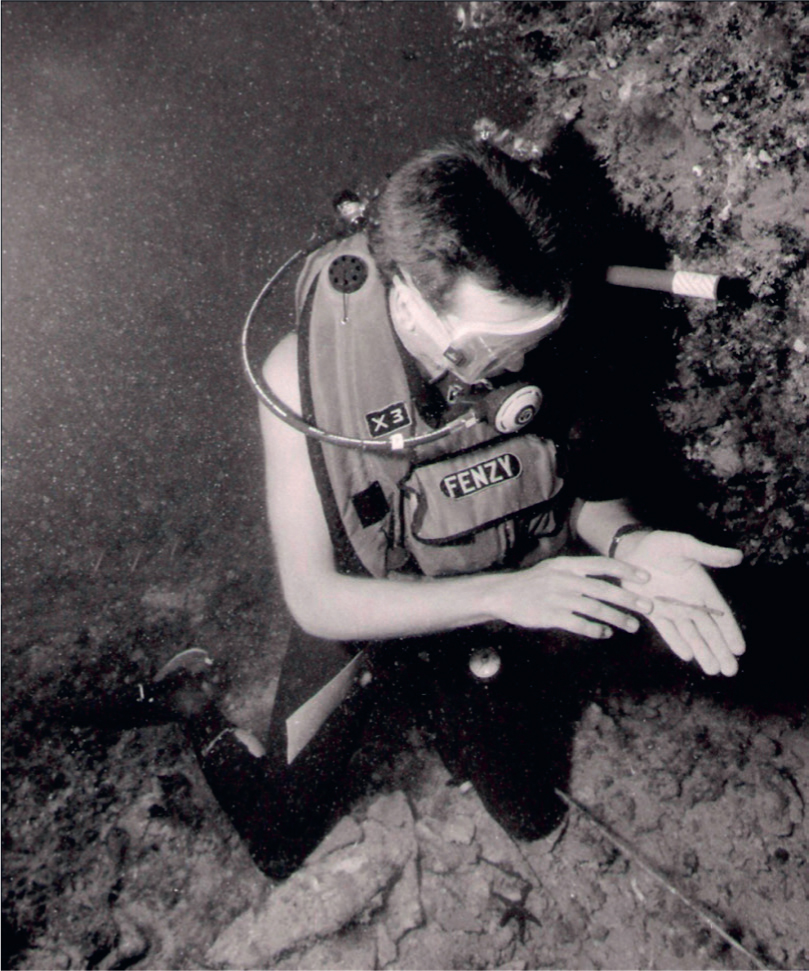

David Gibbins at 45 metres depth with an amphora top at the Plemmirio wreck.

David Gibbins at 27 metres depth on the Plemmirio wreck with a bronze scalpel.

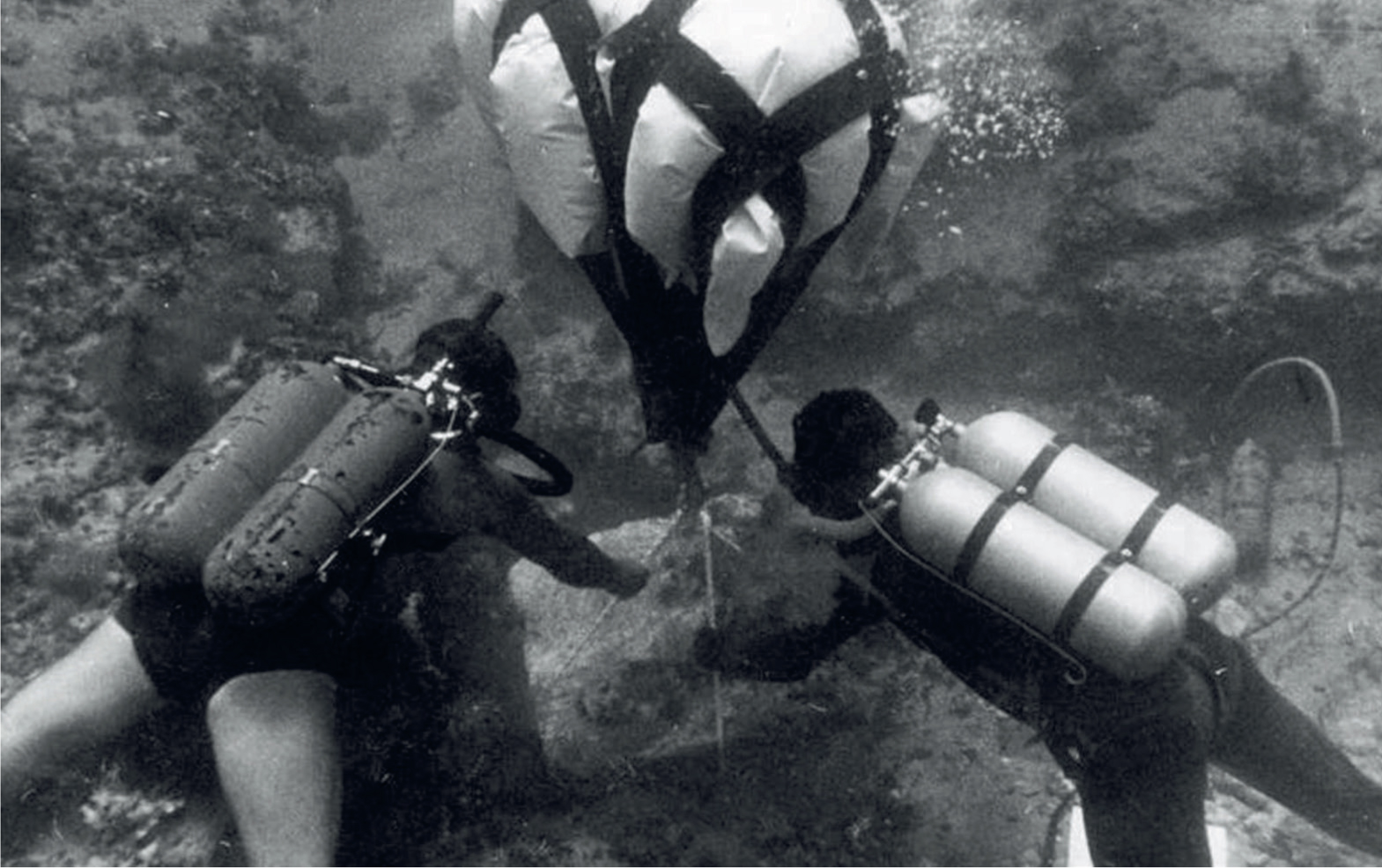

Divers in the 1960s using an air-filled lifting bag to raise a marble fragment from the sixth-century

AD

Church Wreck at Marzamemi, Sicily.