A Companion to the History of the Book (23 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

Western-style typography was introduced to Korea in 1883 by Kim Okhyun, a pioneer of Westernization who brought back from Japan a Western press and an experienced Japanese printer. Together they printed Korea’s first newspaper, the

Hanseong Sunbo

(Hanseong Ten-daily), which was printed in Chinese and appeared every ten days until late 1884. In 1885, American Methodist missionaries established a press in Seoul which printed in Korean, Chinese, and English, and it was joined in 1891 by the Anglican Mission Press. Western-style typography, however, did not replace existing technologies, even woodblock printing, until the twentieth century.

In 1910, Korea was annexed by Japan and remained a colony until 1945; during that time all publishing was under the control of the Japanese administration and prepub-lication censorship was introduced for Korean (but not Japanese) publications. At first, Korean publishing was suppressed, but after the anti-Japanese demonstrations of 1919 the rules were relaxed to allow the expression of moderate Korean nationalist sentiments, and the publication of books and newspapers in Korean flourished. Also, ways around the Japanese censors were found. As one of them complained in 1930, “The Koreans start the presses as soon as the sample copy is sent to the censor. They then keep the presses rolling until they get an order to stop” (Robinson 1984: 335).

Since 1945, publishing has followed very different trajectories in the DPRK in the north and in the ROK in the south. In the DPRK, all printed media are under the firm control of the ruling party, and it was reported as late as 1995 that “national newspapers are not sold on the streets; they are distributed to subscribers only, according to their political or professional affiliations” (Darewicz 2000: 141); however, the DPRK is in a state of flux and there has recently been some relaxation of earlier practices. In the ROK, meanwhile, freedom of expression was made a basic constitutional right in 1948, but this did not include the expression of views which contradicted the national ideals and policies of the government, one of which was anticommunism, and in practice repression was at times harsh. Consequently, in the 1970s, “the owner-publisher became the censor of his own publications” and the press “gradually became more concerned to protect its corporate interest as an enterprise than its freedom as a public trust” (Chang 1994: 258, 261). In 1987, the Basic Press Law was repealed and strict government censorship became a thing of the past.

Vietnam

Like Korea and Japan, Vietnam acquired from China not only a script but also Confucianism and Buddhism, both profoundly textual traditions. For around two millennia, an educated and bookish elite was brought up on Chinese texts. However, the melancholy fact is that, from the abortive Mongol invasion of the thirteenth century to the several wars of the twentieth century, the textual patrimony of Vietnam has suffered irreparable losses and wanton destruction. Laments for these losses have been repeated by many writers from the time of Lê Qui-Dôn (1726–84), who compiled the first bibliography of Vietnamese books.

Like Japanese and Korean, Vietnamese cannot readily be written in Chinese script, hence the invention of extra characters to facilitate writing in the vernacular. This script, a combination of Chinese characters and invented characters, is known as

nom

; it was being used by the end of the eleventh century and remained in use until the twentieth century. Meanwhile, European missionaries reached Vietnam in the seventeenth century, and in 1651 a French Jesuit published a romanization scheme for Vietnamese. The use of this script, now known as

quoc ngu

, was long confined to missionary circles, but after the southern part of Vietnam became a French colony in 1862, it was perceived as a tool to detach Vietnam from China and the Confucian tradition.

Buddhism was introduced into Vietnam in the second century. By the eleventh century it enjoyed state support, and a Vietnamese ambassador to China brought back with him a copy of the vast Buddhist canon which had been printed in China in 983. In 1031, there were nearly a thousand Buddhist temples in Vietnam, and in 1076 an imperial academy and a civil service college were established. It is evident, then, that Vietnamese must by this time have already been long acquainted both with the Buddhist textual tradition and the Chinese Confucian texts that were the cornerstone of education throughout East Asia. By this time, too, Chinese woodblock-printed books must have reached Vietnam, although when printing was first undertaken in Vietnam remains a mystery. There are persuasive accounts of a Vietnamese woodblock edition of the Buddhist canon and other works at the end of the thirteenth century, but no copies survive.

By the early fifteenth century, books had indisputably become familiar and accessible in Vietnam. Nguyen Trai (1380–1442), one of the greatest Vietnamese poets, refers often to books as a matter of course: in his Chinese poems he wrote “Beneath green trees, in silence you read books” and “Locked in your study, stay with books all day” (Huynh 1979: 73–4). Some at least of these must have been printed books, but the oldest surviving woodblock editions date from no earlier than 1697. It is from around that time, if not earlier, that printing began to add substantially to the body of texts circulated hitherto in manuscript, ranging from Chinese canonical texts and texts composed in Chinese by Vietnamese authors to Vietnamese works in

nom

. Government editions of the Chinese Confucian classics replaced Chinese imports, which were banned in 1731, and the

Dai Viet su ky toan thu

, a chronicle which covers the history of Vietnam from around 200 bc onwards, was printed in 1697. It has recently been established that some of the works written in Chinese by Vietnamese authors and printed in the eighteenth century betray the existence of earlier editions printed in Vietnam with wooden movable type, but it is not known if typography was practiced in Vietnam before the seventeenth century (Yamamoto 1999). Meanwhile, in 1668, and again in 1718 and 1760, edicts were issued banning the use of

nom

in print except for educational publications, which is a clear indication that woodblock printing in

nom

was already being practiced in the seventeenth century.

Under the Nguyen dynasty (1802–1945) Chinese continued to dominate education and learning. Scholars were repeatedly dispatched to China as envoys so that they could collect books, and in 1840 Emperor Minh-mang declared that what Vietnam needed from China was ginseng, medicines, and books (Woodside 1971: 114). Nevertheless, there was growing space for Vietnamese writing in

nom

, such as the celebrated verse novel

The Tale of Kieu

by Nguyen Du (1765–1820), and for translations of some of the Chinese classics into Vietnamese using

nom

script. The Nguyen strictly controlled printing, and most of it was undertaken in Chinese by the state or by Buddhist temples, so scribal traditions remained important for Vietnamese works in

nom

. Printing under the Nguyen continued to rely on woodblock technology, which remained the norm until the early twentieth century (

figure 8.3

).

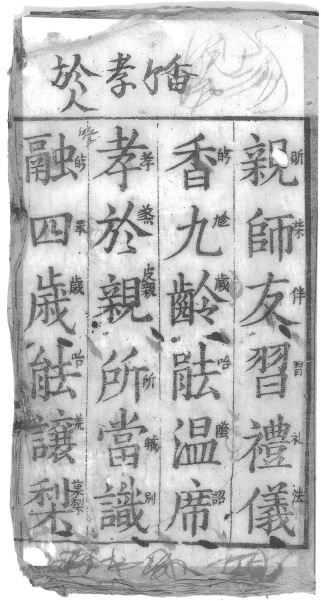

Figure 8.3

A woodblock-printed school textbook printed in Vietnam in the late nineteenth century: the large characters are Chinese and the smaller glosses are in

nom

. The textbook was amongst the items brought back by Sir James George Scott (1851–1935), who, as war correspondent of the

Standard

newspaper, accompanied the French forces conquering Tongking in 1884 to complete the French colonization of Vietnam. Reproduced by courtesy of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Under the French colonial government from 1862 onward, typography made rapid progress and was used for both French and

quoc ngu

publications. The first publication in

quoc ngu

was the first Vietnamese newspaper,

Gia-dinh báo

(Daily Paper, 1865), a government publication which also carried articles on agriculture and Vietnamese culture. Vietnamese nationalists, however, used

nom

as the language of resistance and did so until 1907, when the Tonkin Free School, founded by reformers, advocated

quoc ngu

for its educational advantages. During World War I, the colonial administration encouraged

quoc ngu

journalism for propaganda purposes, and as a result journals such as

Nam Phong

(Breeze from the South, 1917–34) appeared to appeal to the Francophile community. But as use of

quoc ngu

became more widespread, it began to serve other purposes: in the 1930s, Marxist literature was published in

quoc ngu

, as well as large quantities of anti-French pamphlets and even popular Buddhist tracts. Typography was now the dominant technology and

quoc ngu

had become the language of print, and it remained so after 1945 in both North and South Vietnam.

Since the use of

quoc ngu

for education has rendered most Vietnamese now incapable of reading earlier Vietnamese writings in Chinese or

nom

, there has been, from the late twentieth century, an increasing commitment to the publication of translations from Chinese or of transcriptions from

nom

texts to render them accessible to

quoc ngu

readers. Most of the translations and transcriptions were published between 1956 and 1975, but since 1996 there have been renewed efforts to encourage publications of this type, for considerably less than half of the premodern literary and historical texts surviving are accessible to those who can only read

quoc ngu

.

References and Further Reading

Japan

Bauermeister, Junko (1980)

Entwicklung des modernen japanischen Verlagswesens: Fallstudie Iwanami Shoten

. Bochum: Studienverlag Dr. N. Brockmeyer.

Chibbett, David (1977)

The History of Japanese Printing and Book Illustration

. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Forrer, Matthi (1979)

Eirakuya Tôshirô, Publisher at Nagoya

. Uithoorn: Gieben.

Hillier, Jack (1988)

The Art of the Japanese Book

. London: Philip Wilson.

Kornicki, Peter (1998)

The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century

. Leiden: Brill.

May, Ekkehard (1983)

Die Kommerzialisierung der japanischen Literatur in der späten Edo-Zeit

.

Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. Mitchell, Richard (1983)

Censorship in Imperial Japan

. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Unno, Kazutaka (1994) “Cartography in Japan.” In J. B. Harley and David Woodward (eds.),

The History of Cartography

, vol. 2, book 2, pp. 346–477. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Welch, Theodore F. (1976)

Toshokan: Libraries in Japanese Society

. London: Bingley.

Korea

Chang, Yunshik (1994) “From Ideology to Interest: Government and Press in South Korea, 1945–1979.” In Suh Dae-Sook (ed.),

Korean Studies: New Pacific Currents

, pp. 249–62. Honolulu: Center for Korean Studies, University of Hawaii.

Darewicz, Krzystof (2000) “North Korea: A Black Chapter.” In Louise Williams and Roland Rich (eds.),

Losing Control: Freedom of the Press in Asia

, pp. 138–46. Canberra: Asia Pacific Press.

Edgren, Sören and Rohstgrom, John (1974)

Koreanskt Boktryck 1420–1900

[Korean Printing 1420–1900]. Stockholm: Kungliga biblioteket.

Fang, Chaoying (1969)

The Asami Library: A Descriptive Catalogue

. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kim, Hyo Gun (1973)

Printing in Korea and its Impact on her Culture

. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lancaster, Lewis R., with Sung-bae Park (1979)

The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalogue

. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lee, Hee-Jae (1987)

La typographie coréenne au XVe siècle

. Paris: Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Lee, Peter (1993)

Sourcebook of Korean Civilization

, vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press.

McGovern, Melvin P. (1967) “Early Western Presses in Korea.”

Korea Journal

, July 1: 21–3.

Robinson, Michael (1984) “Colonial Publication Policy and the Korean Nationalist Movement.” In Ramon H. Myers and Mark R. Peattie (eds.),

The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1985–1945

, pp. 312–43. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sohn, Pow-key (1982)

Early Korean Typography

. Seoul: Po Chin Chai.

Vietnam

DeFrancis, John (1977)

Colonialism and Language Policy in Viet Nam

. The Hague: Mouton.

Huynh Sanh Thong (1979)

The Heritage of Vietnamese Poetry

. New Haven: Yale University Press.

McHale, Shawn F. (2003)

Print and Power: Buddhism, Confucianism and Communism in the Making of Modern Vietnam

. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Pasquel-Rageau, Christiane (1984) “L’imprimerie au Vietnam: de l’impression xylographique traditionnelle à la révolution du quoc ngu.” In Jean-Pierre Drège, Mitchiko Ishigami-Iagolnitzer, and Monique Cohen (eds.),

Le livre et l’imprimerie en Extrême-Orient et en Asie du Sud

, pp. 249–62. Bordeaux: Société des Bibliophiles de Guyenne.