100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (2 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

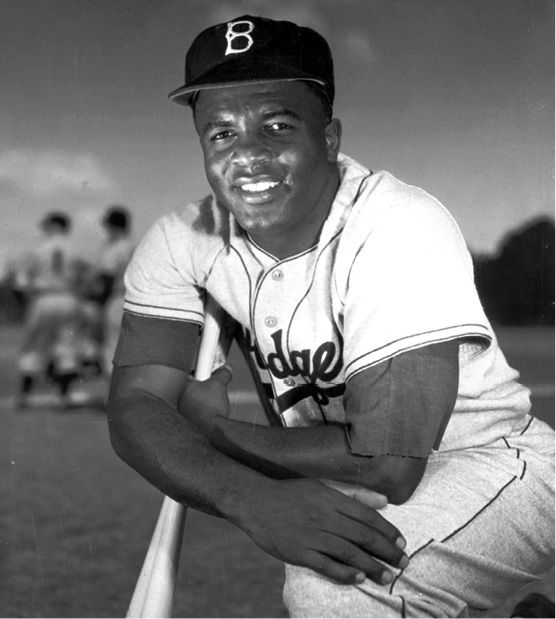

1. Jackie

From beginning to end, we root for greatness.

We root for our team to do well. We root for our team to create and leave lasting memories, from a dazzling defensive play in a spring training game to the final World Series-clinching out. With every pitch in a baseball game, we're seeking a connection to something special, a fastball right to our nervous system.

In a world that can bring frustrations on a daily basis, we root as an investment toward bragging rights, which are not as mundane as that expression makes them sound. If our team succeeds, if our guys succeed, that's something we can feel good about today, maybe tomorrow, maybe forever.

The pinnacle of what we can root for is Jackie Robinson.

Robinson is a seminal figureâa great player whose importance transcended his team, transcended his sport, transcended all sports. We don't do myths anymore the way the Greeks didâtoo much reality confronts us in the modern age. But Robinson's story, born in the 20

th

century and passed on with emphasis into the 21

st

, is as legendary as any to come from the sports world.

And Robinson was a Dodger. If you're a Dodgers fan, his fable belongs to you. There's really no greater story in sports to share. For many, particularly in 1947 when he made his major league debut, Robinson was a reason to become a Dodger fan. For those who were born or made Dodgers fans independent of Robinson, he is the reward for years of suffering and the epitome of years of success.

Robinson's story, of course, is only pretty when spied from certain directions, focusing from the angle of what he achieved, and what that achievement represented, and the beauty and grace and power he displayed along the way. From the reverse viewpoint, the ugliness of what he endured, symbolizing the most reprehensible vein of a culture, is sickening.

Â

Â

Â

As the first African American major league ballplayer, Jackie Robinson proved time and again his talents and integrity were superhuman both on and off the field. Playing nearly every position on the field over 10 seasons, Jackie Robinson was an indispensable contributor to the Dodgers' six pennants and the franchise's first World Series victory.

Â

Before Robinson even became a major leaguer, he was the defendant in a court martial over his Rosa Parks-like defiance of orders to sit in the back of an Army bus. His promotion to the Dodgers before the '47 season was predicated on his willingness to walk painstakingly along the high road when all others around him were zooming heedlessly on the low.

Even after he gained relative acceptance, even after he secured his place in the major leagues and the history books, even after he could start to talk back with honesty instead of politeness, racial indignities abounded around him. Robinson's ascendance was a blow against discrimination, but far from the final one. He still played ball in a world more successful at achieving equality on paper than in practice. It's important for us to remember, decades later, not to use our affinity for Robinson as cover for society's remaining inadequacies.

Does that mean we can't celebrate him? Hardly. For Dodgers fans, there isn't a greater piece of franchise history to rejoice inâand heaven forbid we confine our veneration of Robinson to what he symbolizes. The guy was a ballplayer. Playing nearly every position on the field over 10 seasons, Robinson had an on-base percentage of .409 and slugging percentage of .474 (132+ OPS, .310 TAv). He was an indispensable contributor to the Dodgers' most glorious days in Brooklynâsix pennants and the franchise's first World Series victory.

It also helps to know that some of Robinson's moments on field were better than others, that he didn't play with an impenetrable aura of invincibility. He rode the bench for no less an event than Game 7 of the 1955 World Series. He was human off the field, and he was human on it.

In the end, Robinson's story might just be the greatest in the game. His highlight reelâfrom steals of home to knocks against racismâis unmatched. In a world that's all too real, Robinson encompasses everything there is to cheer for. If you're a fan of another team and you hate the Dodgers, unless you have no dignity at all, your hate stops at Robinson's feet. If your love of the Dodgers guides you home, Robinson is your North Star.

Â

Â

Robinson's Retirement

One of the great myths in Dodgers history is that Jackie Robinson retired rather than play for the team's nemesis, the New York Giants, after the Dodgers traded him there, seven weeks before his 38

th

birthday. In fact, as numerous sources such as Arnold Rampersad's Jackie Robinson: A Biography indicate, Robinson had already made the decision to retire and take a position as vice president of personnel relations with the small but growing Chock Full O' Nuts food and restaurant chain. This happened on December 10, 1957. But Robinson had a preexisting contract to give

Look

magazine exclusive rights to his retirement story, which meant the public couldn't hear about his news until a January 8, 1958, publication date.

The night he signed his Chocktract, on December 11, Dodger general manager Buzzie Bavasi called Robinson to tell him he had been traded to the Giants. Teammates and the public reacted with shock to the news and rallied to his defense, even though Robinson had no intention of reporting. When the truth finally came out, it was Robinson who caught the brunt of the negative reaction at the time. Over the years, however, the story evolved into the fable that Robinson chose retirement because playing for the Giants was a moral impossibility. Robinson left baseball and the Dodgers nursed grievances over how he was treated. The trade to the Giants wasn't the last straw that drove him out, but rather an event that confirmed that the decision he had already made was well chosen.

2. Vin

He's an artist. Of course he's an artist. You don't need a book to tell you that the man could broadcast paint drying and turn it into something worthy of Michelangelo; to tell you that his voice is a cozy quilt on a cold morning, a cool breeze on a blistering day; that he's more than someone you listen to, that he's someone you feel.

But saying he's an artist is not meant as a cliché or as a convenient way to sum him up. It's meant to stress that spoken words at a baseball game are themselves an art form and, sure, sometimes they're the equivalent of dogs playing poker, but when Vin Scully strings words together (and he's done so at Dodger gamesâextemporaneously, mind youâfor 25,000 hours or more), they'll carry you away on wings.

If it weren't so satisfying, it could make you weep.

But it's not as if Vinnyâand at this point, it's hard to resist referring to him by his first name, so vital and personal is the Dodger fan's relationship with himâsets out to construct pieces for the Smithsonian. His principal goal has always been only to simply tell you what's going on. He'll never miss a pitch. He will make a mistake here and there, and in that respect he's like everyone else on the planet. But he never, ever loses sight of his task.

He is prepared with background on the players and the teams he covers. He has a knack for sifting out what's interesting about the men on the field, and has an infectious enthusiasm for what he discovers. Reflecting his desire not to leave any listeners or viewers in the dark, he'll repeat stories on different nights of the same series, but as long as you know that's part of the deal, there's no issue.

“One of the biggest reasons that I prepare is because I don't want to seem like a horse's fanny, as if I'm talking about something I don't know,” Scully said in an interview. “So in a sense you could say I prepare out of fear. That's really what you do. I think I've always done that since grammar school.”

Â

Â

Â

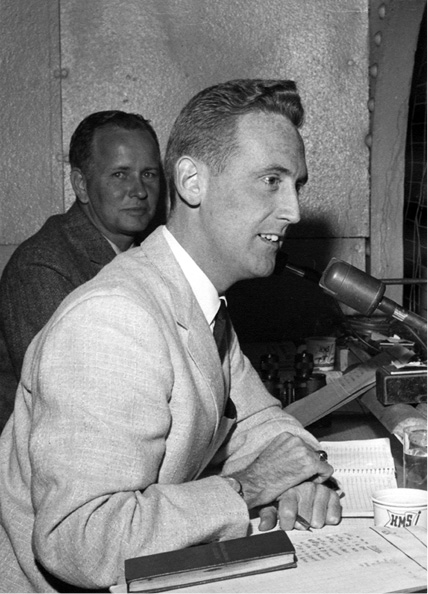

Vin Scully and Jerry Doggett broadcast the final game played at aging Ebbets Field in Brooklyn on September 24, 1957. Doggett worked alongside Scully from 1956â87.

Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Â

That may be equal parts humility and truth. Scully's utter genius, however, is the way he reacts when the moment takes him beyond preparation, the way he offers the lyrical when other broadcasters remain stuck in the trite. He offers

bon mots

covering pedestrian occurrencesâwho else could deliver baseball play-by-play's timeless philosophical comment: “Andre Dawson has a bruised knee and is listed as day-to-day.⦠Aren't we all?” His work during Sandy Koufax's perfect game, Hank Aaron's 715

th

home run, Bill Buckner's error, and everything in between are all unforced majesty.

As far as rising to the occasion, Scully's landmark call of Kirk Gibson's showstopping, history-making homer in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series was practically its equivalent from a broadcasting perspective, minus the gimpiness. “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened” ranks with Al Michaels' “Do you believe in miracles? Yes!” among the most memorable lines in sportscasting history for spontaneously summing up a moment. And yet, could anyone have been less surprised that Scully came up with such a wonderful remark? His broadcasts have been dotted with them ever since he joined the Brooklyn Dodger broadcast team in 1950 as a recent Fordham college graduate who had been singularly dreaming of such a job since boyhood.

“When I was 8 years old, I wrote a composition for the nuns saying I wanted to be a sports announcer,” Scully said. “That would mean nothing todayâeverybody watches TV and radioâbut in those days, back in New York the only thing we really had was college football on Saturday afternoons on the radio. Where the boys in grammar school wanted to be policemen and firemen and the girls wanted to be ballet dancers and nurses, here's this kid saying, âI want to be a sports announcer.' I mean it was really out of the blue.

“The big reason was that I was intoxicated by the roar of the crowd coming out of the radio. And after that one thing led to another, and I eventually got the job as third announcer in Brooklyn. And I never thought about anything except, the first year or two, not making some terrible mistake. I worked alongside two wonderful men in Red Barber and Connie Desmond, but I never thought about becoming great⦠All I wanted to do was do the game as best I could. And to this day that's all I think about.”

Lots of people try to do their best, and for that they all deserve praise. But the best of some is better than the best of others, and even though he can't bring himself to say it, we know into which of those categories Scully fits. Regardless of how intense or carefree one's love for the game might be, Scully measures up to and redoubles it. The Dodgers' play-by-play man is an American Master.

Â

Â

Koufax's Perfect Game: The Final Out, by Vin Scully

Audio of the entire ninth inningâwhich you really need to hearâcan be found online at http://www.triumphbooks.com/100ThingsDodgers

“He is one out away from the promised land, and Harvey Kuenn is comin' up.

“So Harvey Kuenn is batting for Bob Hendley. The time on the scoreboard is 9:44. The date, September the 9

th

, 1965, and Koufax working on veteran Harvey Kuenn. Sandy into his windup and the pitch: A fastball for a strike! He has struck out, by the way, five consecutive batters, and that's gone unnoticed. Sandy ready, and the strike one pitch: very high, and he lost his hat. He really forced that one. That's only the second time tonight where I have had the feeling that Sandy threw instead of pitched, trying to get that little extra, and that time he tried so hard his hat fell off. He took an extremely long stride to the plate, and Torborg had to go up to get it.

“One and one to Harvey Kuenn. Now he's ready: Fastball, high, ball two. You can't blame a man for pushing just a little bit now. Sandy backs off, mops his forehead, runs his left index finger along his forehead, dries it off on his left pants leg. All the while Kuenn just waiting. Now Sandy looks in. Into his windup and the 2â1 pitch to Kuenn: Swung on and missed, strike two!

“It is 9:46 PM

“Two and two to Harvey Kuenn, one strike away. Sandy into his windup, here's the pitch:

“Swung on and missed, a perfect game!”

After 39 seconds of cheering â¦

“On the scoreboard in right field it is 9:46 pm in the City of the Angels, Los Angeles, California. And a crowd of 29,139 just sitting in to see the only pitcher in baseball history to hurl four no-hit, no-run games. He has done it four straight years, and now he caps it: On his fourth no-hitter, he made it a perfect game. And Sandy Koufax, whose name will always remind you of strikeouts, did it with a flourish. He struck out the last six consecutive batters. So when he wrote his name in capital letters in the record books, that “K” stands out even more than the O-U-F-A-X.”

Â