A Companion to the History of the Book (42 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

The Book Trades

The book trade had a multiplicity of specializations. If the pressmen and compositors are the most obvious, behind them we find punch-cutters and type-founders, ink-makers and papermakers, all developing into quite distinct crafts by the mid-century Sale of the output of the presses required the services of bookbinders and of booksellers, and more often than not a distribution network, especially for scholarly works in Latin, which required an international market to recover their costs. In the first half of the century, Parisian printers produced books for distribution in many provincial towns (especially Lyon and Rouen) as well as abroad (for example, London and Louvain). Already by the early years of the century, the dominant figure in the book trade was the

marchant libraire

or merchant bookseller, what we would call today a publisher and wholesaler. Even a major figure such as Aldus Manutius needed backers who provided financial support for his operations. Some of these financiers operated on a European scale, such as Anton Koberger in Nuremberg or the Giunti family in Venice or Jean Petit in Paris. As has already been mentioned, the major fairs provided the opportunity for publishers and booksellers to meet, place orders, and settle accounts.

The importation of books was usually subjected to control by the state authorities to guard against the introduction of religious or politically seditious works. The inevitable consequence was that such texts would be smuggled: there were cases of smuggling Lutheran writings into East Anglia in the 1520s and 1530s; printers in Geneva set up extensive networks for getting Calvinist works to their markets in the Protestant communities in France; at the end of the century, Catholic texts were produced by presses in Douai and Rouen for distribution to recusant communities both in England and on the continent. In Spain, it is generally believed that excessive censorship caused stagnation in the book trade by the mid-century.

Customers

Authors in sixteenth-century Europe had few rights. They owned their copyright so long as they held the only copy of their work. To get a new work printed, they had to persuade a bookseller or a printer to invest capital, labor, and materials in its production. This would frequently involve paying some or all of the costs in return for a share in the copies printed. Increasing numbers of contracts of this sort have been formed from this period, typically specifying payment for the cost of paper (Richardson 1999: 58–69).

Purchasers of books dealt with a retail bookseller, as today, either in person or by correspondence. The title page of a book would typically state the address of its publisher, and customers no doubt knew who specialized in what. In Paris in the first half of the century, scholarly texts might be bought from Henri Estienne at the Sign of St. John the Baptist opposite the Law Schools or from Gilles de Gourmont at the Sign of the Three Crowns on the rue Saint Jacques. Simon Vostre specialized in Books of Hours at the Sign of St. John the Evangelist on the rue Neufve Nostre Dame. In London and in Paris, the booksellers and printers tended to congregate in one area, the university quarter in Paris, and St. Paul’s Churchyard in London. In the provinces, a customer would get a local bookseller to order from a supplier in the capital or might get a relative there to buy for him.

Who bought books? A lot can be deduced from the range of titles produced. Three-quarters of the books published in the fifteenth century were in Latin; by the end of the sixteenth century, over half were in the vernacular languages (Hirsch 1967: 132). This indicates that a large proportion of book buyers still belonged to the educated and professional classes who had learned Latin at school and university: doctors, lawyers, clerics, teachers, as well as those from well-to-do families who had received a similar education. Nevertheless, the growing proportion of books in the vernacular languages shows the growth of literacy in the general population, especially in urban areas in Protestant countries which put a high value on the ability to read the Bible.

How much did a customer have to pay for a printed book? In mid-sixteenth-century England, the popular pamphlet-sized

A lytell geste of Robin Hood

cost two (old) pence, whereas Chaucer’s

Works

cost five shillings bound or three shillings unbound (Bennett 1950: 176–7). Inflation was, of course, a constant factor at this time and it is difficult to relate prices to wages. Clearly, books did sell and in considerable quantities. For the first time, a living author could become aware that he had access to a far wider public than his immediate circle of patrons. Clément Marot,

valet de chambre

and royal poet to King François I, was also a bestseller: his

Adolescence Clementine

went through about forty editions between its first appearance in 1532 and 1538 when he published his collected poems, which had gone through a further twenty editions by the time of his death in 1544.

Look to the Future

Just as the book trade in 1501 was not radically different from that in 1499, so the advent of the seventeenth century would not bring an immediate change in trends. The academic world still needed a good range of classical and religious texts; religious controversies continued to flourish; literacy continued to spread and the proportion of Latin books continued to decline. The economics of the printing trade favored the rise of consortia of booksellers such as the Compagnie de la Grand’ Navire in Paris (1585–1641), forming what we would consider to be a publishing company specializing in the financing of editions of the Church Fathers. Scientific and reference publishing was not unknown in the sixteenth century (Nicolaus Copernicus’s

De

revolutionibus

was first published in 1543) but was to see a great increase in the next century as the scientific revolution progressed. Similarly, the demand for news books would develop strongly but was not unknown during the upheavals of the Wars of Religion. Newspaper publication, however, was still for the future.

References and Further Reading

Armstrong, E. (1986)

Robert Estienne, Royal Printer: An Historical Study of the Elder Stephanus,

rev. edn. Abingdon, Berkshire: Sutton Courtenay Press.

Barnard, J., McKenzie, D. E, and Bell, M. (eds.) (2002)

The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain,

vol. IV:

1557–1695.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bennett, H. S. (1950) “Notes on English Retail Book-prices, 1480–1560.”

The Library,

5th ser., 5: 172–8.

Clair, C. (1960)

Christopher Plantin.

London: Cassell (reprinted London: Plantin, 1987).

— (1976)

A History of European Printing.

London: Academic.

Febvre, L. and Martin, H-J. (1976)

The Coming of the Book,

trans. D. Gerard. London: Verso (reprinted 1997; originally published 1958).

Gilmont, J-F. (ed.) (1998)

The Reformation and the Book,

trans. K. Maag. Aldershot: Ashgate (originally published 1990).

Goldschmidt, E. P. (1943)

Medieval Texts and their First Appearance in Print.

London: Bibliographical Society.

Hellinga, L. and Trapp, J. B. (eds.) (1999)

The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain,

vol. III:

1400–1557.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hirsch, R. (1967)

Printing, Selling and Reading, 1450–1550.

Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

McKitterick, D. (2003)

Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450–1830.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rabelais, F. (1955)

Gargantua and Pantagruel,

trans. J. M. Cohen. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Richardson, B. (1999)

Printing, Writers and Readers in Renaissance Italy.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, M. M. (2000)

The Title-page: Its Early Development 1460–1510.

London: British Library.

Steinberg, S. H. (1996)

Five Hundred Years of Printing,

rev. John Trevitt. London: British Library.

17

The British Book Market 1600–1800

John Feather

The World of the Book

In 1600, Elizabeth I sat on the throne of England, as she had done for more than forty years. During her reign, the kingdom had faced many great challenges, not least of which was that from a foreign power – Spain – which had tried and failed to invade and conquer. The queen’s armies were still fighting in Ireland to try to bring that rebellious kingdom more fully under her control. In Scotland, James VI reigned over – and sometimes ruled – a kingdom that was less stable than its southern neighbor. He looked forward to the day (which was to come in 1603) when he would inherit the English crown to add to his own.

In 1800, George III was monarch of a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; in Ireland there were simmerings of revolt, but Scotland had been pacified after the failure of the rebellion of 1745. His people had won an empire in North America and India, lost part of it in 1776, and were beginning to build yet more colonies in the remote southern oceans. The great challenge was again from abroad, but this time from France which, under Napoleon, controlled virtually the whole of continental Europe and was actively planning an invasion of Britain. During the two hundred years between the reigns of Elizabeth I and George III, the political, social, intellectual, and cultural life of the British underwent great change. In 1800, even greater changes were becoming apparent; in the England of George III, new industries and new skills were remaking social and economic relationships and were causing the development of a different kind of society. It is against this background of profound and continuing change that we have to see the little world of the book.

At the turn of the seventeenth century that world was paradoxically both narrow and wide. It was narrow in the sense that the production of books in England was, for all practical purposes, confined to a small and closely knit group of booksellers and printers in London. It was wide in the sense that the London book trade (and the handful of printers in Scotland), although it produced books almost entirely in English, also dealt with books in Latin – still the principal written language of the learned elite - that were imported from elsewhere in Europe. The “Latin trade,” as contemporaries called it, is always part of the context of the early-modern book trade in Britain; its existence explains why scholarly publishing developed only slowly in the British Isles, even in the universities, and why the native trade was inward-looking both linguistically and geographically (Roberts 2002). The positive consequence was that the London book trade had a near-monopoly of the trade throughout England; there was slightly greater diversity in Scotland, but in a much smaller market. In 1600, the Irish trade was negligible, as was the Welsh trade.

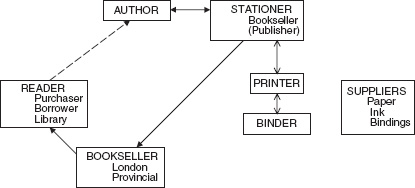

Figure 17.1

The circuit of the book.

The “book trade,” however, is not a simple entity; it is a complex concatenation of trades and activities involving many players. The American historian Robert Darnton has developed the concept of the “circuit” of the book as a means of modeling these relationships (Darnton 1982, 1990). His approach has the merit of showing the connections between author and reader of which the book trade is merely the facilitator. A version of this circuit, using twenty-first century terminology, is given in

figure 17.1

. The principles embodied in the concept of the circuit have remained essentially unchanged since the sixteenth century; the players, however, have been through major transformations. In

figure 17.2

the circuit concept is adapted to represent the English book trade in 1600.

The most important difference between the contemporary and early-modern models lies in the division of roles and skills between the various players involved in the trade. Nevertheless, it remains the case that at the heart of the printed book trade there is a person or firm which turns the author’s work into a form in which it can be distributed and sold. Since the early nineteenth century, this functionary has been called the publisher, but long before the word was used in this sense the functions which it describes were central to the trade. In the early seventeenth century, the term used was “bookseller” or sometimes (but perhaps already rather old-fashioned) “stationer.” We should confuse none of these terms with their modern equivalents. The seventeenth-century bookseller (the word which will be used here) did indeed sell books to the general public but he (rarely she, although there was an increasing number of women in the trade) might also be a publisher, a wholesaler, and a distributor. Sometimes – but less commonly after about 1600 – all of this was combined with printing and perhaps bookbinding. During the early seventeenth century, however, the separation of printing from the other functions was largely completed, at least in London. In Ireland and Scotland it remained common throughout the seventeenth century for a single business to combine all the functions of the trade, and when printing was allowed to develop in English provincial towns from the mid-l690s onward, it continued to be the normal practice for printers to sell and bind books, and occasionally even to publish them, as well as being printers and (in the modern sense) stationers. The final separation between booksellers and publishers (again using both words in the modern sense on this occasion) did not begin to happen until the last quarter of the eighteenth century, and only then do we find a handful of pioneers coming into the trade specifically to publish books.

Figure 17.2

The book trade in the early seventeenth century.

Authors: The Primary Producers of the Book Trade

Everything that is printed and published has been written by someone. His or her identity may be concealed, disguised, or forgotten, but there is a human intelligence behind every word that has ever been put into print. The idea of the author as creative genius is a comparatively modern concept, a product of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Romanticism. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, no such romantic notions prevailed. Authors wrote, as they always have, from a variety of motives: to persuade, to advance their careers, to say something they thought was worth saying, to give pleasure to themselves and perhaps to others, to make money. By 1600, the idea of writing for reputation and perhaps for money was no longer as unusual as it had been even within living memory. It was the development of the trade in printed books that had made this possible. For as long as books were written by hand, comparatively few copies could be put into circulation, and there was little chance of recouping significant sums of money from their sale. Authors “published” their work by allowing a scribe to copy it, and perhaps received a one-off payment from a patron for their trouble (Woudhuysen 1996). The development of a trade in printed books at the end of the fifteenth century increased the demand for new books as well as for printed versions of older ones. To meet this demand, authors were employed by printers to create books by editing existing texts or by composition. As the dominant role in the London book trade passed from printers to booksellers in the second half of the sixteenth century, so too did the initiative for developing new books and dealing with authors.

By the last quarter of the seventeenth century, writing for money – what came to be called “writing for the booksellers” – was an established, although far from respectable, occupation. A handful of such writers from every generation are remembered, usually because they were distinguished in other fields, or because they were writers of exceptional skill or interest. The financial rewards were comparatively small. The bookseller bought the book from the author, and the author’s financial interest in it came to an end at that moment. The word which contemporaries used for what was bought was “copy,” derived from the use of the word by printers to mean the manuscript followed by the compositor in setting the type. Even before 1600, there was an assumption in the book trade, reinforced by custom and in due course by law, that when a bookseller bought a copy, he or she had the unique right to print it or cause it to be printed. One consequence of this assumption was the evolution of the law of copyright (see chapter 38); another was the recognition of the author’s role as the initiator of a chain of commercial transactions. By 1700, it was recognized in practice that when the bookseller bought a copy, the author was selling a product that he or she had created, and that the “rights” therefore originated with the author.

This was recognized in the first British Copyright Act (1710). Very soon, a few authors were exploiting the Act for their own benefit, manipulating the sale of their rights to give themselves some measure of control over the finished product. Alexander Pope was particularly adept at this. From about 1720 until the end of his life (he died in 1744), he exploited the book trade much more than it exploited him. In a reversal of traditional roles, he was the financial supporter – the patron – of a printer and a bookseller, and gave significant help to others in the trade. In return, he made demands on them about the physical appearance of his works, and insisted on payments that related to the number of copies sold and the number and form of reprints rather than simply accepting a single payment for the outright sale of his rights. No other eighteenth-century English authors (and few since) were able to exercise such control over the publication of their works. Pope’s unique achievement was, however, of wider importance: he established that the author was a partner in the process of book production, and that the new law of copyright could be used to help authors as well as booksellers (Feather 1994).

During Pope’s lifetime there were other developments which put authors in a more favorable position. The most important of these was the rapid development of newspapers and magazines. News books had existed before 1640, and proliferated during the Civil War (1642–9), but from 1650 until the Restoration (1660) they were tightly controlled, and effectively published by government. Under the 1662 Printing Act, pre-publication censorship of all printed matter, and the restriction of printing to London and (in a very limited way) Oxford, Cambridge, and York, meant that the newspaper press was again carefully controlled. Indeed, for some time after 1665 the only legal newspaper was the official

London Gazette.

During the 1670s, however, new titles did begin to appear, and from the mid-l690s onward they proliferated. The first London daily,

The Daily Courant,

began publication in 1702; the first provincial newspaper, the weekly

Norwich Post,

began publication in 1701. During the reign of Queen Anne (1702–14), party political strife was rampant; newspapers appeared on every side, sometimes subsidized by political leaders, including those in government. The first great English journalist, Daniel Defoe (1660–1731), learned his trade as a writer during this time, while also working as a government agent and spy. He was later to put his skills to other uses in

Robinson Crusoe

(1719) and

Moll Flanders

(1722).

Defoe was not the only writer to emerge form the journalistic maelstrom of early eighteenth-century politics. Joseph Addison (1672–1719) and Richard Steele (1672–1729), both active politicians, worked together on a journal which they founded, and whose name still survives:

The Spectator.

Each of the more than five hundred issues published in 1711 and 1712 consisted of a single extended essay on some social or political theme.

The Spectator

was a commercial success from the start, and it became a classic. In book form, the essays were reprinted in scores of editions throughout the eighteenth century and later, while Addison and Steele both continued to have parallel literary and political careers. The essay periodical itself became a well-established format for eighteenth-century magazines. Among those who benefited was Samuel Johnson (1709–84) whose

Rambler

(1750–2) and

Idler

(1758–60) imitated both the format and the commercial and literary success of

The Spectator.

Unlike Addison and Steele, however, Johnson was entirely dependent on his pen for his living for much of his life. His essay periodicals were written for the booksellers and were a straightforward commercial transaction. It was a measure of how far authors had come in less than fifty years.