A History of the World in 100 Objects (8 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Bird-shaped Pestle

6000–2000

BC

Next time you are at the salad bar in a restaurant, look closely at the choice of vegetables on offer. It probably includes potato salad, rice, sweetcorn and kidney beans, all of which come originally from widely different parts of the world; nothing unusual about that nowadays, but none of them would exist in the nutritious form they do today if the plants they come from hadn’t over generations been chosen, cherished and profoundly modified by our ancestors. The history of our most modern cereals and vegetables begins about 10,000 years ago.

Previously, I have looked at how our ancestors moved around the world; now I’m going to be focusing on what happened when they settled down. It was a time of newly domesticated animals, powerful gods, dangerous weather, good sex and even better food.

Around 11,000 years ago the world underwent a period of swift climate change, leading to the end of the most recent Ice Age. Temperatures increased and sea levels rose rapidly by about a hundred metres (more than 300 feet), as ice turned to water and snow gave way to grass. The consequences were slow but profound changes in the way that humans lived.

Ten thousand years ago, the sound of daily life began to change across the world, as new rhythms of grinding and pounding heralded the preparation of new foods that were going to alter our diets and our landscapes. For a long time, our ancestors had used fire to roast meat; but now they were cooking, in a way that is more familiar to us today.

There’s an enormous range of objects in the British Museum that I could have chosen to illustrate this particular moment in human history, when people started putting down roots and cultivating plants that would feed them all year round. The beginning of this sort of farming seems to have happened in many different places at more or less the same time. Archaeologists recently discovered that one of those places was Papua New Guinea, the huge island just to the north of Australia, where this bird-shaped stone pestle comes from. We think it’s about 8,000 years old, and a pestle then would have been used exactly as it is now – to grind food in a mortar and break it down, so that it can be made edible. It’s a big pestle, about 35 centimetres tall (just over a foot). The grinding part, at the bottom, is a stone bulb, about the size of a cricket ball; it’s visibly worn and you can see that it’s been much used. Above the bulb, the shaft is very easy to grasp, but the upper part of this handle has been carved in a way that’s got nothing at all to do with making food – it looks like a slender, elongated bird with wings outstretched and a long neck dipping forward; indeed it looks a bit like Concorde.

It is a commonplace in every culture that preparing and sharing food unites us, either as a family or as a community. All societies mark key events with feasting, and a great deal of family memory and emotion is bound up in the pots and pans, the dishes and the wooden spoons of childhood. These sorts of associations must have been formed at the very beginning of cooking and its accompanying implements – so around 10,000 years ago, roughly the period of our pestle.

Our stone pestle is just one of many to have been found in Papua New Guinea, along with numerous mortars, showing that there were large numbers of farmers growing crops in the tropical forests and grasslands around this time. This relatively recent discovery has upset the conventional view that farming began in the Middle East, in the area from Syria to Iraq, often called the Fertile Crescent, and that from there it spread across the world. We now know that this was not the way it happened. Rather this particular chapter of the history of humanity occurred simultaneously in many different places. Wherever people were farming they began to concentrate on a small number of plants, selectively harvesting them from the wild, planting and tending them. In the Middle East, they chose particular grasses – early forms of wheat; in China, wild dry rice; in Africa, sorghum; and in Papua New Guinea, the starchy tuber, taro.

For me, the most surprising thing about these new plants is that in their natural state you very often can’t eat them at all, or at least they taste pretty filthy if you do. Why would people choose to grow food that they can eat only once it’s been soaked or boiled or ground to make it digestible? Martin Jones, Professor of Archaeological Science at Cambridge University, sees this as an essential strategy for survival:

As the human species expanded across the globe, we had to compete with other animals going for the easy food. Where we couldn’t compete, we had to go for the difficult food. We went for things like the small hard grass seeds we call cereals, which are indigestible if eaten raw and may even be poisonous, which we have to pulp up and turn into things like bread and dough. And we went into the poisonous giant tubers, like the yam and the taro, which also had to be leeched, ground up and cooked before we could eat them. This was how we gained a competitive advantage – other animals that didn’t have our kind of brain couldn’t think several steps ahead to do that.

So it takes brains to get to cookery and exploit new sources of food. We don’t know what gender the cooks were who used our pestle to grind taro in New Guinea, but we do know from archaeological evidence in the Middle East that cookery there was primarily a woman’s activity. From examining burial sites of this period, scientists have discovered that the hips, ankles and knees of mature women are generally severely worn. The grinding of wheat then would have been done kneeling down, rocking back and forth to crush the kernels between two heavy stones. This arthritis-inducing activity must have been very tough, but the women of the Middle East and the new cooks everywhere were thereby cultivating a small range of nourishing basic foods that could sustain much larger groups of people than had been possible before. Most of these new foods were quite bland, but the pestle and mortar can also play a key part here in making them more interesting. The chef and food writer Madhur Jaffrey comments:

If you take mustard seeds, which were known in ancient times, and leave them whole they have one taste, but if you crush them, they become pungent and bitter. You change the very nature of a seasoning by crushing it.

These new crops and seasonings helped create new kinds of communities. They could produce surpluses which could then be stored, exchanged or simply consumed in a great feast. Our pestle’s long, thin elegant body looks far too delicate to have been able to withstand the vigorous daily pummelling of taro, so we should perhaps think of it more as a ritual, festive implement used to prepare special meals where people gathered, as we might do now, to trade, to dance or to celebrate key moments in life.

Today, while many of us travel freely, we depend on food grown by people who cannot move, who must stay on the same piece of land. This makes farmers across the world vulnerable to any change in climate, their prosperity dependent on regular, predictable weather. So it’s not surprising that the farmers of 10,000 years ago, wherever they lived, formed a world view centred on gods of food and climate, who needed constant placation and prayer in order to ensure the continuing cycle of the seasons and safe, good harvests. Nowadays, at a time when climate is changing faster than at any time for the past 10,000 years, most people in search of solutions look not just to gods but to governments. Bob Geldof is a passionate campaigner in this new politics of food:

The whole psychology of food, where it places us, is I think more important than almost any other aspect of our lives. Essentially, the necessity to work comes out of the necessity to eat, so the idea of food is fundamental in all human existence. It’s clear that no animal can exist without being able to eat, but right now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is clearly one of the top three priorities for the global powers to address. Upon their success or not will depend the future of huge sections of the world population. There are several factors, but the predominant one is climate change.

So another change in climate, like the one that around 10,000 years ago brought us agriculture in the first place, may now be threatening our survival as a global species.

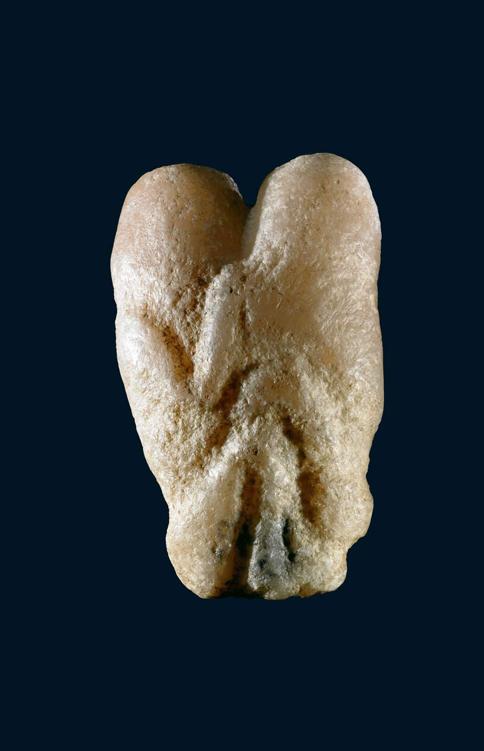

Ain Sakhri Lovers Figurine

9000

BC

As the latest Ice Age came to an end, somebody picked a pebble out of a small river not far from Bethlehem. It’s a pebble that must have tumbled downstream and been banged and smoothed against other stones as it went, in the process that geologists poetically describe as ‘chattering’. But about 11,000 years ago, a human hand then shaped and chipped this beautifully chattered, rounded pebble into one of the most moving objects in the British Museum. It shows two naked people literally wrapped up in each other. It’s the oldest known representation of a couple having sex.

In the Manuscripts Saloon at the British Museum, most people walk straight past the case that contains the carving of the lovers. Perhaps it’s because from a distance it doesn’t look like very much; it’s a small, muted, greyish stone about the size of a clenched fist. But when you get nearer to it, you can see that it’s a couple, seated, their arms and legs wrapped around each other in the closest of embraces. There are no clear facial features, but you can tell that these two people are looking into each other’s eyes. I think it’s one of the tenderest expressions of love that I know, comparable to the great kissing couples of Brancusi and Rodin.

At the time this pebble was shaped by human hands, human society was changing. As the climate warmed up across the world and people gradually shifted from hunting and gathering to a more settled way of life based on farming, our relationship to the natural world was transformed. From living as a minor part of a balanced ecosystem, we began trying to shape our environment, to control nature. In the Middle East the warmer weather brought a spread of rich grasslands. Until then people had been moving around, hunting gazelle and gathering the seeds of lentils, chickpeas and wild grasses. But in the new, lusher savannah, gazelle were plentiful and tended to stay in one place throughout the year, so the humans settled down with them. Once they were settled, they started gathering grass grains that were still on the stalk, and, by collecting and sowing these seeds, they inadvertently carried out a very early kind of genetic engineering. Most wild grass seeds fall off the plant and are spread easily by the wind or eaten by birds, but these people selected seeds which stayed on the stalk – a very important characteristic if a grass is to be worth cultivating. They stripped these seeds, removed the husks and ground the grains to flour. Later, they would go on to sow the surplus seeds. Farming had begun – and for over 10,000 years we’ve been breaking and sharing bread.

These early farmers slowly created two of the world’s great staple crops – wheat and barley. With this more stable life, our ancestors had time to reflect and to create. They made images that show and celebrate key elements in their changing universe: food and power, sex and love. The maker of the ‘lovers’ sculpture was one of these people. I asked the British sculptor Marc Quinn what he thought of it:

We always imagine that we discovered sex, and that all other ages before us were rather prudish and simple, whereas in fact – obviously – human beings have been emotionally sophisticated since at least 10,000

BC

, when this sculpture was made, and I’m sure just as sophisticated as us.What’s incredible about this sculpture is that when you move it and look at it in different ways, it changes completely. From the side, you have the long shot of the embrace, you see the two figures. From another side it’s a penis, from another a vagina, from another side breasts – it seems to be formally mimicking the act of making love as well as representing it. And those different sides unfold as you handle it, as you turn this object around in your hand, so they unfold in time, which I think is another important thing about the sculpture – it’s not an instant thing. You walk round it and the object unfolds in real time. It’s almost like in a pornographic film, you have long shots, close-ups – it has a cinematic quality as you turn it, you get all these different things. And yet it’s a poignant, beautiful object about the relationship between people.

What do we know of the people captured in this lovers’ embrace? The maker – or should we say the sculptor? – of the lovers belonged to a people that we now call the Natufians, who lived in a region that straddled what is today Israel, the Palestinian territories, Lebanon and Syria. Our sculpture came from south-east of Jerusalem. In 1933 the great archaeologist Abbé Henri Breuil and a French diplomat, René Neuville, visited a small museum in Bethlehem. Neuville wrote: