1968 (62 page)

When Trudeau died in 2000 at the age of eighty, both former

president Jimmy Carter and Cuban leader Fidel Castro were

honorary pallbearers.

The Beatles also surprised everyone with their lack of

stridency, or lack of commitment, depending on the point of

view. In the fall of 1968 they released their first

self-produced record—a single with

“Revolution” on one side and “Hey,

Jude” on the other. “Revolution” carried the

message “We all want to change the world”—but

we should do it moderately and slowly. The Beatles were

attacked for the stance in many places, including the official

Soviet press, but by the end of 1968 many people agreed. By the

fall, when there is usually a sense of renewal, there was

instead a feeling of weariness.

Not everyone felt it. Student activists returned to school

hoping to resume where they had left off in the spring, while

the schools hoped to go back to the way things were before.

When the Free University of Berlin opened in mid-October, the

women’s dormitories had been occupied by men for most of

the summer. The university gave in and announced that the

dormitories would henceforth be coeducational.

At Columbia, the radical students hoped to continue and

even internationalize the movement. In June the London School

of Economics and the BBC had invited New Left leaders from ten

countries to a debate it called “Students in

Revolt.” Student movements seized on this opportunity.

Opponents such as de Gaulle talked of an international

conspiracy, and the students thought this might be a good idea.

The fact was, they had mostly never met one another, except

those who had gone to Berlin for the spring anti-Vietnam

march.

Columbia SDS had decided to send Lewis Cole, as Rudd said

impatiently, “because he chain-smoked

Gauloises.

” In truth, Cole was the group intellectual most fluent

in Marxist theory. Cole and Rudd were being regularly invited

on the better talk shows such as David Susskind and William

Buckley.

At Columbia, SDS students felt the need for an ideology

that fit their action program. Martin Luther King had had his

moral imperative, but since these students hadn’t come

from religious backgrounds, this approach did not suit most of

them. The communist approach of being part of a great party,

the great movement—was too authoritarian. The Cuban

approach was too militaristic. “There was an idea in SDS

that we have the practice but the Europeans have the

theory,” said Cole. Cohn-Bendit had the same view. He

said, “The Americans have no patience for theory. They

just act. I was very impressed with this American Jerry Rubin,

just do it.” But at Columbia, where the students had been

so successful at getting attention, they were feeling the need

for an underlying theory that could explain why they were doing

the things they did. Cole admitted to a feeling of intimidation

at the prospect of debating with skilled European

theoreticians.

The London meeting was almost stopped by British

immigration, which tried to keep the radicals out. The Tories

did not want to let Cohn-Bendit in, but James Callaghan, the

home secretary, interceded on his behalf, saying that exposure

to British democracy would be good for him. Lewis Cole was

stopped at the airport, and the BBC had to contact the

government to get him in.

Cohn-Bendit immediately clarified to the press that they

were not leaders but rather “megaphones, you know,

loudspeakers of the movement,” which was an accurate

description of himself and many of the others. Cohn-Bendit

engaged in a put-on. De Gaulle had first come to prominence in

June 1940 when he left France, and in exile in Britain he made

a famous broadcast to the French people asking them to keep

resisting the Germans and not to follow the collaborationist

government of Philippe Pétain. Cohn-Bendit now announced

that he was asking for British asylum. “I will ask the

BBC to reorganize the Free French radio as they did during the

war.” He said that he would copy de Gaulle’s exact

message, except that where he had said “Nazis” he

would say “French fascists” and where he had said

“Pétain” he would say “de

Gaulle.”

The debate was dominated by Tariq Ali, the Pakistani-born

British leader who had once been president of the famous

debating society the Oxford Union. Ali said that students

renounced elections as a means for social change.

Afterward they all went to the grave of Karl Marx and had

their picture taken.

Cohn-Bendit returned to Germany vowing that he would

renounce his leadership and disappear into the movement. He

said that he had fallen prey to “the cult of

personalities” and that “power corrupts.” He

told the

Sunday Times

of London, “They don’t need me. Whoever heard of

Cohn-Bendit five months ago? Or even two months

ago?”

Cole found it a confusing experience. He never did

understand what Cohn-Bendit’s ideology was, and he found

Tariq Ali’s debating skills offputting. The people he

connected with most were from the German SDS, and he toured

Germany afterward with “Kaday” Wolf. “In the

end,” he said, “the ones with the greatest

similarities were the Germans. And the Germans had a lot of the

same cultural influences—Marcuse and Marx. And an intense

feeling of youth being incredibly alienated. A young person in

young dress walks down a street in Germany and the older

Germans just glared at him.”

But by fall Cole was back at Columbia with a theory he had

gleaned from the French called “exemplary action.”

The French had done exactly what the Columbia students were

trying to do—analyze what they had done and evolve a

theory from their actions. The theory of “exemplary

action” was that a small group could take an action that

would serve as a model for larger groups. Seizing Nanterre had

been such an action.

Traditional Marxist-Leninism is contemptuous of such

theories, which it labels “infantilism.” In June

Giorgio Amendola, a theoretician and member of the steering

committee of the Italian Communist Party, the largest Communist

Party in the West, attacked the Italian student movement for

“extremist infantilism” and scoffed at the idea

that they were qualified to lead a revolution without having

built their mass base in the traditional Marxist approach. He

termed it “revolutionary dilettantism.” Lewis Cole

said, “Exemplary action gave us our first theory. That

was why we had so many meetings. The question was always, what

do we do now?”

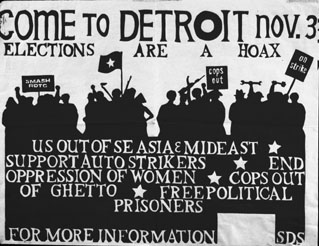

SDS poster announcing a demonstration before election

day, 1968

(Center for the Study of Political Graphics)

With their theory now in place, they were ready to be a

revolutionary center to prepare, as Hayden had said,

“two, three, many Columbias.” The theory also

helped the national office of the rapidly growing SDS become

more of a command center. The first action at Columbia was a

demonstration against the invasion of Prague. But that was

still in August, and few people came. According to Cole,

“It wasn’t very well done. The slogan was

‘Saigon, Prague, the pig is the same all over the

world.’”

Columbia SDS, looking for an event to restart the movement,

came up with the idea of hosting a student international, but

from the outset it was a disaster. Two days before the

conference began, the news broke of the student massacre in

Mexico. Columbia students, feeling guilty because they had not

even known that there was a student movement in Mexico, tried

to organize a demonstration at the conference. But they were

unable to come up with any consensus. The French situationists

spent the second day doing parodies of everyone who spoke. To

some, it was a welcome diversion from too much speaking. Cole

recalled, “We found that there were huge differences

between all of us. All we could agree on was

antiauthoritarianism, and alienation from society, these sorts

of cultural issues.” Increasingly, the other delegations

grew irritated at the French, especially the Americans, who

felt the French were lecturing them on Vietnam and failing to

understand what a burning issue it was in the United

States.

In Mark Rudd’s assessment, “The Europeans were

too pretentious, too intellectual. They only wanted to talk. It

was more talk. People made speeches, but I realized nothing

would happen.”

Rudd had no doubt that he was at a historic moment, that a

revolution was slowly unfolding and his job was to help it

along. A bit of Che—“The first duty of a

revolutionary is to make a revolution”—mixed with

the notion called “bringing the war home” and the

theory of exemplary action, and in June 1969 he came up with

the Weathermen, a violent underground guerrilla group named

after the Bob Dylan lyrics “You don’t need a

weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” In March

1970 they changed their name to the Weather Underground because

they realized that the original name was sexist. In hindsight,

it seems evident that a guerrilla group started by middle-class

men and women who name their group from a Bob Dylan song will

likely be their own worst enemies. Their only victims were

three of their own, who blew themselves up making bombs in a

house in Greenwich Village. But others turned to violence as

well. The government was violent. The police were violent. The

times were violent and revolution was so close. David Gilbert,

who had first knocked on Rudd’s dormitory door to recruit

him for SDS, continued after the mid-1970s when the Weather

Underground dissolved and more than twenty years later was

still in prison for his part in a fatal 1981 shootout. Many

1968 student radicals became 1970s underground guerrilla

fighters in Mexico, Central America, France, Spain, Germany,

and Italy.

Politics sometimes has longer tentacles than imagined.

That fateful first day of spring when Rockefeller collapsed the

earth from under the liberal wing of the Republican Party

unleashed a chain of events that the United States has been

living with ever since. A new kind of Republican was born in

1968. That became clear at the end of June, when President

Johnson appointed Justice Abe Fortas to succeed Earl Warren as

chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Warren had resigned

before the close of the Johnson administration because he

believed Nixon would win and he did not want to see his seat

taken over by a Nixon appointee. Fortas was a predictable

choice, a friend of Johnson, who had appointed him to replace

Arthur Goldberg three years earlier. Fortas had distinguished

himself as a leader of the liberal activist judges who had

characterized the Court since the mid-1950s. Although he was

the fifth Jewish justice on the Court, he would have been the

first Jewish chief justice.

At the time, the Senate rarely battled over Court

appointments. Both Republican and Democratic senators

recognized the right of the president to have his choice. In

fact, there had not been a battle since John J. Parker, Herbert

Hoover’s appointee, was rejected by two votes in

1930.

But when Fortas was named there was an immediate outcry of

“cronyism.” Fortas was a long-standing friend and

adviser to the president, but he was also eminently qualified.

The charge of cronyism was more effective against

Johnson’s other appointment to take Fortas’s seat,

Homer Thornberry. Thornberry was an old friend of Johnson, who

had advised him not to accept the vice presidential nomination

and then changed his mind and was at Johnson’s side when

he was sworn in as president after John Kennedy’s death.

A congressman for fourteen years, he became an undistinguished

circuit court judge. He had been a segregationist until Johnson

came to power and then reversed his stance, coming out on the

desegregation side of several notable cases.

But cronyism was not the main issue; it was the right of

Johnson to appoint Supreme Court justices. Republicans, who had

been in the White House only eight of the past thirty-six

years, felt they had a good chance of taking over in 1968, and

some Republicans wanted their own judges. Robert Griffin,

Republican from Michigan, got nineteen Republican senators to

sign a petition saying that Johnson, with only seven months

left in office, should not get to pick two judges. There was

absolutely nothing in law or tradition to back up this

position. At that point in the twentieth century, Supreme Court

judges had been appointed in election years six times. William

Brennan had been named by Eisenhower one month before the

election. John Adams picked his friend John Marshall, one of

the most respected appointments in history, only weeks before

Jefferson was to take office. Griffin simply wished to deny

Johnson his appointments. “Of course, a lame duck

president has the constitutional power to submit nominations

for the Supreme Court,” argued Griffin, “but the

Senate need not confirm them.” But Griffin and his

coalition of right-wing Republicans and southern Democrats were

not doing this completely on their own. According to John Dean,

who later served as special counsel to President Nixon,

candidate Nixon kept in regular contact with Griffin through

John Ehrlichman, later the president’s chief adviser on

domestic affairs.