A 1950s Childhood (15 page)

Authors: Paul Feeney

At school, you did loads of physical education and sport, with hard-working PE sessions two or three days a week, and typically there would be a weekly games afternoon for competitive sports like football, rugby, cricket, rounders,

tennis, hockey, netball, and not forgetting athletics. There was also extra training after school, and school league competitions were held on Saturdays. Just to be sure that you used up every spare ounce of energy, some schools even taught and competed in additional sports like boxing, judo and weightlifting.

Everything was so different at secondary school; what with your new friends and a much heavier workload, you just didn’t have time to look back at your primary school days. You were gradually leaving your childhood behind and moving ever closer to becoming a moody teenager.

Corporal or physical punishment, the act of inflicting pain by means of beating or caning, was legal and widely practised in Britain’s schools during the 1950s. At the time, the psychological effects of physical punishment on children was not considered as adding to the punishment, but anyone who experienced corporal punishment in school will know that the suffering was not limited to the pain felt at the moment of impact. You would often know in advance that you were to be caned, and this would cause a build-up of mental anguish that would today be regarded as cruel. Being punished in front of the class or school would be humiliating and add significantly to your mental suffering. Then there was the after effect, with the extra stress of hiding it from your parents – the unwritten law of the playground was ‘not to tell tales out of school’; and of course you didn’t want them to find out anyway or you

might get another wallop for having misbehaved at school in the first place. The actual pain of the cane or tawse could last for several hours, with welts and bruises remaining evident for days.

In primary schools, physical punishment was mostly limited to a slap using the palm of the hand across the back of your legs, arms, or hands, and sometimes the back of the head. A wooden ruler was also used to administer a rap across the knuckles, hands, or back of the legs. The cane, slipper, or tawse (in Scotland) was usually reserved for older primary school boys. There was no negotiation or appeals; if in doubt give the child a clout!

Corporal punishment was much more prevalent in secondary schools, but again, predominantly for boys, although you did hear stories of girls being slapped with a slipper or caned. Boys’ schools sometimes had designated ‘punishment rooms’, with specially appointed ‘punishment teachers’ to do the wicked deed. There is no doubt that the use of corporal punishment in schools was practised with great enthusiasm by some cruel and cowardly teachers who took pleasure in beating even the frailest of young boys. Although schools were supposed to keep records of any corporal punishment they dished out, in what were called ‘punishment books’, the rule was not adhered to and punishment would often be meted out on the spur of the moment, and sometimes at random with the teacher not even knowing who was being beaten, or losing count of the number of strokes being landed on the target. Clouts across the back of the head for not paying attention were commonplace, and there was an unending supply of chalk, blackboard dusters and other missiles thrown

across the classroom as instant recognition of someone’s misbehaviour.

All forms of discipline were seen as a natural part of the education process, and physical punishment was even considered to be ‘character building’!

Every day off school was greatly valued, as it seemed that you spent an awful lot of your time there. Apart from the traditional six weeks summer holiday, other school breaks were short and scarce. There were no special days off, as with the ‘occasional days’, ‘teacher training days’, and ‘non-pupil days’ of today. Half-term breaks were often limited to two days, with Easter and Christmas extended to one full week, and that included the official public holidays. If you went sick during term time then you might get a visit from the school board man to check up on you (most people didn’t have telephones back then). Truancy was frowned upon and strictly dealt with – there were what was called ‘school board men’ that would lurk around neighbourhoods to catch kids bunking off school. If you were caught then you would be dragged back to school for punishment, and your parents would get a visit and a lecture from the school board man, threatening all sorts of things, including the possibility of you being sent to borstal if you were caught again. There

were different expressions used to describe skipping-off school depending on what part of the country you lived in. These included ‘hopping the wag’, ‘wagging it’, ‘playing the wag’ and ‘skiving off’. Of course, it was only the very bad kids that did it!

Most working adults only got two weeks paid holiday a year, with part-timers and piece-workers getting no holiday pay at all. They often had to take their holiday at a time determined by their employer, such as during factory closedown periods. This was usually in the main summer months, and so families that could afford it would try to get away for a few days during the school summer break. It was only the well-off that went away on holidays at other times of the year.

Cheap European package holidays and affordable long haul flights to exotic places didn’t exist in the ’50s, and the thought of spending a fortnight’s holiday on a sun-soaked Greek island was way beyond your wildest dreams. Here in Britain, the ‘Hi-di-Hi!’ style holiday camps at popular seaside resorts were all heaving with fun-loving, knobbly knee contestants, and game-playing holidaymakers. All the caravan sites, seaside chalets and beach huts were also full to the brim, as were the traditional seaside boarding houses. Not everyone could afford to go away on holiday. It was in the days before credit cards arrived in Britain, so people had to have the cash available to pay for a holiday, otherwise they just couldn’t go. Many working-class families strived to

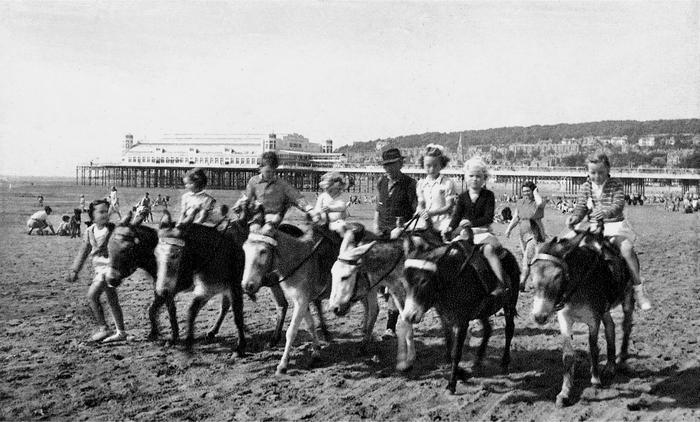

save enough money to have a modest seaside holiday, and to get some healthy sea air into their kids’ lungs. If you were lucky enough to go on holiday, then it was likely to consist of a week at one of the popular seaside towns around the country, with sticks of rock, ‘naughty’ postcards, donkey rides, and ‘kiss me quick’ hats.

A group of children wearing sagging, wet bathing suits play in the shallow water on a Fife beach in 1951.

In 1950, buses and bicycles were the most popular modes of transport. At the time, there were just under 2 million cars registered in Britain, with only 14 per cent of households owning a car (by 1998, it was 70 per cent). In summer, many families did load their luggage into the boot

of a classic motor car of the day, like the Ford Prefect 100E Deluxe or the Austin A35 Saloon, but most families headed off to the nearest railway station to catch a train that took them right to the doorstep of their holiday destination. It was in the days before the Beeching ‘Axe’ Report (1963), which accelerated the mass closure of railway branch lines all across the country, at a time when you could still access small holiday resorts by train. The train journey created an atmosphere of excitement, as you trundled past the advertising hoardings and the grimy soot-stained walls that encased the railway station, out through the built-up areas and into the beautiful countryside. The panoramic view from the train revealed a countryside scene that was so different, and really eye-catching. You were mesmerised by the ever-changing landscape combined with the rhythmic motion of the train. You passed through all sorts of tiny village railway stations, deep into unfamiliar rural areas, way beyond the safety of your home turf. As captivated as you were by the moving scenery, you eventually got fed up fiddling with the adjustable leather window strap and began to ask the inevitable question – ‘When will we be there?’

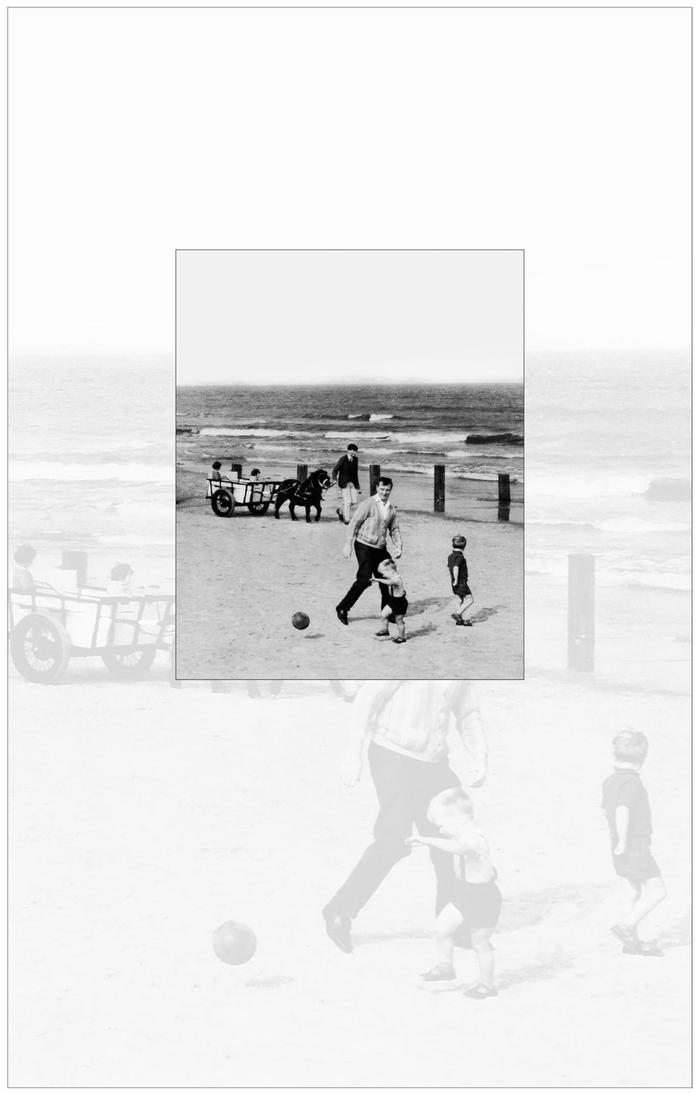

The beach huts, boarding houses and caravan sites were boring places for children, but kids of the ’50s were used to finding things to occupy their time, and would do what they did at home – make up games, but on the beach rather than in the streets. Parents weren’t into finding things to entertain the kids. After all, they had gone away for a rest as well, and there were no deep pockets full of cash with which to wander endlessly around amusement arcades, feeding the slot machines.

Casual wear was not something that grown-ups did very well in the 1950s. Men wore their everyday jacket and trousers to the beach, complete with shirt, tie, socks and shoes. They might stretch to a pair of brown sandals, but they would always be worn with socks! Your dad was really ‘cool’ if he wore a cotton t-shirt, or a patterned short-sleeve shirt. Once on the beach, he would take off his jacket and roll up his shirtsleeves, just to give the appearance of being laid-back. After fighting for several minutes to get the folding deckchair to open, he would settle down into it and don his knotted white hankie to protect his head from the sun. Some time later, he might take off his shoes and socks, roll up his trousers, and venture down the beach to dip a toe into the cold seawater that was lapping the shoreline. Brave dads even changed into swimming trunks and shivered their way down into the sea for a swim. Women commonly wore their best flowery summer dress to the beach, and maybe some white sandals for comfort, but it was not unusual to see women stumbling across the beach in three-inch high-heel shoes. There were a wide variety of swimsuit colours and styles for women, but although the daring two-piece bikini had been around for some time, there wasn’t much evidence of it on Britain’s beaches. Bikinis were mostly worn by beautiful Hollywood stars and jet-setters on beaches in the South of France. In Britain, we were a bit slow on the uptake. Perhaps it was our weather that made the ladies favour a one-piece, zip-up, corset-style swimsuit, with the essential modesty apron across the top of the legs to hide the swimsuit’s crotch area. They were made in various fabrics and looked great until they got wet, retaining the

water and forming into a much less attractive shape. With all their fashionably permed hair and bouffants, women liked to protect their hair from getting wet in the water, and so they donned colourful rubber bathing caps that were lavishly decorated with designs of flowers, petals and shell-like shapes. Young girls commonly wore seersucker swimsuits, and even woollen knitted swimsuits that sagged down to the knees when they got wet.

A group of children enjoy a donkey ride on the beach at Weston-super-Mare in the summer of 1955.

A few days later, with all of the penny arcades, Punch and Judy shows, paddling pools and funfair rides done; and stuffed full of candy floss, whelks, fish and chips, and jellied eels, it’s time to pack up and head for home to see your

friends and enjoy the rest of the school holidays. One last peek at the saucy picture postcards outside the shops along the seafront, and you’re off.

The summer holidays were so much more enjoyable than short half-term breaks. You had much more time for playing outside, getting up to mischief and making new friends. You had the good weather and light evenings, which meant more time for street games, and you were able to take whole days out to do things that you usually couldn’t do, like go fishing, go to a roller-skating or ice-skating rink, or swimming at the nearest lido. If you had enough money, you might even go to a fairground or some other summer event, like a county cricket match. There were loads of things to do, and if you were broke you could still go to the park with your mates to kick a ball around, climb trees, or sail your homemade toy wooden boat on the lake. When you tired of playing, you could lie down in the fields to soak up the sun and make daisy chains.

Holiday or not, there was no rest for the wicked – your mum still got you out of bed at the crack of dawn, which meant you had long days to fill. There was a lot of unsupervised playtime during the holidays because dads were out at work all day, and a lot of mums also went out to work, either full-or part-time. Even mums that didn’t go out to work seemed always to be busy indoors, with endless washing, ironing, cooking and cleaning. There were very few labour-saving devices in the average home, and most of

these household jobs were done manually, which was really hard work.

It was a safer and more trusting time, when children were allowed to play out in the streets and around the neighbourhood without parents getting unduly worried. As long as you were out in a group, then you did things together and looked after each other.

Some of your most memorable summer days were spent out in the open, playing doorstep games in the sunshine. Games like Monopoly went on for hours and gave you a lot of enjoyment; it was educational in many ways, not least because it taught you how to add up. Card games were regularly played outside, on someone’s doorstep or on a patch of grass, sometimes just for fun but often for a stake – rarely money, more often for matchsticks or something that was tradeable, like cigarette cards or marbles. Most kids knew how to play lots of card games, usually having learnt them from friends and relatives on dark winter evenings around the dining table, before television became the main form of entertainment in the home.

There weren’t many cars or other motor vehicles around in the ’50s, and a lot of back-streets were completely free of them, making them ideal playgrounds. A few lucky kids had bicycles, and long streets and alleyways were perfect for bicycle races, where boys and girls would take turns in racing the bikes against each other. Sometimes the races got dangerous, like when you competed to see how many you could fit on a bike at one time, and still ride it. Five was about the limit – saddle, crossbar, handlebar, and front and back mudguards. These antics often resulted in some bumps and scrapes, and the kids sometimes got hurt as well!

During the holidays you took each day as it came, knowing that tomorrow was another holiday, and the day after was another, and so on. Very little was planned in advance. You didn’t listen to, or worry about the weather forecast. If it rained, then you tried to play somewhere under cover. Boys might retreat to a mate’s house to construct some Meccano, or play Subbuteo, while girls were content to play dress-up with their mum’s clothes and make-up, indoors. If you were stuck for something to do, then you went up to the high street to check out what was new in Woolworths. They always had something that you hadn’t seen before, like the latest in wind-up toy cars. The girls spent ages looking through the range of cheap costume jewellery – a beaded necklace was only 1s 3d (one shilling and threepence). Woolworths had things that you didn’t see anywhere else. At the time, it was the only place where you could buy Rupert the Bear Annuals. The pick ‘n’ mix counter was one of the biggest temptations, and best avoided. If you were spotted hanging around the sweet counter, you got chucked out. They knew you were just sheltering from the rain and weren’t in there to buy anything.