A 1950s Childhood (13 page)

Authors: Paul Feeney

Whack-O!

(1956–60) BBC TV. British comedy sitcom series, written by Frank Muir and Denis Norden, and starring Jimmy Edwards as Professor James Edwards MA,

a scheming, gambling, drunken, cane-wielding headmaster of fictional Chiselbury public school. The show also starred Arthur Howard, who played Professor Edwards’ long-suffering assistant, Mr Oliver Pettigrew. You may remember Professor Edwards’ favourite saying, ‘Bend over, Wendover!’

The Woodentops

(1955–7) BBC TV. Part of the

Watch With

Mother

series, written by Maria Bird. It was about a family of wooden dolls who lived on a farm. The main characters were Mummy Woodentop, Daddy Woodentop, Jenny, Willy

and Baby Woodentop. The series was devised to introduce children to the ways of the country.

Zoo Time

(1956–68) ITV. Featured Desmond Morris, with the help of various animal experts and zoo staff from Regents Park Zoo in London. It offered lots of information about animals, using pictures taken from around the zoo. The early shows always featured Congo the chimpanzee.

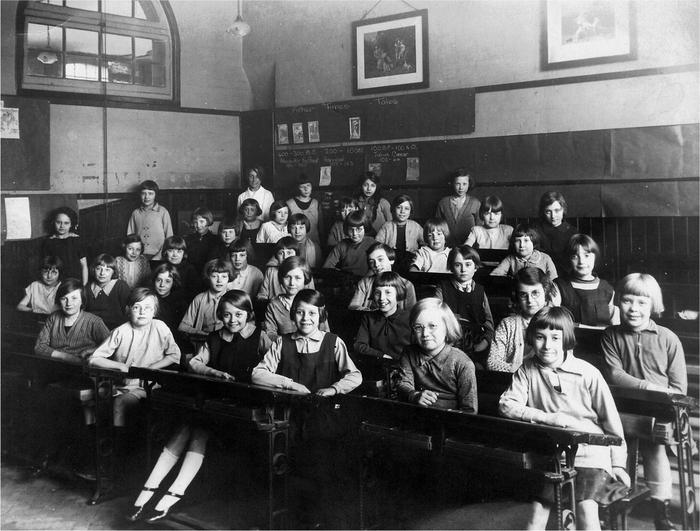

Your first day at school; it was the loneliest day of your young life. You were just four years old when your mum took you into the school, kissed you on the cheek, then turned and walked away, leaving you alone and abandoned. There were no working-class nursery schools, kindergartens or playschools to prepare you for the distress you felt that day. Up until that moment, you had always followed in your mum’s shadow. You had never before been left alone with strangers and you are suddenly forced to realise that your mum had always done everything for you. For the first time in your life, adults that you don’t even know are asking you questions and telling you to do things, and your mum isn’t there to deal with it for you. You are in strange surroundings that are filled with odd smells, and there are unfamiliar things all around you, with lots of kids that you have never seen before. Your mum had taught you to be well-behaved but you weren’t prepared for the discipline of school life. The teacher shows you to your seat and tells you to sit still

and be quiet. This is not going to be any fun at all – and where are all the toys?

Many schools had a school uniform policy, which was designed to be affordable and could also be worn outside school. Girls’ uniforms were often just a white blouse, grey gymslip or pinafore dress, white socks and navy blue knickers – girls never wore trousers to school. Boys would wear a white or grey shirt and short grey flannel trousers with itchy long grey ribbed woollen socks – with at least one uncomfortable darned toe. There was frequently a school tie and some schools also had very tasteful headgear as part of the uniform. Both boys and girls would wear a blazer that often doubled as a best jacket for the boys to wear on Sundays. School shoes were generally heavy black round-toed monstrosities that were nicknamed ‘fish-boxes’, and there were black plimsolls for games and PE (physical education). As a rule, it was a bit uncool for boys to wear raincoats or overcoats, but girls regularly wore them. These coats were always bought two sizes too big to allow for growth and to give at least a couple of years’ wear; and because they were indistinguishable they all had the owner’s name neatly sewn into the collar.

If you lived in a rural area, you may have travelled by school bus or train, but most 1950s kids walked to school and some lucky ones cycled, sometimes quite long distances. Very young children were escorted to school by one of their parents, but once they knew how to get there then most children made their own way to school, particularly if they had older siblings or friends to accompany them. The streets were safer then, and you never heard of children being abducted. Walking to and from school could in itself

be an adventure; running alongside cars and trying to keep up with them, hopping from flagstone to flagstone while avoiding every crack, running along the tops of walls, climbing trees, and the annual ritual of collecting conkers that fell from the horse-chestnut trees every autumn.

You had to pay to go by bus unless you lived a qualifying distance from the school, whereby you got a bus pass. In the towns and cities, with car ownership still relatively low, trolleybuses were the main means of transport to school for children that lived too far away to walk. Travelling by bus was quite different then; everyone queued in an orderly line at the bus stop and there was no pushing or shoving to get to the front. If there was a bend in the road, or a hill that was obscuring your view of oncoming traffic, then you could tell when a trolleybus was approaching by looking at the movement of the overhead wires, to which the springloaded trolley-poles on top of the buses were connected. Or, you could put your ear against the post at the bus stop and listen to the increasing vibrations. Experience taught you just how far away the bus was depending upon how much the wires were moving. You would always go upstairs on the bus for a better view, and it was even better if you could get a seat at the front, but it was always very smoky because people were only allowed to smoke upstairs on the buses.

‘Hold very tight please’, ding-ding. There was a uniformed conductor on every bus whose job it was to collect fares and to make sure everyone got on and off the bus safely. There was no passenger door on buses, just an opening at the back with an upright centre pole for you to cling to as you got on and off. The conductor carried a long

narrow wad of different-priced tickets, from which he or she would pull a ticket and clip it before handing it to you. They would always take your money, count it and then put it in their leather moneybag before handing you the ticket. Sometimes the conductor would take your money just as the bus was arriving at a bus stop, which meant that they had to go to the back of the bus to supervise passengers getting on and off the bus – it seemed they would always forget to come back with your ticket!

In the 1950s, even the infant school had strict discipline. The classroom was geared to learning, not playing. There was no sign of a cuddly toy or hint of an afternoon nap. The teachers did adopt a more gentle touch for the infants, but talking in class, fidgeting or not paying attention would lead to a slap across the legs and being made to stand in the corner of the classroom facing the wall. Punishment would undoubtedly upset you, but there was also a new feeling that you had never felt before – you had been shown up in front of the other kids. That ‘new feeling’ was humiliation. Once you got used to the discipline of being at infant school, you found that there were lots of fun things to do, and the teachers actually made learning enjoyable!

The school day was normally seven hours long, including lunch and break times. The starting and finishing times varied from school to school, with starting times from 8.40–9.10 am and finishing times from 3.40–4.10 pm. Most schools had morning assembly, which more often than not included prayers, and then you went off to your classroom for the register to be checked.

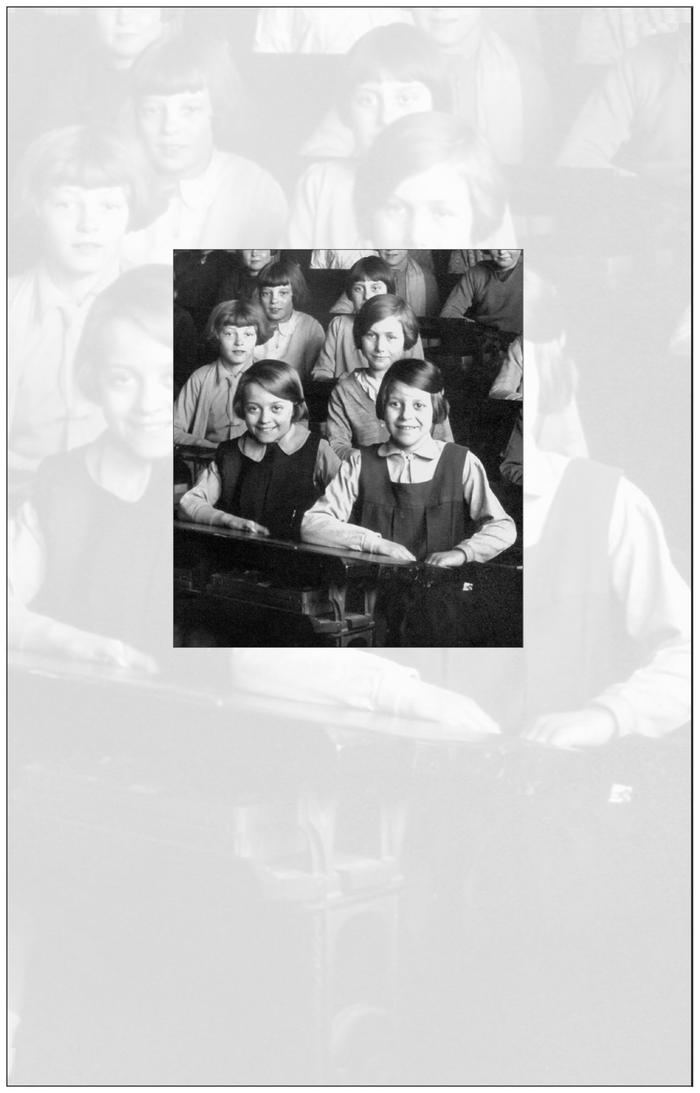

A classroom full of young schoolgirls sitting at typical 1950s metal-framed desks with sloped desktops that are fitted with inkwells.

You usually transferred into the junior or primary school proper between the ages of five and six, by which time you

knew your alphabet and could do basic arithmetic with the aid of an abacus. You gradually progressed from writing with chalk on a small blackboard to using pencils, and when you had mastered the use of a pencil you were taught to write with pen and ink. This involved using a crude wooden stick with a metal nib fixed to one end, which you dipped into an inkwell at the top of your desk to load the nib with enough ink to write a couple of words at a time.

It was really messy! There would be ink everywhere, with splodges all over the pages in your exercise book and on your hands. Loading just the right amount of ink onto the nib was the key, and it helped if you had an undamaged nib to start with.

Class sizes varied considerably depending on where you lived. People often had large families and in the built-up areas it was quite normal to have more than forty children to a class. Sometimes a classroom could not accommodate enough desks, which meant that some had to share. If seated at the back of a large class, a quiet or shy child with poor eyesight or hearing could go unnoticed by the teacher and struggle to keep up with lessons – sometimes harshly branded as being lazy! Teachers back then probably weren’t trained to identify such problems, and some were less than sympathetic with children that didn’t conform to what was seen as the norm, as with their criticism of left-handed kids who were often encouraged or even forced to write with their right hand, sometimes earning a slap on the back of the hand if they were seen writing left-handed.

Some schools had a daily ritual of dishing out cod liver oil to all youngsters, but in other schools cod liver oil was only given to certain unlucky individuals; this was never really explained but it did seem to be linked to sickly looking kids and those on free school meals. Similarly, some kids had their hair more regularly checked for nits than others. Yes, alas, we all had regular inspections by the ‘nit nurse’! There were also regular school medical inspections, when a doctor would visit the school and you would all line up to be examined. It was usually a male doctor and he would pull you about, checking you all over, then weigh

you, measure your height, and make you do things like pick up a pencil using your toes. Everyone hated the ‘nit nurse’ and doctor inspections.

Apart from having fun, your main ambition at primary school was to be made a ‘monitor’. Any kind of monitor would do. You will remember everyone putting their hands up in class to volunteer when there were pencils or paintbrushes to be given out, and the collective call of ‘Me Miss! – Me Miss!’ As well as giving out the pencils, the pencil monitor got to use the huge pencil sharpener that was mounted on the edge of teacher’s desk at the front of the class – how exciting! It was recognition of your trustworthiness and you felt quite important to be given the responsibility of teacher’s little helper. Milk monitor was a rotten job; you didn’t put your hand up twice to be the milk monitor. Remember those small bottles (one-third of a pint) of free school milk you had each morning throughout your school life? Nice and refreshing in summer, but very cold in winter. The milk monitor had to handle all those freezing cold milk bottles and the metal crates they came in. The job of class monitor was best suited to girls because it involved having to ‘tell’ on your classmates if they misbehaved when teacher was out of the classroom. Not that girls were better at telling tales, it’s just that boys didn’t usually last long in the job; they would at best be ostracised by their mates in the playground if they got someone in trouble with the teacher.

There were lots of fun things to do in class, like drawing, painting, and making things with plasticine and other materials. Everything you did would be given a mark out of ten, and little stick-on coloured, silver and gold stars would

be awarded for good work. You were also taught the basics in science and nature, but the majority of class time was spent on learning ‘the three Rs’, a long-established phrase that was used to describe the basic skills of reading, writing and arithmetic. You were never in any doubt that school was a place for learning.

There were very few male primary school teachers around at the time. The teachers were mainly women and most appeared to be very old, but then again, to a child anyone over the age of twenty-one looked old, and I suppose they did in the 1950s. On the other hand, every primary school did seem to have just one nice-looking young schoolteacher that everyone wanted to have as their class teacher. Children would describe their teacher as nice, horrible, or all right, without realising the true value of that teacher, good or bad, until later in their young lives. As in every generation, the 1950s primary school teachers had varying levels of knowledge and teaching skills. Some were lazy and boring, limiting themselves to teaching the basic three Rs, whereas others were true vocational teachers that involved themselves in every aspect of teaching; attending after-school courses to learn additional things like drama, painting, handicrafts and music. If you were lucky enough to have had one of those enterprising primary school teachers then you will appreciate the contribution that he or she made to your development. They made schoolwork enjoyable for their pupils and provided a complete mix of education. It was usually the same resourceful teachers that took you for swimming lessons at the local baths, arranged needlework and dance classes for the girls, and taught the boys how to play football and cricket properly. He or she

would have been there when you were given your first tambourine or triangle to hit as part of the enthusiastic but shambolic school orchestra; and who was it that taught you how to breathe when you practised for the school choir’s Christmas carol concert? On cold winter days, your teacher sat at the front of the class and bewitched you with readings from children’s fictional story books, or fascinated you with tales of British history; the ancient Egyptian mummies, The Battle of Hastings in 1066, King John and The Magna Carta of 1215. It made you feel warm inside, and even though playtime was fast approaching you didn’t want the story to end.