A Fortunate Man (11 page)

Authors: John Berger

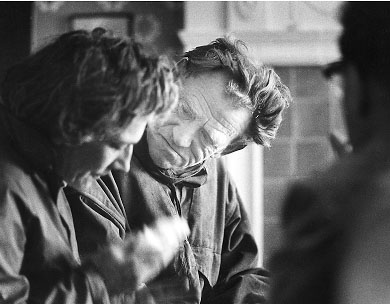

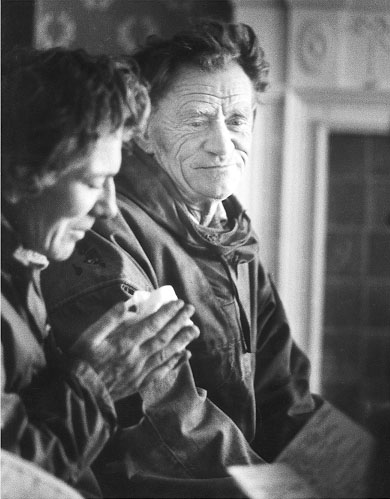

Sassall is not really alarmed by this, for he has established his own special position. As a result of this special position, however, he has to face, far more nakedly than many doctors, the suffering of his patients and the frequent inadequacy of his ability to help them.

It is generally assumed that doctors take a professional view of suffering and that the process of professional insulation begins in

their second year as medical students when they first start dissecting the human body. This is true. But the question is far deeper than overcoming any physical revulsion at the sight of blood or guts. Later, other factors are an aid to their self-protection. Doctors use a second, technical, entirely unemotional language. Frequently, they need to act quickly and to carry out complicated manual tasks which demand exclusive concentration. Increasing specialization encourages an increasingly scientific view of illness. (In the eighteenth century and earlier the doctor was often thought of as a cynic: a cynic is by definition a man who assumes a scientific âobjectivity' to which he has no claim.) The sheer number of their cases discourages self-identification with any individual patient.

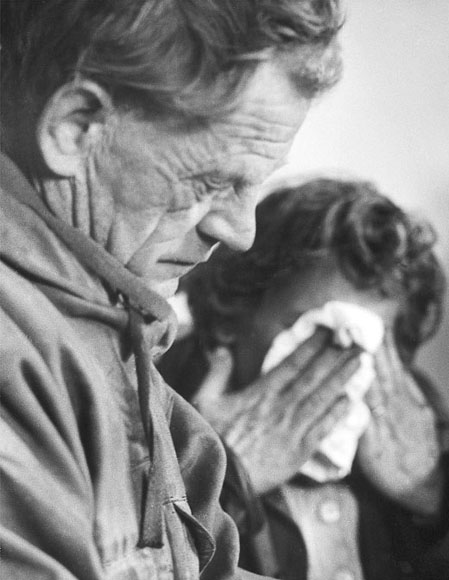

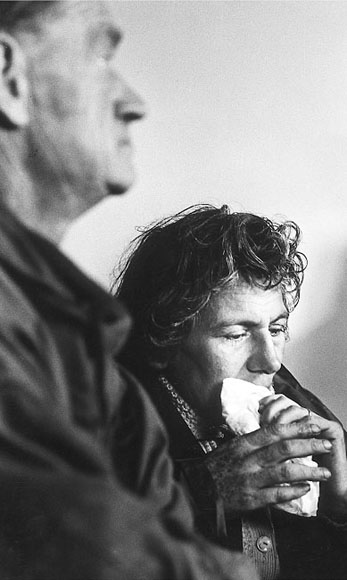

Yet, however true this may be, the suffering which certain doctors witness may be more of a strain than is generally admitted. This is so with Sassall. He is a man of extreme self-control. Nevertheless, when he was unaware of my presence, I saw him weep, walking across a field away from a house where a young patient was dying. Perhaps he was blaming himself for things done or left undone. He would transform his pain into a sense of painful responsibility, for that is his character.

But his sensibility is not just the consequence of his character: it is equally the consequence of his position and the way he practises. He never separates an illness from the total personality of the patient â in this sense, he is the opposite of a specialist. He does not believe in maintaining his imaginative distance: he must come close enough to recognize the patient fully. Although he has about 2,000 patients, he is aware of how they are all interrelated â and not only in the family sense â so that the numbers seldom acquire a statistical objectivity for him. Most important of all, he considers that it is his duty to try to treat at least certain forms of unhappiness. He very seldom sends a patient to mental hospital for he considers it a kind of abandonment.

What is the effect of facing, trying to understand, hoping to overcome the extreme anguish of other persons five or six times a week? I do not speak now of physical anguish, for that can usually be relieved in a matter of minutes. I speak of the anguish of dying, of loss, of fear, of loneliness, of being desperately beside oneself, of the sense of futility.

One aspect of the confrontations seems to me to be important and not much discussed, and so the reader must forgive me if I concentrate on this and ignore others.

Anguish has its own time-scale. What separates the anguished person from the unanguished is a barrier of time: a barrier which intimidates the imagination of the latter.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

A man or a woman who is sobbing reminds one of a child, but in the most disturbing way. This is partly because of the particular social convention which discourages adults (and particularly men) from breaking into tears but permits children to do so. Yet this is by no means the whole explanation. There is a physical resemblance between a sobbing figure and a child. The âbearing' of the adult falls away and his movements are limited to certain very primitive ones. The centre of the body once again seems to be the mouth: as though the mouth were simultaneously the place of pain and the only way by which consolation might be taken in. There is a loss of the control of the hands which again can only clench or paw. The whole body tends towards a foetal position. There are good physiological and psychological reasons for all this: but we can observe the similarity without knowing them. And why is the similarity so disturbing? Once more I believe the explanation goes further than our sense of convention or compassion. In some way the similarity, once established, is brutally denied. The sobbing man is not like a child. The child cries to protest. The man cries to himself. It may even be that by crying again like a child he somehow believes that he will regain the ability to recover like a child. Yet that is impossible.

Â

Â

Â

Anguish need not necessarily involve weeping. It may be composed more bitterly in hatred, vengeance or in that half-mocking anticipation of cruelty with which the desperate sometimes await their own destruction. But all anguish, whatever its expression of cause and whether it is rational or neurotic, returns the sufferer to a childhood which increases his despair. Or at least that is what I believe as a result of my own observation and introspection.

It is a platitude that as we grow older time seems to pass more quickly. The remark is usually made nostalgically. But we seldom consider the contrary effect of the same process â the elongation of time as it must affect the young and very young. The young themselves can say little about it, because they only have a standard of judgement when they become aware of time changing its pace and by then it's too late for any direct evidence. If we knew how long a night or a day was to a child, we might understand a great deal more about childhood. Could it not be that the deeply formative nature of early childhood experience is due not only to the force of its impact (a force measured by the child's relative weakness) but also to the fact that by the child's own reckoning the experiences continue for so long? It may be that, subjectively, a childhood is at least equal in length to the rest of a lifetime. The phenomenon of old people, when their daily practical preoccupations are reduced to a minimum, remembering more and more clearly more and more about their childhood may confirm this; subjectively, their childhood was perhaps most of their life.

Yet why should time seem to change its pace? What is the difference between a child and an adult in this respect? Sartre in his first novel

5

offers a clue. The book as a whole is partly concerned with a similar and parallel problem: how to achieve a sense of adventure given a full awareness of the nature of time. This is how he describes the habitual life of the adult.

When you are living, nothing happens. The settings change, people come in and go out, that's all. There are never any beginnings. Days are tacked on to days without rhyme or reason, it is an endless, monotonous addition. Now and then you do a partial sum: you say: I've been travelling for three years, I've been at Bouville for three years. There isn't any end either: you never leave a woman, a friend, a town in one go. And then everything is like everything else: Shanghai, Moscow, Algiers, are all the same after a couple of weeks. Occasionally â not very often â you take bearings, you realize that you're living with a woman, mixed up in some dirty business. Just for an instant. After that, the procession starts again, you begin adding up the hours and days once more. Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday. April, May, June. 1924, 1925, 1926.

Sartre contrasts this âliving' with the occasional âfeeling of adventure'. This feeling need have nothing to do with exciting events. It is a form of heightened awareness giving a sensation of order â and therefore of meaning â to the very fact and limitations of existence.

This feeling of adventure definitely doesn't come from events: I have proved that. It's rather the way in which moments are linked together. This, I think, is what happens: all of a sudden you feel that time is passing, that each moment leads to another moment, this one to yet another and so on; that each moment destroys itself and that it's no use trying to hold back, etc., etc., and then you attribute this property to the events which appear to you

in

the moments; you extend to the contents what appertains to the form â¦

If I remember rightly, they call that the irreversibility of time. The feeling of adventure would simply be that of the irreversibility of time. But why don't we always have it?

The irreversibility of time is something that young children are well aware of, although the concept could mean nothing to

them. They live with it. There are no inevitable repetitions in childhood. âMonday, Tuesday, Wednesday. April, May, June. 1924, 1925, 1926' represents the antithesis of their experience. Nothing is bound to repeat itself. Which, incidentally, is one of the reasons why children ask to be reassured that some things will be repeated. âAnd tomorrow I will get up and have breakfast?' Gradually after the age of about six, they can answer the question for themselves and they begin to expect and depend upon cycles of events; but even then their unit of measurement is so small â their impatience, if you wish to call it that, is so great â that the foreseen still seems too far off to qualify the present to any important degree: their attention still remains on the present in which things constantly appear for the first time and are constantly being lost for ever.

One of the most widespread adult illusions is the belief in second chances. Children, until they are otherwise persuaded or bribed by adults, know that they do not exist. Their necessary self-abandonment to experience makes it impossible for them to entertain such an idea. The adult belief in them is a double buffer against experience. Not only is everyone given countless second chances, but the uniqueness of every event is blurred over, if not destroyed. And so, as time goes on, or rather fails to go on, we can tentatively propose that the world has become familiar with us, even that the world on the basis of past events is our debtor. Children have no need for such protection.