A Fortunate Man (8 page)

Authors: John Berger

I am not, of course, implying that Sassall is an historically comparable figure to Paracelsus. But I suspect that he is in the same vocational tradition. There are doctors who are craftsmen, who are politicians, who are laboratory researchers, who are ministers of mercy, who are businessmen, who are hypnotists, etc. But there are also doctors who â like certain Master Mariners â want to experience all that is possible, who are driven by curiosity. But âcuriosity' is too small a word and âthe spirit of enquiry' is too institutionalized. They are driven by the need to know. The patient is their material. Yet to them, more than to any doctor in any of the other categories, the patient, in his totality, is for that very reason sacred.

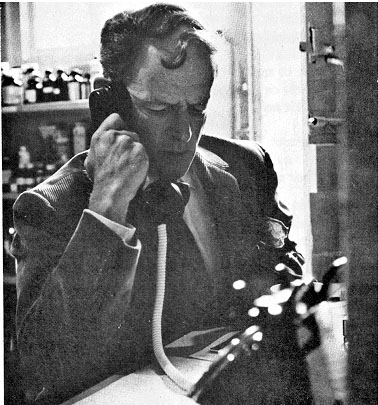

When patients are describing their conditions or worries to Sassall, instead of nodding his head or murmuring âyes', he says again and again âI know', âI know'. He says it with genuine sympathy. Yet it is what he says whilst he is waiting to know more. He already knows what it is like to be this patient in a certain condition: but he does not yet know the full explanation of that condition, nor the extent of his own power.

In fact no answer to these open questions will ever satisfy him. Part of him is always waiting to know more â at every surgery, on every visit, every time the telephone rings. Like any Faust without the aid of the devil, he is a man who suffers frequently from a sense of anti-climax.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

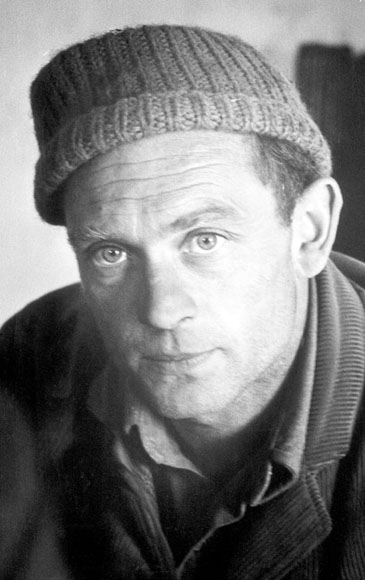

This is why he exaggerates when he tells stories about himself. In these stories he is nearly always in an absurd position: trying to take a film on deck when the waves break over him; getting lost in a city he doesn't know; letting a pneumatic drill run away with him. He stresses the disenchantment and deliberately makes himself a comic little man. Disguised in this way and forearmed against disappointment, he can then re-approach reality once more with the entirely un-comic purposes of mastering it, of understanding further. You can see this in the difference between his two eyes: his right eye knows what to expect â it can laugh, sympathize, be stern, mock itself, take aim: his left eye scarcely ever ceases considering the distant evidence and searching.

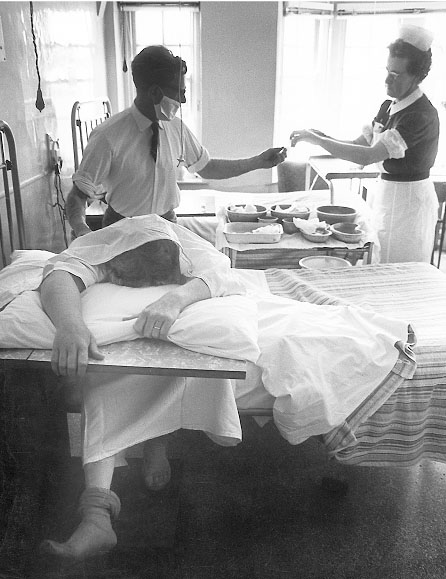

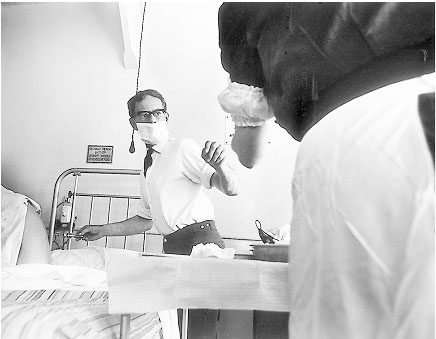

I say scarcely ever, but there is one exception. This is when he is occupied with some relatively minor surgical task. He may be setting a fracture in his surgery, or attending to one of his patients in the local hospital. On these occasions both eyes concentrate on the task in hand and a look of relief comes over his face. As soon as he takes his coat off, rolls up his sleeves, washes his hands, puts on gloves or a mask, this relief is apparent. It is as though his mind is wiped clean (hence the relief) in order to concentrate exclusively on the limited operation in hand. For a moment there is certainty. The job can be done well or badly: the distinction between the two is beyond dispute: and it must be done well.

I saw a similar expression on the face of a farmer who lives only a few miles from Sassall. This farmer is mad about flying and owns a six-cylinder open-cockpit Czech plane. His farm is not a large or particularly prosperous one. Nor is he part of the gentry. He lives by himself and likes speed. He keeps the plane under an oak-tree in one of his fields. When we had driven the sheep to the other end of the field, and I had turned the prop and he and Jean Mohr were settled and the engine was warm, he signalled to me to let go of the tip of the wing â I was holding it for the plane had no brakes â and at that moment, just before they took off, although there was a gusty wind blowing and the field was very rough and the take-off was liable to be quite tricky, I saw exactly the same look of relief pass over the farmer's unshaved, chunky, middle-aged face. The problems now were limited to aerodynamics and the functioning of a small internal-combustion engine: the problem of prices, mortgages, Monday's market, relations, reputation, would all in a moment be beneath them.

The difference between the farmer and Sassall is that the farmer would like to be able to spend all his life blithely flying and gliding â or anyway believes that he would; whereas Sassall needs his unsatisfied quest for certainty and his uneasy sense of unlimited responsibility.

So far I have tried to describe something of Sassall's relationship with his patients. I have tried to show why he is thought of as a good doctor, and how being âa good doctor' answers some of his own needs. I have suggested something of the mechanism by which he cures others to cure himself. But all this has been on an individual basis. We must now consider his relationship to the local community as a whole. What do his patients expect of him publicly when they are not ill? And how does this relate to their barely formulated expectations of fraternity within the privacy of illness?

Sassall lives in one of the larger houses of the village. He is well dressed. He drives a Land Rover for his practice, and another car for his private use. His children go to the local grammar school. Without any doubt at all the part allotted him is that of

gentleman

.

The area as a whole is economically depressed. There are only a few large farms and no large-scale industries. Fewer than half the men work on the land. Most earn their living in small workshops, quarries, a wood-processing factory, a jam factory, a brickworks. They form neither a proletariat nor a traditional rural community. They belong to the Forest and in the surrounding districts they are invariably known as âthe foresters'. They are suspicious, independent, tough, poorly educated, low church. They have something of the character once associated with wandering traders like tinkers.

Sassall has done his best to modify the part of gentleman allotted him, and has partly succeeded. He leads almost no social life of his own â except in the village with the villagers. It is when he is talking with his few middle-class neighbours that one is most aware of his own class background. This is because they assume in conversation and attitude that he shares their prejudices. With the âforesters' he seems like a foreigner who has become, by request, the clerk of their own records.