A Companion to the History of the Book (19 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

The earliest books in China were not readily available throughout society. Chinese social and educational customs, habits of memorization and recitation of texts, traditions of discourse, and the cost and availability of materials all militated against the wide dissemination of books at first. Early manuscript libraries in China were chiefly institutional: they held official records, documents, and dispatches that appear to have been the exclusive property of archivists, teachers, and military or civil officials, or rather of the institutions that those persons served. From the time of Confucius (551–479

BC

), however, the appearance of numerous schools of philosophy, as well as the study of military affairs, cartography, astronomy, and medicine, resulted in new categories of books. Diversified production of books eventually led to broader consumption, and finally to personal book collections.

The origin of classified book catalogues in China can be traced as far back as the Han dynasty. The

Hanshu yiwenzhi

(Bibliographical Section of the History of the Former Han, 206

BC

–

AD

24) by Ban Gu (

AD

32–92) was based on two earlier catalogues and is a reflection of the restoration of the Han imperial library in response to the infamous “book burning” by the emperor Shi Huang of the Qin dynasty (221–206

BC

). Ban Gu’s catalogue of some six hundred works provides a clear picture of the prevailing diversity of books. The ratio of bamboo and wooden strip books to silk rolls is about three to one. Despite evidence of increased private possession of books, beginning from the Warring States period, true democratization of the book awaited the greater availability of paper. From the Han period onward, the dynastic histories cite an increasing number of persons with collections of books.

By the Sui dynasty (581–618), after a few centuries of turmoil, manuscript book collecting had developed in China. The bibliographical section of the

Suishu

(History of the Sui Dynasty), completed in 656, is significant because it uses the four-part classification scheme (classics, history, philosophy, and literature) that continued to dominate book catalogues throughout the imperial era. Ink-squeeze rubbings from stone inscriptions, a form of proto-printing, are also included. An appendix contains books on Buddhism and Daoism. The steady introduction, translation, and compilation of Buddhist texts grew into a substantial canon. From the Tang and Five dynasties (907–960), Buddhist manuscript libraries grew rapidly. More than 30,000 manuscript scrolls were discovered in the Dunhuang grottoes at the turn of the twentieth century, the largest existing body of early manuscripts on paper, and the majority of them are Buddhist. They are dated from the fourth to the tenth century and provide a valuable source for the study of early Buddhist libraries (Drège 1991; Tsien 2004).

Despite the conspicuous advance of printing in the Song, collections of manuscripts were not suddenly eclipsed by printed books. For one thing, conservative scholars were skeptical of the textual quality of the impersonal printed products; for another, good-quality books were rather expensive. No matter the rapid growth of printing, many desirable titles were not in print and could only be obtained by making manuscript copies. By the end of the twelfth century, the imperial library in Hangzhou possessed several thousand titles, but it is estimated that only one-quarter were printed books. The social significance of calligraphy training, the practice of sutra copying by Buddhists, the belief that “the best way to read a book is to copy it,” as well as traditions of handwritten annotation and textual collation, all contributed to the general prevalence of manuscript books in traditional China. The chief kinds were

gaoben

or

shou gaoben

(original manuscript or holograph),

qing gaoben

(clean copy of an original manuscript),

chaoben

or

xieben

(copied manuscript from a printed or handwritten source), and

ying chaoben

(facsimile manuscript).

Diben

was the source copy for a copied manuscript or facsimile manuscript, and

jiaoben

was a collated or annotated copy of a manuscript or printed book.

Imperially sponsored projects on a grand scale in the Ming and Qing periods further emphasized the importance of manuscripts. In 1403, the Yongle emperor (r. 1403–24) commissioned the voluminous classified encyclopedia of citations from known literature, the

Yongle dadia n.

It comprised nearly 23,000

juan

(chapter-like sections) of text bound in more than 11,000 folio-size volumes. It is reported that no less than 3,000 scholars and scribes consulted about 8,000 works covering many subjects and took several years to finish the task. Too vast to be printed, the manuscript compilation was stored in the imperial library.

In the eighteenth century, the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–95) expanded the palace book collections, and he is best known for having created the

Siku quanshu

or Four Libraries collection. This manuscript repository comprises about 3,500 individual works in 36,000 volumes, stored in 6,000 individual boxes made of

nanmu

wood. It was edited and transcribed between 1773 and 1782 by a board of more than 350 eminent scholars and countless court scribes. Rare printed works and manuscripts were solicited from all over the country to serve as

diben

, and more than 10,000 works were reviewed for consideration. The resulting bibliographical descriptions for 10,254 titles were published in 1782 in 100 volumes as the

Qinding siku quanshu zongmu

, which still remains the most comprehensive Chinese descriptive bibliography. No matter that one of the emperor’s undisclosed aims in soliciting all these titles was to compile a list of proscribed works to censor, the main thrust of the effort was to preserve an extensive body of literature.

Between 1782 and 1787, seven identical sets of the Four Libraries collection were produced in manuscript on the emperor’s orders, to be deposited in seven library buildings erected between 1775 and 1784. The first four sets were designated for the imperial palace and three detached palaces in the north; the remaining three were to be placed in Zhenjiang, Yangzhou, and Hangzhou in the south. The magnitude of the project will be apparent if we realize that it produced a total of more than 250,000 uniformly written manuscript volumes. Three of the original buildings and manuscript collections wholly exist today, and a fourth survives thanks to considerable restoration.

That the invention of printing took place at all in China in the early Tang dynasty has to be seen as the direct result of the availability of paper, which existed as part of a widespread literate culture. Once high-quality paper was available for manuscript production, then impressions could be taken from inked seals and small wooden pictorial stamps, and ink-squeeze rubbings of text could be made from stone inscriptions. These simple means of duplicating word and image evolved into the use of carved wooden blocks (xylography) to print multiple copies of complete texts.

The enormous qualified labor force (especially block-cutters) available to the Chinese publishing industry insured a steady flow of books and printed matter over many centuries. The widespread locations of commercial publications are clearly recorded in the colophons of Southern Song (1127–1279) printed books. In addition to the well-known body of orthodox books produced for the educated elite, an abundance of popular publications circulated among the semiliterate: religious tracts, almanacs, storybooks, theatrical and musical texts, practical handbooks, artisan pattern books, and textbooks for children as well as for townsmen who needed to learn new skills, such as accounting, not to mention a wide variety of single-sheet posters, playbills, announcements, and new year and festival prints.

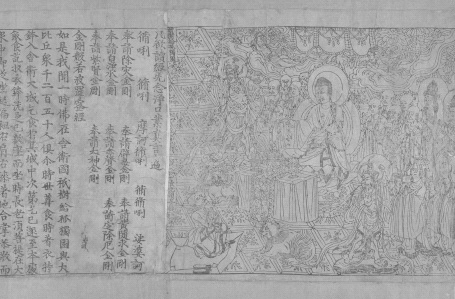

Most examples of pre-Song Chinese printing that we have today are from Dunhuang, where they were found together with the considerable storehouse of early manuscripts. That they are mostly regional products and Buddhist in content has prejudiced our view of early Chinese imprints. The most important specimen is the

Jin’gang jing

(Diamond Sutra) of 868, a unique example in the British Library and renowned as the world’s oldest complete printed book (

figure 7.2

). It is printed on six large sheets of hemp paper, pasted on end to form a scroll about 25 cm high and over 5 m long, with an impressive frontispiece woodcut, which shows Shakyamuni seated on a lotus throne behind an altar table, surrounded by disciples and heavenly figures, facing the aged Subhuti, who genuflects on a mat. In the printed colophon at the end of the text it is clearly stated that “On the fifteenth day of the fourth month of the ninth year of the Xiantong reign [11 May 868], Wang Jie, in honor of his parents, respectfully had this sutra printed for universal dissemination.”

Figure 7.2

Frontispiece woodcut and initial lines of text of the

Jin’gang jing

(Diamond Sutra), printed in 868 and bound in scroll book form. Reproduced by courtesy of the British Library (Or.8210/P.2).

As printing matured in the tenth and eleventh centuries, innovations were introduced and some large-scale projects were carried out. The tenth century saw publication of the first woodblock edition of the canon of Confucian classics, followed by various dictionaries and other secular books. The

Kaibao tripitaka

, or Buddhist canon of the Kaibao reign (968–75), was printed at Chengdu, Sichuan, reputedly from a set of 130,000 woodblocks. It was bound in scroll form and consisted of more than 5,000 volumes, of which only a handful exist today.

The two voluminous

tripitaka

editions that were published in Fujian province in the south of China toward the end of the Northern Song (960–1127) have survived. The first was initiated at the Dongchansi Temple near Fuzhou around 1080, and the second one commenced publication at the Kaiyuansi Temple about three decades later. Each of these versions of the Buddhist canon consists of nearly 6,000 volumes in the sutra-folded binding form. They took many years to complete and obviously required a vast labor force of papermakers, block-cutters, printers, binders, scholars, and scribes.

Tripitaka

editions of equal magnitude were published in Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces and elsewhere in the north before the close of the Song period. These huge sets were intended for important Buddhist temples and other institutions. Given the nature of xylography as a sort of “printing on demand,” individual works from the vast

tripitaka

could be printed as required: thus parts of the whole came to circulate among the people.

At about the same time, in Hangzhou, a method of printing with movable type made of earthenware was invented. The Song polymath Shen Gua (1031–95) described it in a collection of essays entitled

Mengxi bitan

:

During the Qingli reign (1041–1048) there was a commoner named Bi Sheng who made moveable type [printing]. His method was to use clay to carve characters as thin as coins, each character becoming a single type, which he fired to a [certain] degree of hardness. The surface of an iron tray was then prepared with [a layer of] pine resin, wax, and paper ashes. When he wished to print something he placed an iron frame upon the iron tray, and on the tray he set the type tightly in place, filling the frame, thus making a surface for printing. By warming the tray he could soften the wax, and using a flat board he leveled the surface of the type to be as flat as a finely ground whetstone. (Zhang 1989: 664)

Obviously this new technique owed much to traditional xylographic printing (Tsien 1984). Its chief disadvantage was the enormous number of characters (written graphs) required to express the Chinese language, thereby necessitating a sizable investment in very large founts of type.

At the end of the thirteenth century in the Yuan dynasty, Wang Zhen, in his

Nongshu

(Book of Agriculture), published a detailed description of a proposed printing project using carved wooden type, but it was never realized. Despite Bi Sheng’s invention, significant typographic publications did not appear in China until the end of the fifteenth century, and the technique was used only sporadically after that. It should be remembered that the two major printing projects sponsored by the imperial court in the eighteenth century produced two founts, each of around 250,000 types, one of bronze and the other of wood.

Printing of this sort could not have been undertaken if profit were a motive, and it seems that the important and early development of commercial publishing in China influenced the dominant role of the more economically viable xylographic method of printing. According to abundant nineteenth-century data, it is clear that book production by woodblock printing in China was cheaper than any other method prior to the introduction of Western printing presses and electrotype type production in the second half of that century (Heijdra 2004a).

Xylography, of course, did not require type design in the usual sense. Nevertheless, calligraphers and copyists of texts for engraving played an important role in creating an aesthetic for the printed page. In addition to a uniform style for the main text, xylographic printing made it possible to produce prefaces in facsimile of the authors’ actual handwriting. Books containing specimens of the calligraphy of celebrities possessed commercial appeal. In fact, xylographic facsimile editions of famous texts were conveniently produced in China long before the invention of photography.