A 1950s Childhood (16 page)

Authors: Paul Feeney

Some unfortunate kids had school dinners arranged for them during the holidays, which meant that whatever they were doing, they had to stop at lunchtime and go off to the school for an hour. You always felt sorry for them, because although they were on holiday, they were unable to completely forget about school, having to go in through the school gates every day and see the same old school dinner ladies. Yes, it was very sad – everyone else could put school out of their heads for six whole weeks – that is, unless

you were old enough to be at grammar school, because grammar school kids were given loads of homework to do during the school holidays. Most of them saved it all up to do near the end of the holidays, which meant that you didn’t see much of them during the final week before the schools went back.

Sometimes, one or two of the mums would round up the neighbouring kids and take them off to the country or seaside for a day trip. It wasn’t a task to be repeated more than once in any one summer holiday period; those mums needed the patience of a saint, as well as a firm hand – and a well-earned lie down when they got home. Perhaps these familiar words still echo in your ears: ‘Never again!’

Much time during the school holidays was well spent and industrious; it wasn’t all playtime. You spent a lot of time making things, mainly out of old bits of wood, like go-karts made out of old crates and prams, and sledges with removable ball-bearing wheels, which allowed them to be used in the concrete streets of summer, and on the snowy hills come wintertime. Then there was pocket money to be made out of collecting old newspapers, bottles and metals, and taking them down to the scrapyard for recycling. Towards the end of the summer holidays, thoughts would include plans for the next big event of the year, Bonfire Night. Gathering wood, logs and old bits of furniture while they were still dry, and storing them in some sheltered place, ready to be retrieved nearer the day itself in November. You needed a lot of stuff to build a huge bonfire, and it had to be collected over a period of time and be as dry as possible, so that it would blaze rather than just make smoke.

As August drew to an end, your mind was forced to start thinking about school again. Your mum would drag you out shopping for a new school blazer and some lovely new ‘fish-box’ shoes for you to wear for the new autumn term. You had mixed emotions about going back to school. On the one hand you wanted to see all the mates that you hadn’t seen during the school break, but on the other hand you were nervous about going back to an unfamiliar new classroom and possibly new teachers. You also didn’t want the summer to end, or to even think about the approaching dark evenings of autumn. The real anxiety came when you were eleven years old, and the time had arrived for you to start at a new secondary or grammar school – really nerve-wracking!

Christmas is always the most special time of year for children, and so it was in the 1950s. The festive season was much less commercialised than it is now, but then there was no Internet or telephone selling, and modern terms like ‘marketing’ and ‘direct sales’ weren’t even in common use. Goods were mostly sold in shops, and sometimes through newspaper adverts or by door-to-door salesmen. We all believed in Father Christmas, and of course we still do! At Christmastime, young children would be taken to see Father Christmas in his grotto at the nearest department store. You would be encouraged to sit on his knee and tell him what you wanted for Christmas – nothing too big of course! This strange tradition contradicted everything you were taught about being wary of strangers – taking you into a small, scary, cave-like place and urging you to sit on the knee of a strange man who is dressed from head-to-toe in a bizarre disguise. It’s no wonder that lots of terrified young children kicked and screamed their way out of the place!

Having already endured the post-war austerity years of the late 1940s and early ’50s, many people were still struggling to make ends meet in the mid to late 1950s. Even the better-off families spent their money sparingly, if only out of habit, and it was just the lucky few that could expect to receive big expensive presents on Christmas morning. In schools, children were taught to focus on the true meaning of Christmas, and were encouraged to make the most of the events surrounding the whole of the Christmas period rather than just the presents they might get on Christmas morning.

Remember those wads of assorted coloured paper strips that you made paper chains with at primary school? Everyone in the class was given a bundle of them and put to work to make their own section of the chain, rolling each strip into a circle and fastening the ends with glue to form additional links. Gradually the paper chain grew in length until the combined sections were deemed to be long enough to link together and decorate the classroom walls. You will also have made other Christmas decorations to hang from the ceiling and fill in empty spaces on the walls, probably using crêpe paper. And best of all, you will have made Christmas cards and Advent calendars that you sprinkled with colour glitter, which got everywhere, even in your hair and up your nose. It was all cheap and cheerful, but the whole preparation process for Christmas was so exciting, at school and at home.

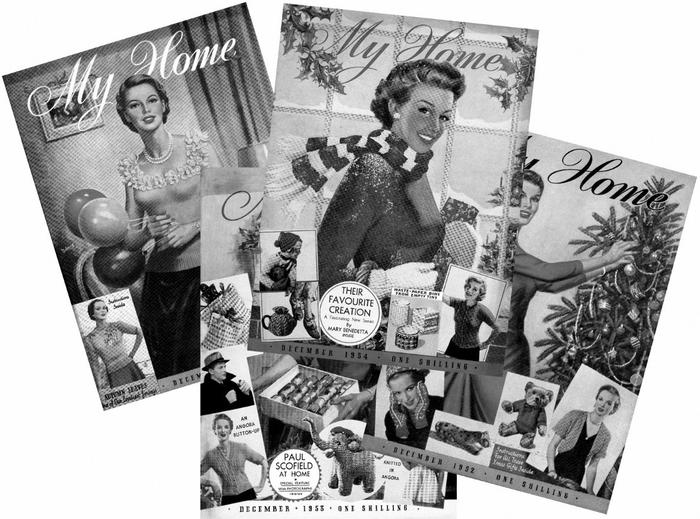

Magazines kept the family informed as to what a home should look like at Christmas.

It seemed an age since the autumn half-term holiday, which was back in October, and it was over a month since the excitement of Guy Fawkes Night. There wasn’t much to break the monotony in between the summer holidays

and Christmas, and what with the dark nights of autumn being so cold and damp you just longed for Christmas to arrive and cheer everyone up! Unlike today, the Christmas season didn’t really begin until well into December. It would be early in December before you would see the first real signs of Christmas on the high street, with shops decorating their windows to look festive. At about the same time, your school would start to plan for its customary Nativity play, and they would begin to organise choir practice for the Christmas carol concert. Once the school’s Christmas activities got under way then the whole

atmosphere around school was very different from the rest of the year. Even if you weren’t chosen to play the back half of a donkey in the Christmas Nativity play, you could still help to make the costumes and the scenery for it. And, so what if you were only going to be second reserve for playing the triangle in the school band on the big day, you could still enjoy the rehearsals! Being chosen to help make the traditional classroom crib for baby Jesus was a big honour, and there were many disappointed volunteers, but learning to sing all those Christmas carols really did lift everyone’s spirits. It was your first experience of do-it-yourself, fabricating an old cardboard box into a credible animal stable using very little in the way of materials; paint for the walls, cotton wool to represent snow on the roof, and straw to cover the floor of the stable – not forgetting a big shiny star made out of cardboard and covered in silver glitter. Once the stable was finished, you had to position all of the handmade Nativity crib figures inside: baby Jesus in a small straw-filled manger, Mary and Joseph, the three kings bearing gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh, and the donkey – with as many other animals as you could fit in. There were always some funny looking camels – or perhaps they were sheep! It didn’t matter if you came from a religious background or not, everyone got into the theatrical mood of Christmastime. Schoolwork was much less tedious during those few weeks in December because you were so immersed in the excitement and celebration of Christmas, and lessons were just something that happened in between. Your main thoughts didn’t revolve around what you would be getting for Christmas, or how big your presents would be. You were caught up in the

whole occasion of the season, and it was the combination of events that made it all so enjoyable. Usually, in primary school, shortly before you broke up for the Christmas holidays, you had your school Christmas party. If it was a big school then you probably had a party just for your class, with loads of jelly and fairy cakes, Christmas music, and games like pass the parcel and musical chairs. Christmas really was worth waiting all year for!

These were times when women were not yet fully emancipated; there had been a lull of more than twenty years in feminist activities, and women’s equality issues didn’t spark off again until the 1960s when the second-wave feminist activists rose from behind the parapet to re-ignite the arguments for women’s cultural and political equality. Working women of the 1950s were not paid the same rates as men, and men were considered to be the breadwinners in the family while women were thought of as homemakers, and whether they held down a full-time job or not, women were expected to look after the home and care for the children. They just couldn’t shrug off the ‘housewife’ tag. The age of ‘modern man’ had not yet arrived, and 1950s men just didn’t do washing, ironing or shopping. As a result, the task of Christmas shopping was left mainly to the woman of the house – your mum.

At Christmastime, more so than usual, you were probably enlisted as a reluctant bag carrier, following in your mum’s footsteps as she trudged around every market stall, shop

and department store on the high street, shopping for all those Christmas essentials. There were no shopping malls, supermarkets or self-service shops to brighten the shopping experience. Instead, there were loads of individual specialist shops, and shopping seemed to take ages, what with your mum stopping for endless chats about the weather with each shopkeeper, and dread the thought of her meeting a friend en route – that could take up an hour! Constantly weaving in and out of shops and between market stalls, the bags gradually got heavier and heavier, and if it was raining, you just got wet!

At Christmas, the high street atmosphere was so different to today. You didn’t see people walking around with silly red Santa Claus hats and brightly coloured Bermuda shorts like you do now. People were much more reserved back then, and even got dressed up in a posh frock or a shirt and tie to go high street shopping. The shop window displays were always very Christmassy, particularly in the department stores, where windows were dressed with all sorts of wonderful festive scenes. Many a lost child would be found gazing through a department store’s window at a display of lifelike mannequins and wondrous objects that had been arranged into a Christmas setting; he or she would be completely captivated by a scene that was worlds apart from their own lifestyle. The air around the street markets was filled with the smell of fresh pine Christmas trees, and the market stalls were strung with hundreds of coloured festoon lights. There was always a man on the corner roasting chestnuts over red-hot coals in a brazier – another great smell of Christmas! The Salvation Army band played festive music and sang carols, generating goodwill

and encouraging everyone to drop a few coppers into the hat for charity.

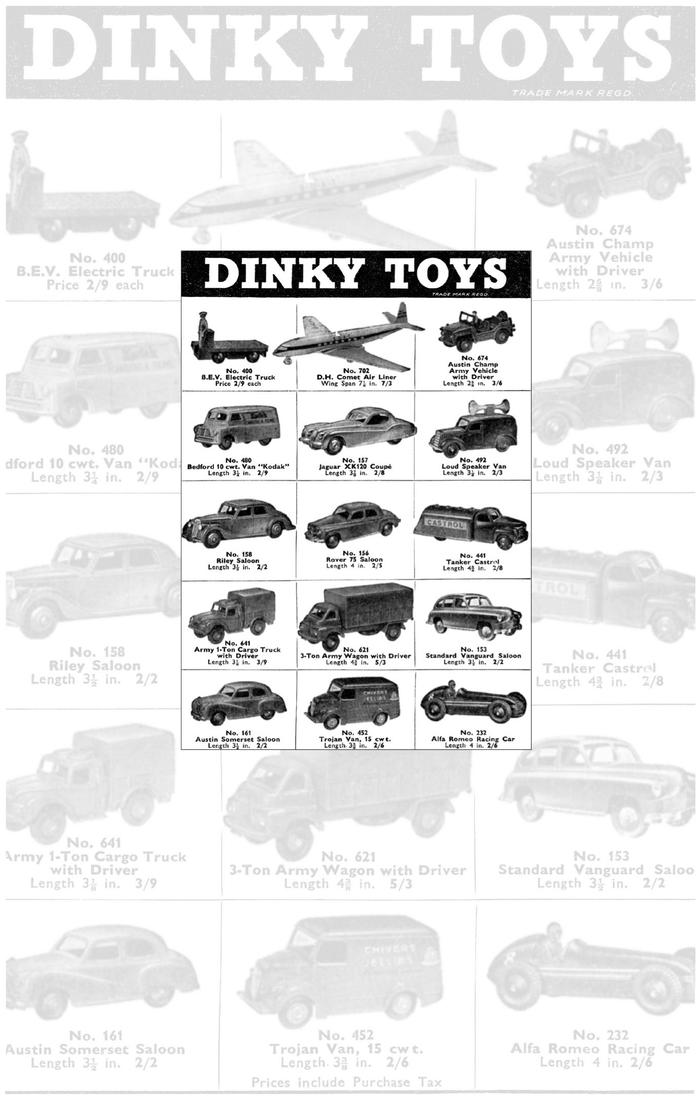

In your eyes as a young child, Christmas shopping didn’t include buying toys or presents for you or your siblings because Santa brought your presents on Christmas morning. Presents were bought for family and other people, but they always seemed to be boring presents, like scarves or socks – nothing exciting like a Davy Crockett hat or a high-speed glowing yo-yo. Even with all those marvellous toys, games and novelties on display in shop windows everywhere, your mum’s main focus was on food. By the late 1950s, still only one in four families in Britain had a fridge, which meant that most working-class families managed to live without a fridge throughout the ’50s. Mums needed to do a lot of strategic planning when buying food, drink and other perishables, particularly when there was the added burden of rationing in the early ’50s. Food wasn’t pre-packed in plastic as it is today, and nothing was date-stamped with use-by dates. You had to buy things as fresh as possible to get maximum use out of them, but there was no way of telling how long something had been in the shop, let alone how long it had been in the food processing chain. Mums acquired the skill of detecting the freshness of things like meat, fruit and dairy products; but however fresh the food was, without the use of a fridge your mum had to shop every couple of days to keep the family fed and avoid food going off. Unlike today, you couldn’t just pop out to the shop at any time of the day or evening, seven days a week. In the 1950s, many shops were shut on Saturday afternoons, even large stores like John Lewis in London’s Oxford Street. And, apart from the

corner newsagent’s shop that opened for a few hours on a Sunday morning, there were no shops whatsoever open on Sundays. On top of that, every area had its half-day closing each week, usually on a Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday. Some shops didn’t open at all on Mondays; again, John Lewis branches used to be closed on a Monday to give staff, known as Partners, a proper weekend break.

You really needed to know your local shopping area’s opening and closing times, and plan your shopping needs around them. This was even more difficult at holiday times like Easter and Christmas, when all shops were shut during the bank (public) holidays. If Christmas Day happened to fall on a Monday then the last day for buying food was Saturday, and it would have to last until the following Wednesday when the shops opened for business again. Even on the Wednesday, other than on-site family bakers, most shops wouldn’t have any fresh food stocks because nobody had been working over the Christmas period to produce them. Therefore, mums tried to buy enough food to last through until a couple of days after Christmas. This led to large pre-Christmas queues outside shops selling bread, vegetables and meat. Most mums placed advance orders with the shopkeepers but they still had to queue to collect their order. It wasn’t unusual to see enormous queues gathering outside baker’s shops on the day before and the day after a holiday. Bread was a very important part of a child’s diet, often the cheapest and quickest remedy for your hunger pangs, and families didn’t like to run out of it. Tinned meat and other tinned foods were also bought as a back-up. Then there were all the Christmas trimmings, like nuts and dates, Christmas crackers and balloons, and

perhaps a few replacement decorations for the ones that were broken last year. Your dad was roped in to get the Christmas tree and to make sure there was enough coal or logs for the fire, and while he was at it he probably bought a few bottles of something ‘special’ to add some Christmas cheer. Even people that didn’t usually keep any alcohol in the house would make sure they had a bottle of Sherry and a bottle of Port to offer visitors a Yuletide drink.

The tradition of sending Christmas cards is still very strong today, but in the 1950s few homes had telephones installed and so the only way to pass on Christmas greetings to family and friends was by way of Christmas cards, postcards or letters. This was another task usually left to mum – not much has changed in that regard! The build-up to Christmas started much later in the home than at school. There may have been some early recognition of it approaching; perhaps your dad had a go at making a doll’s house, or your mum might have started knitting a ‘lovely’ Christmas jumper for some lucky recipient. Mostly, there was little evidence of Christmas until very near the day itself, when the decorations went up in the living room and a space was made for the tree. You probably also cleared a spot on the sideboard where the crib could go, and helped mum and dad to blow up the balloons – an impossible task for young lungs with little puff.