1968 (64 page)

With the election only weeks away, the Humphrey-Muskie

campaign started running peculiar but effective print ads.

Never before had a front-runner been attacked in quite this

way. “Eight years ago if anyone told you to consider Dick

Nixon, you’d have laughed in his face.” It went on

to say, “November 5 is Reality Day. If you know, deep

down, you cannot vote for Dick Nixon to be President of the

United States you’d better stand up now and be

counted.” The ad included a campaign contribution coupon

that read, “It’s worth

to keep Dick Nixon from becoming President of the United

States.”

George Wallace was the wild card. Would he draw away enough

southern voters to deny Nixon states, thus ruining his southern

strategy? Or was he, like the old States’ Rights Party,

going to draw away traditional southern Democrats still loyal

to the old party? Wallace told southern crowds that both Nixon

and Humphrey were unfit for office because they supported civil

rights legislation, which to cheering crowds he termed

“the destruction of the adage that a man’s home is

his castle.” Nixon had called Wallace “unfit”

for the presidency. Wallace responded by saying that Nixon

“is one of those Eastern moneyed boys that looks down his

nose at every Southerner and every Alabamian and calls us

rednecks, woolhats, peapickers and peckerwoods.”

Ironically, Nixon himself always thought he was up against

“Eastern moneyed boys” himself.

Out of despair came frivolity. Yetta Brownstein of the

Bronx ran as an independent, saying, “I figure we need a

Jewish mother in the White House who will take care of

things.” There was a large bloc of people whose feelings

about the election were best expressed by the candidacy of

comedian Pat Paulsen, who said with his sad face and droning

voice, “I think I’m a pretty good candidate because

first I lied about my intention to run. I’ve been

consistently vague on all the issues and I’m continuing

to make promises that I’ll be unable to fulfill.”

Paulsen deadpanned, “A good many people feel that our

present draft laws are unjust. These people are called

soldiers. . . .” His campaign began as a routine on

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,

a popular television show. With Tom Smothers as his official

campaign manager, Paulsen on the eve of the election was

predicted by pollsters to attract millions of write-in

votes.

In the last two weeks of the campaign, polls started to

show that Nixon was losing that mystical mandate known in

political races and baseball series as “momentum.”

The fact that Nixon’s numbers were stagnant and

Humphrey’s continuing to grow implied a trend that could

propel Humphrey.

The campaigns for the House of Representatives were gaining

attention, becoming better financed and more contentious than

they had been in many years. The reason was that there was a

possibility, if Humphrey and Nixon ended up very close in

electoral votes, with Wallace taking a few southern states,

that no one would have a majority of state electoral votes, in

which case the winner would be picked by the House. The voting

public did not find this a very satisfying outcome. In fact, a

Gallup poll showed that 81 percent of Americans favored

dropping the electoral college and having the president elected

by popular vote.

But on election day, Wallace was not an important factor.

He took five states, denying them to Nixon, and Nixon swept the

rest of the South except Texas. While the popular vote was one

of the closest in American history—Nixon’s margin

of victory was about .7 percent—he had a comfortable

margin in the electoral college. The Democrats kept control of

both the House and Senate. Only 60 percent of eligible voters

bothered to cast votes at all. Two hundred thousand voters

wrote in for Pat Paulsen.

The Czechs saw the victory of Nixon, the old-time cold

warrior, as a confirmation of U.S. opposition to Soviet

occupation. Most Western Europeans worried that the change in

the White House would slow down Paris peace talks. Developing

nations saw it as a reduction in U.S. aid. Arab states were

indifferent because Nixon and Humphrey were equally friendly to

Israel.

Shirley Chisholm was elected the first black woman member

of the House. Blacks gained seventy offices in the South,

including the first black legislators in the twentieth century

in Florida and North Carolina and three additional seats in

Georgia. But Nixon won a clear majority of southern white

votes. The strategy that undid Abe Fortas also elected Nixon,

and it became

the

strategy of the Republican Party. The Republicans get the

racist vote and the Democrats get the black vote, and it turns

out in America there are more racist voters than black ones. No

Democrat since John F. Kennedy has won a majority of white

southern votes.

This is not to say that all white southern voters are

racist, but it is clear what votes the Republicans pursue in

the South. Every Republican candidate now talks of

states’ rights. In 1980 Ronald Reagan kicked off his

presidential campaign in an obscure, backwater rural

Mississippi town. The only thing this town was known for in the

outside world was the 1964 murder of Chaney, Goodman, and

Schwerner. But the Republican candidate never mentioned the

martyred SNCC workers. What did he talk about in Philadelphia,

Mississippi, to launch his campaign? States’ rights.

CHAPTER 21

THE LAST HOPE

I am more impervious to minor problems now; when two of my people come to me red-faced and huffing over some petty dispute, I feel like telling them, “Well, the earth continues to turn on its axis, undisturbed by your problem. Take your cue from it. . . .”

—M

ICHAEL

C

OLLINS,

Carrying the Fire,

1974

T

OM HAYDEN

later wrote about 1968, “I suppose it was fitting that such a bad year would end with the election of Richard Nixon to the presidency.” A Gallup poll showed that 51 percent of Americans expected him to be a good president. Six percent expected him to be “great,” and another 6 percent expected him to be “poor.” Nixon, looking exactly like the “Eastern moneyed boy” George Wallace accused the Californian of being, formed his cabinet from a thirty-nine-story-high luxury suite with a view of Central Park in New York’s Hotel Pierre, conveniently close to his ten-room Fifth Avenue apartment. A hardworking man, he rose at seven, ate a light breakfast, walked the block and a half to the Pierre, passed through the lobby, according to reports, “almost unnoticed,” and worked for the next ten hours. Among the visitors who seemed most to delight him was the University of Southern California star O. J. Simpson, the year’s Heisman Trophy winner who had run more yards than any other player in history. “Are you going to use that option pass, O.J.?” the president-elect wanted to know.

For the two thousand high-level positions just below the cabinet, he told his staff he wanted as broad a search as possible. Taking his instructions to heart, they had a letter drafted personally from Nixon asking for ideas and sent it to the eighty thousand people in

Who’s Who in America,

which led to news stories that Nixon was consulting Elvis Presley, who happened to be listed in the book. Though traditionally presidents revealed their cabinet choices gradually, one by one, Nixon, trying to tame that new media that had been troubling his career for a decade, arranged to have his entire cabinet announced at once from a Washington hotel with prime-time coverage on all three television networks.

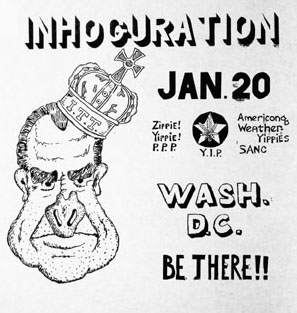

1968 Yippie poster calling for a demonstration at the Nixon inauguration

(Library of Congress)

This was one of his rare television innovations. However, he did show a strange affinity for another piece of technology, which in time was his undoing—the tape recorder. The Johnson administration had been fairly restrictive in the use of wiretapping and eavesdropping devices, but in the spring of 1968 Congress had passed a crime bill that greatly liberalized the number of federal agencies that could use such devices and the circumstances under which they could be used. Johnson had signed the bill on June 19 but said he believed that Congress “has taken an unwise and potentially dangerous step by sanctioning eavesdropping and wiretapping by federal, state, and local officials in an almost unlimited variety of situations.” Even after the bill passed, he instructed Attorney General Ramsey Clark to continue restricting the use of listening devices. But President-elect Nixon criticized the Johnson administration for not using the powers given by the new crime bill. Nixon called wiretaps and eavesdropping devices “law enforcement’s most effective tool against crime.”

He also had new ideas for listening devices. In December Nixon aides announced a plan to place listening posts in Birmingham, Alabama, and in Westchester County, New York, so that the president-elect could hear from “the forgotten American.” The plan was for volunteers to tape conversations in a variety of neighborhoods, town meetings, schools, and gatherings so the president-elect could hear Americans talking. “Mr. Nixon said that he would find a way for the forgotten man to talk to government,” a Westchester volunteer said.

The Chicago convention remained at the heart of one of America’s increasingly hot debates, the so-called law and order issue. While revulsion at the comportment of Daley and the Chicago police was the first reaction to the riots, increasing numbers argued that Daley and his police were right to impose “law and order.” In early December a government commission headed by Daniel Walker, vice president and general counsel of Montgomery Ward, issued its report on the Chicago riots under the title

Rights in Conflict.

The report concluded that the incident was nothing short of a “police riot” but also that the police were greatly provoked by protesters using obscene language. Not only the Left but the establishment press pointed out that police are quite accustomed to obscene language and wondered if this could really have been the cause for what seemed to be a complete breakdown of discipline. Mayor Daley himself was known to use unpublishable and unbroadcastable language.

The report described victims escaping from the police and the police responding by beating the next person they could find. It never did explore why McCarthy workers and supporters were targeted.

Life

magazine reported that the most corrupt police divisions were the most violent, implying that these were “bad cops” who did not take orders. But many of the demonstrators, including David Dellinger, remained convinced that far from a breakdown in discipline, “organized police violence was part of the plan,” as Dellinger testified to Congress.

On the other side, there were still many people who believed the Chicago police were completely justified in their actions. So the Walker Report neither healed, resolved, nor clarified. The House Un-American Activities Committee conducted its own hearings, subpoenaing Tom Hayden and others from the New Left, though they did not hear from Jerry Rubin because he arrived in a rented Santa Claus costume and refused to change out of it. Abbie Hoffman was arrested for wearing a shirt patterned after an American flag. He was charged on a newly passed law making it a federal crime to show “contempt” for the flag. The committee’s acting chairman, Missouri Democrat Richard H. Ichord, said that the Walker Report “overreacted,” as did newsmen who covered the story. The keen eyes of the House Un-American Activities Committee had, not surprisingly, uncovered that the whole thing was a communist plot. Their evidence: Dellinger and Hayden had met with North Vietnamese and Viet Cong officials in Paris. “Violence follows these gentlemen just as night follows day,” Ichord said, waxing nearly Shakespearean.

The Government Printing Office refused to print the Walker Report because the commission refused to delete the obscenities that witnesses accused demonstrators and police of shouting at one another. Walker said that deleting the words would “destroy the important tone of the report.” Daley himself praised the report and criticized only the summary. As he walked out of the press conference, reporters shouted, “What about your police riot?” But the mayor had no comment.

The law with which Abbie Hoffman was arrested for his shirt was one of several laws passed by Congress to harass the antiwar movement, as Republicans and Democrats competed for the “law-and-order” vote in an increasingly repressive United States. Another of these 1968 laws made it a crime to cross state lines with the intent to commit violence. Federal prosecutors in Chicago were considering charging the leaders of the Chicago demonstrations with this untested law. But Johnson’s attorney general Ramsey Clark had no enthusiasm for such a conspiracy trial. This changed when Nixon took office and appointed New York bonds lawyer John Mitchell attorney general. Mitchell once said that Clark’s “problem” was that “he was philosophically concerned with the rights of the individual.” He wanted a Chicago conspiracy trial and on March 20, 1969, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale, John Froines, and Lee Weiner—who came to be known as the “Chicago Eight”—were indicted. Hayden, Davis, Dellinger, Hoffman, and Rubin openly admitted organizing the Chicago demonstrations but denied causing the violence that even the government’s Walker Report blamed on the police. But they barely knew Black Panther leader Bobby Seale. During the trial, Judge Julius Hoffman ordered Seale bound and gagged for repeatedly calling Hoffman a fascist. None of them understood how SDS activists Froines and Weiner had gotten on the list and in fact the two were the only ones acquitted. The others had their convictions reversed on appeal. But John Mitchell himself later went to prison for perjury in the Watergate investigation.

The Italians for a brief moment in November were gripped by the story of Franca Viola, who married the man she loved, a former schoolmate. Two years earlier she had rejected the son of a wealthy family, Filippo Melodia, so he kidnapped her and raped her. After being raped, a woman had to marry her aggressor because she had been dishonored and no one else would have her. This approach had worked for Sicilian men for about a thousand years. But Franca, to the applause of much of Italy, went into court and said to Melodia, “I do not love you. I will not marry you.” This came as a blow to Melodia, not only because he had been rejected, but because under Sicilian law, if the woman doesn’t marry the rapist, he is then tried for rape, a crime for which Melodia was sentenced to eleven years in prison.

On December 3 strikes and protests by both workers and students paralyzed Italy after two striking workers were shot and killed in Sicily. An anarchist bomb destroyed a government food office in Genoa. The bombers left flyers that said, “Down with Authority!” By December 5 Rome was closed by a general strike. But by December 6 the workers had ended their strike for higher wages and left tens of thousand of protesting students on their own.

In France, too, the idea of merging the worker and student movements was still alive but still failing. On December 4, Jacques Sauvageot met with union leaders in the hopes of building the unified front that had failed in the spring. De Gaulle had been artificially propping up the franc for more than a year simply because he believed in “the strong franc,” and it was now seriously overvalued and declining rapidly in world currency markets. Instead of the normal fiscal maneuver of devaluing, he shocked Europe and the financial world by instituting a series of drastic measures to reduce social spending in order to try to uphold the declining currency. French workers were furious. On December 5 strikes began. But by December 12 the government had negotiated an end to the strikes and the students again found themselves alone when they shut down Nanterre to protest police attempts to interrogate students. The French government threatened to start expelling “student agitators” from the universities.

With each blow, it was predicted that de Gaulle would be tamed—when his prestige declined after the spring riots and strikes, when his foreign policy was shaken by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, when his economy was undone by the collapse of the franc. Yet at the end of the year, to the utter frustration of his European partners, he blocked British entry into the Common Market for the third time.

On November 7 Beate Klarsfeld, the non-Jewish German wife of French Jewish survivor and celebrated Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld, went to the social democrats convention in Berlin, walked up to Chancellor Kiesinger, accused him of being a Nazi, and slapped him in the face. By the end of 1968 the West German state had sent to prison 6,221 Germans for crimes committed during Nazi rule—a considerable number of convictions, but a minuscule percentage of Nazi criminals. In 1968 the West German state convicted a total of only thirty Nazis, almost all minor, obscure figures. Despite the numerous very active and murderous Nazi courts during Hitler’s rule, not a single judge had ever been sent to prison. On December 6 a Berlin court acquitted Hans Joachim Rehse, a Nazi judge who had sentenced 230 people to death. The prosecution had chosen to try him on seven of the more arbitrary and flagrant abuses of justice, but the court ruled that the prosecution had shown only abuse of the law, not the intention to do so. The decision was based on an earlier case in which it was ruled that judges were not guilty “if they were blinded by Nazi ideology and the legal philosophy of that time.” As Rehse left the courtroom, a crowd chanted, “Shame! Shame!” and an elderly man walked up and slapped him across the face. The following week eight thousand marched through Berlin to the city hall to protest Rehse’s release. There was little time left. The federal statute for prosecuting Nazi crimes was to expire in one more year, December 31, 1969.

During the summer of 1968, the Spanish government had placed the Basque province of Guipúzcoa under indefinite martial law. In the village of Lazcano, the village priest denounced the organist for having played the Spanish national anthem during “the elevation of the sacrament.” The priest was fined for his criticism, which was easily arranged since the organist also happened to be the mayor of the village. While the mayor was away, his house was burned down. Five young Basques were arrested and held for five days. According to witnesses, they were handcuffed to chairs and kicked and beaten for three of those days. They confessed. The prosecution asked for death sentences in a trial that presented no evidence other than police testimony. In December three were sentenced to forty-eight years in prison, one was sentenced to twelve years, and one was acquitted.