A Fortunate Man (13 page)

Authors: John Berger

Sassall, except when involved in the actual treatment of patients, is the most impatient man I know. He is incapable of waiting and doing nothing. He is incapable of resting. He sleeps easily but, at heart, he welcomes being called out at night. He finds it extremely hard to accept as normal the normal content of a day, an hour, a minute. His passion for knowledge is a passion for constructive experience with which to so fill his time that subjectively it becomes comparable with the âtime' of those in anguish. It is of course an impossible aim: to construct, to relieve, to cure, to understand, to discover with the same intensity per minute as those in anguish are suffering. Sometimes the aim, as it were, releases Sassall; but mostly he is its slave.

Unrealizable aims possess many men â all artists, for example. The special stress under which Sassall lives is the result of his isolation and his responsibility. He cannot, like artists, give himself up to his visions. He must remain observant, precise, patient, attentive. And, at the same time, he must face alone all the shocks and

confusion which have led to the aim. If he were working with colleagues he would never ask them: What is the value of a moment? Nor could any of them reply, if he did. But the question would present itself far less persistently. Their presence would automatically supply the professional context in which the implications of medical cases are strictly limited. As it is, the implications for Sassall can be almost limitless. What is the value of a moment?

I said that the price which Sassall pays for the achievement of his somewhat special position is that he has to face more nakedly than many other doctors the suffering of his patients and the sense of his own inadequacy. I want now to examine his sense of inadequacy.

There are occasions when any doctor may feel helpless: faced with a tragic incurable disease; faced with obstinacy and prejudice maintaining the very situation which has created the illness or unhappiness; faced with certain housing conditions; faced with poverty.

On most such occasions Sassall is better placed than the average. He cannot cure the incurable. But because of his comparative intimacy with patients, and because the relations of a patient are also likely to be his patients, he is well placed to challenge family obstinacy and prejudice. Likewise, because of the hegemony he enjoys within his district, his views tend to carry weight with housing committees, national assistance officers, etc. He can intercede for his patients on both a personal and a bureaucratic level.

He is probably more aware of making mistakes in diagnosis and treatment than most doctors. This is not because he makes more mistakes, but because he counts as

mistakes

what many doctors would â perhaps justifiably â call

unfortunate complications

. However, to balance such self-criticism he has the satisfaction of his reputation which brings him âdifficult' cases from far outside his own area. He suffers the doubts and enjoys the reputation of a professional idealist.

Yet his sense of inadequacy does not arise from this â although

it may sometimes be prompted by an exaggerated sense of failure concerning a particular case. His sense of inadequacy is larger than the professional.

Do his patients deserve the lives they lead, or do they deserve better? Are they what they could be or are they suffering continual diminution? Do they ever have the opportunity to develop the potentialities which he has observed in them at certain moments? Are there not some who secretly wish to live in a sense that is impossible given the conditions of their actual lives? And facing this impossibility do they not then secretly wish to die?

Sassall believes that adversity can temper character. But can their groping and sometimes blind unhappiness be called adversity?

What is the cause of boredom? Is boredom anything less than the sense of one's faculties slowly dying? Why do they have more virtues than talents? Who can deny that a culturally deprived community offers far fewer possibilities through sublimation than a culturally advanced one?

How much right have we to go on being always patient on behalf of others?

It is from questions such as these â and a hundred others that force their way up through the pauses between these questions â that the disquiet, which finally leads to Sassall's sense of inadequacy, first arises.

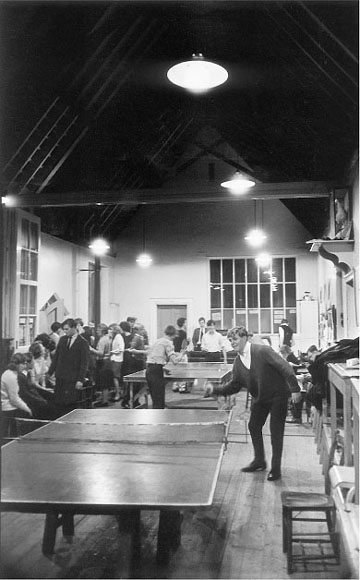

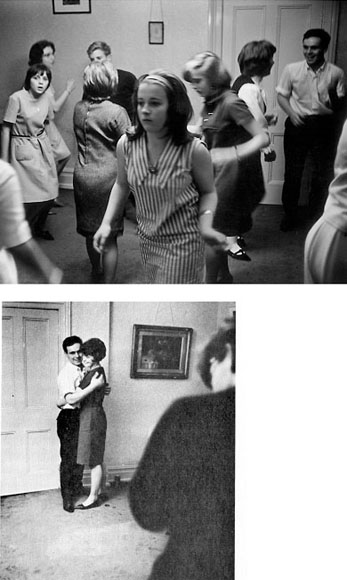

He argues with himself in an attempt to maintain his peace of mind. The foresters are not subject to the same frantic pressures as millions keeping up appearances in the suburbs. Families are less fragmented: appetites less insatiable: the standard of living of the foresters is lower but they have a greater sense of continuity. They may lack cultural opportunities individually: but collectively they have their Parish Council, their Moat Society, their Dart Teams, etc. These all encourage a sense of community. There is less loneliness in the Forest than in many cities. They are, as they might answer themselves, as happy as can be expected.

He refers the question back to his former self â the surgeon, the doctor of stark emergency, who tried to transform the foresters into Greek peasants. The foresters have no illusions about life, he says, only a small minority complain. Mostly they proceed with the business of living undaunted. They do not allow themselves â they cannot afford it â to be governed by their sensibilities. The notion of endurance is fundamentally far more important than happiness.

Abandoning his former self, Sassall now takes a realistic view of the world we live in and its brute indifference. It is the nature of this world that good wishes and noble protests seldom mitigate between the blow and the pain. For most of those who suffer, there is no appeal. The Vietnamese villages are burned alive though nine-tenths of the world condemns the crime. Those who rot in prison serving inhuman sentences which the jurists of the world declare unjust, rot nevertheless. Most crying wrongs cry until there are no more victims to suffer them. When once the blow is aimed at a man, little can come between it and the pain. There is a strict frontier between moral examples and the use of force. Once pushed over that frontier, survival depends upon chance. All those who have never been pushed that far are, by definition, fortunate and will question the truth of the world's brute indifference. All who have been forced across the frontier â even if they survive and return â recognize different functions, different substances in the most basic materials â in metal, wood, earth, stone, as also in the human mind and body. Do not become too subtle. The privilege of being subtle is the distinction between the fortunate and the unfortunate.

Yet however he argues, the disquieting questions return. And the harder he works, the more insistently they are posed. Whenever he makes an effort to recognize a patient, he is forced to recognize his or her undeveloped potentiality. Indeed in the case of the young or early-middle-aged it is often this which prompts the appeal for help â like the cry of a passenger who suddenly realizes that the vehicle in which he is travelling is not even going near

the destination he believed he was making for. If as a doctor he is concerned with the total personality of his patients and if he realizes, as he must, that a personality is never an entirely fixed entity, then he is bound to take note of what inhibits, deprives or diminishes it. It is the inwritten consequence of his approach.

He can argue that the foresters are in some respects fortunate compared to the majority of people in the world. But what is far more relevant to his own preoccupations is that he knows that the foresters are in almost all respects unfortunate compared to what they could be â given better education, better social services, better employment, better cultural opportunities, etc.

Talk of the âbad old days' before the war can encourage a certain superficial belief in progress. But faced with the young â and the prospects before them â it is hard to maintain any such belief. Sassall is forced to acknowledge that, by his own standards, they are having to settle for a fifth best.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

The situation by no means leaves him helpless. He can safeguard their health. Through the Parish Council he can urge improvements in the village. He can explain children to parents and vice versa. His word about a boy or a girl can carry some weight in the local schools. He can try to extend the meaning of sex for them. But the more he thinks of educating them â according to the demands of their very own minds and bodies before they have become resigned, before they accept life as they find it â the more he has to ask himself: by what right do I do this? It is not certain that it will make them socially happier. It is not what is expected or wanted of me. In the end he compromises â as the limitations of his energy would anyway force him to do; he helps in an individual problem, he suggests an answer here and an answer there, he tries to remove a fear without destroying the whole edifice of the morality of which it is part, he introduces the possibility of a hitherto unseen pleasure or satisfaction without extrapolating to the idea of a fundamentally different way of life.

I do not want to exaggerate Sassall's dilemma. It is one that many doctors and psychotherapists have to face: how far should one help a patient to accept conditions which are at least as unjust and wrong as the patient is sick? What makes it more acute for Sassall is his isolation, his closeness to his patients and a bitter paradox which we have not yet defined.