1968 (65 page)

However, on December 16 the Spanish government tried to show its concern for justice by voiding the 476-year-old order by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella expelling all Jews from Spain who did not convert to Catholicism.

In June, when Tom Hayden had called for “two, three, many Columbias,” he had added that the goal was “so that the U.S. must either change or send its troops to occupy American campuses.” By December he was getting his second scenario. On December 5, after a week of riots and scuffles between police and students and faculty at San Francisco State College, armed policemen, weapons drawn, tossing canisters of Mace, began to clear the campus. Acting president S. I. Hayakawa, who had made his point of view clear when arriving in office a week before by denouncing the 1964 Free Speech Movement, told a crowd of more than two thousand students, “Police have been instructed to clear the campus. There are no innocent bystanders anymore.” The protests had begun with the demands of black students for black studies courses. For the last three weeks of the year the university was kept open only with a large armed police contingent regularly attacking students as they gathered to protest.

The nearby College of San Mateo, which was closed because of violence, reopened December 15, in the words of the school president, “as an armed camp,” with riot police stationed throughout the campus.

The most reviled president of a riot-torn campus, Columbia’s Grayson Kirk, who resigned in August, in December moved into a twenty-room mansion in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. The mansion had been provided by Columbia University, which owned the property.

In the beginning of December, the British, who had backed the Nigerian federal government, started to change their view of the Biafran war. While before they had been insisting on the imminent victory of Nigeria, they had now come to see the war as a hopeless stalemate. The United States also changed its policy. Johnson ordered contingency plans for a massive $20 million air, land, and sea relief program for Biafra. The French had already been supplying Biafra, which the Nigerians angrily said was the only thing keeping Biafra going. Supply planes for Biafra took off every night at 6:00

P.M.

from Libreville, Gabon. But Biafra was able to continue its fight for only one more year, and by the time it finally surrendered on January 15, 1970, an estimated one million civilians had starved to death.

After eleven months of negotiation, the eighty-two crew members of the U.S. ship

Pueblo

were released from North Korea in exchange for a confession by the U.S. government that it had been caught spying. As soon as the eighty-two Americans were safe, the U.S. government repudiated the statement. Some felt this was a strange way for a nation to conduct its affairs, and others felt it was a small price to pay to get the crew members released without a war. Left unclear was exactly what the

Pueblo

was doing when seized by the North Koreans.

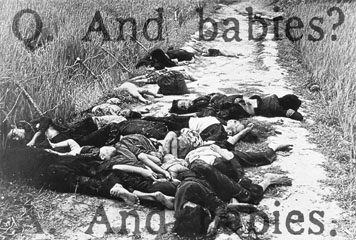

1970 poster, after the My Lai massacre became known. Frazer Dougherty, Jon Hendricks, and Irving Pettin designed the poster from an R. L. Haeberle photograph.

(Collection of Mary Haskell)

In Vietnam word of the massacre carried out by the Americal Division in My Lai in March continued to spread through the region. In the fall, the letter from Tom Glen of the 11th Brigade reporting the massacre was in division headquarters, and the new deputy operations officer for the Americal Division, Major Colin Powell, was asked to write a response. Without interviewing Glen, he wrote that there was nothing to the accusations—they were simply unfounded rumors. The following September, only nine months later, Lieutenant William Calley was charged with multiple murders, and by November it had become a major story. Yet Powell claimed he never heard about the massacre until two years after it happened. Nothing of Powell’s role in the cover-up—he was not even in Vietnam at the time of the massacre—was known by the public until

Newsweek

magazine reported it in September 1995 in connection with rumors of a Powell run for president.

Despite Johnson’s November announcement of a unilateral halt to bombing of North Vietnam and the expressed hope that this would lead to intense and productive negotiations, on December 6 the Selective Service announced that the draft call was to be increased by three thousand men a month. By mid-December peace negotiators in Paris were saying that Johnson had “oversold” the prospects for peace as the election approached.

In Paris the year-end peace negotiations had settled down to a tough and determined effort to resolve . . . the table issue. Hanoi was determined to have a square table, and that was completely unacceptable to South Vietnam. Other proposals debated by the different delegations included a round table, two arcs facing each other but not separated, or facing but separated. By the end of the year eleven different configurations were on the metaphoric table, which was still the only one they had. Behind the table issue were thornier realities, such as the North Vietnamese insistence on a Viet Cong presence, while the Viet Cong refused to speak with South Vietnam but were willing to speak with the Americans.

Senator George McGovern, the last-minute peace candidate at the Chicago convention, blurted out what many were trying to avoid saying when he called South Vietnamese vice president Nguyen Cao Ky a “little tinhorn dictator” and accused him and other South Vietnamese officials of holding up peace negotiations. “While Ky is playing around in the plush spots of Paris and haggling over whether he is going to sit at a round table or a rectangular table, American men are dying to prop up his corrupt regime back home.” It had been the policy of the antiwar senators to avoid speaking plainly about the South Vietnamese, some out of respect for Johnson, others to avoid upsetting negotiations. With Johnson out of power, they intended to speak more plainly. Some said they wanted to wait until Nixon’s inauguration, but McGovern started speaking two weeks early. A Gallup poll showed that a narrow majority of Americans now favored withdrawal and leaving the fighting to the South Vietnamese.

McGovern urged that there be a thoughtful assessment of the lessons of Vietnam. To him one of the great lessons was “the peril of drawing historical analogies.” Although there was no parallel between what was happening in Southeast Asia in the early 1960s and Europe in the late 1930s, the World War II generation became mired in a Vietnamese civil war in part because they had witnessed the appeasement of Hitler.

McGovern said, “This is a war of the daily body count, given to us over the years like the football scores.” The military understood that this too had been a mistake. They had even exaggerated the body counts. Future wars would appear to be as bloodless as possible, with the military saying as little as possible about enemy dead.

The military was learning its own lessons, not all of which were what McGovern had in mind when he tried to open this discussion. The military concluded that in a television age, journalists would have to be much more tightly controlled. The image of warfare had to be monitored carefully. Generals would have to consider how a battle looked on television and how to control that view.

The idea of a drafted army would be abandoned because it produced too many reluctant soldiers and too much adverse public opinion. It was better to have an all-volunteer military, drawn mostly from a few segments of society, people in need of employment and career opportunities. Wars would cease to be a major issue on campuses when students were no longer asked to fight.

But warfare was also to be used only against relatively defenseless countries, where technological superiority was critical, against enemies that would offer weeks, not years, of resistance.

The year 1968 ended exactly as it began, with the United States accusing the Viet Cong of violating its own Christmas cease-fire. But during the course of this year, 14,589 American servicemen died in Vietnam, doubling the total American casualties. When the United States finally withdrew in 1973, 1968 remained the year with the highest casualties of the entire war.

At the end of the year, Czechoslovakia was still defiant. A nationwide three-day sit-in strike by one hundred thousand students was supported by brief work stoppages by blue-collar workers. Dub ek made a speech saying that the government was doing its best to bring back reform but that the population should stop acts of defiance because they only led to repression. In truth, by December, when travel restrictions were put back in place, the last of the reforms had been undone. On December 21 Dub

ek made a speech saying that the government was doing its best to bring back reform but that the population should stop acts of defiance because they only led to repression. In truth, by December, when travel restrictions were put back in place, the last of the reforms had been undone. On December 21 Dub ek addressed the Central Committee of the Slovak Communist Party, his last speech of 1968. He was still resolute that the reforms must go through and that they would build a communist democracy. With the exception of a few references to “current difficulties,” the speech could have been written when the Prague Spring was in full bloom. He said:

ek addressed the Central Committee of the Slovak Communist Party, his last speech of 1968. He was still resolute that the reforms must go through and that they would build a communist democracy. With the exception of a few references to “current difficulties,” the speech could have been written when the Prague Spring was in full bloom. He said:

We must, as a permanent positive feature of the post-January policy, consistently ensure fundamental rights and freedoms, observe Socialist legality, and fully rehabilitate unjustly wronged citizens.

He urged everyone to go home, spend time with their families, and get some rest. In 1969 Dub ek was removed from office. In 1970 he was dismissed from the Communist Party. He and the reforms, “socialism with a human face,” slowly vanished into history. Mlyná

ek was removed from office. In 1970 he was dismissed from the Communist Party. He and the reforms, “socialism with a human face,” slowly vanished into history. Mlyná , who resigned his post in November 1968, realizing that he would no longer be able to pursue any of the policies he had wanted, said, “We were really fools. But our folly was the ideology of reform Communism.”

, who resigned his post in November 1968, realizing that he would no longer be able to pursue any of the policies he had wanted, said, “We were really fools. But our folly was the ideology of reform Communism.”