You Mean I'm Not Lazy, Stupid or Crazy?!: The Classic Self-Help Book for Adults With Attention Deficit Disorder (4 page)

Authors: Kate Kelly,Peggy Ramundo

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Diseases, #Nervous System (Incl. Brain), #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #General, #Psychology, #Mental Health

I

t’s difficult to grow up with the hidden handicap of ADD. Many of us feel that we’ve spent our lives disappointing everyone—parents, siblings, teachers, friends and ourselves. When we were children, our teachers repeatedly told us we could do our work but chose not to. Our report cards were continual reminders that

we weren’t very bright. Those Cs, Ds and Fs didn’t lie. They defined our self-perception as kids who were lazy. Sometimes we felt smart. We came up with wonderful inventions and imaginative play. We often amazed ourselves, our teachers and our parents with our wealth of knowledge and creative ideas.

We didn’t want to cause trouble. We didn’t start our days with a plan to drive everyone crazy.

We didn’t leave our rooms in total chaos to make our parents wring their hands in frustration. We didn’t count the thumbtacks on the bulletin board because we enjoyed watching the veins pop out of a teacher’s neck when he yelled at us to get to work. We didn’t yawn and stretch and sprawl across our desktops, totally exhausted, just to make the other kids laugh. We didn’t beg for more toys, bigger

bikes or better birthday parties because we wanted our moms and dads to feel terrible for depriving us of these things.

We did these things because we had ADD. But unfortunately, most of us didn’t know that. Most of our parents, siblings,

teachers and friends didn’t know that either. So most of us grew up with negative feelings that developed around behaviors everyone misunderstood.

Pay attention.

Stop fooling around.

If you would just try, you could do it.

You’re lazy.

Settle down.

You can do it when you want to.

Why are you acting this way?

You’re too smart to get such terrible grades.

Why do you always make things so hard for yourself?

Your room is always a mess.

You just have to buckle down.

Stop bothering other children.

Are you trying to drive me crazy?

Why can’t you act like your brother/sister?

Why are you so irresponsible?

You aren’t grateful for anything.

Have you ever heard any of these comments? If you’re a parent, have you ever said any of them? Our bet is that your answer to both questions is a resounding “Yes!”

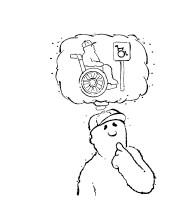

It’s unlikely that anyone would tell a child in a wheelchair that he could get up and walk if he tried harder. His handicap is obvious and everyone understands his limitations. Unfortunately, not many people understand the hidden

handicap of an ADD child.

PR:

“I have sometimes wished that my son had a physical handicap instead of ADD. Of course, I don’t really wish he had a physical disability. If he did, though, it would be easier to explain his challenges to people who don’t understand. It would be easier for me to understand.”

For most of us the misunderstandings and faulty assumptions continued into our adolescent

years. Since we were old enough to know better, our behaviors were tolerated even less. By the time we became adults, many of us were convinced that we indeed were—and still are—lazy, stupid or crazy.

Understanding Through Education

As we move through this book, we’ll offer many suggestions and strategies for dealing with ADD. But the first and most important one is to repeat at least a hundred

times:

“I am not lazy, stupid or crazy!”

If you aren’t convinced yet, we hope you will be by the end of this book. We hope you’ll be able to formulate a new, positive self-perception to replace the old one. Reframing your self-perceptions is your first job. To accomplish this, you’ll need an in-depth understanding of ADD.

To understand your symptoms and take appropriate steps to gain control

over them, you have to learn as much as you can about your disorder. Even if you’ve already done your homework

on ADD, we encourage you to read the following section. You may not discover new information per se, but you may discover a new framework for understanding specific issues of ADD in adults. We will use this framework as we examine the dynamics of ADD in your relationships, your workplace

and your home.

About Definitions, Descriptions and Diagnostic

Dilemmas: Is It ADD or ADHD?

ADD (or ADHD) is a disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by disturbances in the areas of attention, impulsiveness and hyperactivity.

Media focus gives the impression that ADD is a new problem. Some subscribe to the theory that ADD might not be new but is being used by increasing numbers

of parents to excuse their children’s misbehavior. In fact, when we first wrote this book, a local principal was referring to ADD as

just the yuppie disorder of the eighties

.

This observation would come as a surprise to Dr. G. F. Still, a turn-of-the-century researcher who worked with children in a psychiatric hospital. We doubt there were many yuppies in 1902 when Still worked with his hyperactive,

impulsive and inattentive patients. Although he used the label “A Defect in Moral Control,” he theorized that an organic problem rather than a behavioral one caused the symptoms of his patients. This was a rather revolutionary theory at a time when most people believed that bad manners and improper upbringing caused misbehavior.

In the first half of the twentieth century, other researchers supported

Dr. Still’s theory. They noted that various kinds of brain damage caused patients to display symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention. World War I soldiers with brain injuries and children with damage from a brain virus both had symptoms similar to those of children who apparently had been born with them.

Over the years, many labels have been given to the disorder. The labels have

reflected the state of research at the time:

Post-Encephalitic Disorder

Hyperkinesis

Minimal Brain Damage

Minimal Brain Dysfunction

Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood

Attention Deficit Disorder with and without Hyperactivity

The focus on structural problems in the brain—holes perhaps, or other abnormalities detected through neurological testing, persisted until the sixties. Then research began

to focus primarily on the symptom of hyperactivity in childhood. In 1968, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) responded to this research by revising its diagnostic manual (DSM-II). The revision included the new label: “Hyperkinetic Disorder of Childhood.”

During the seventies, research broadened its focus beyond hyperactivity and concluded that subtle cognitive disabilities of memory and

attention problems were the cores of the disorder. These conclusions, coupled with the discovery that attention problems could exist without hyperactivity and continue beyond childhood, required a second revision of the diagnostic manual.

In 1980, the APA’s revised manual, the DSM-III, created new labels: “ADDH, Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity”; “Attention Deficit Disorder Without

Hyperactivity” and “Residual Type” (for those whose symptoms continued into adulthood).

If your son was diagnosed in 1985 with ADDH, why was your daughter diagnosed in 1988 with ADHD? Are you confused yet? Well, you guessed it. The labels changed again in 1987, with the next version of the DSM, the DSM-III-R.

A number of experts believed that hyperactivity had to be present for an ADD diagnosis.

They theorized that the other related

symptoms were part of a separate disorder. In 1994, the DSM-IV made its appearance, reflecting this theory with yet another set of labels: ADHD, primarily inattentive type; ADHD, primarily hyperactive type; and ADHD, combined type. The DSM-IV is now in its fourth edition, called the DSM-IV-TR. Thank God, the DSM-V won’t be ready until at least 2011!

Is there

any reason to remember the DSM label revisions? We suppose you could drop terms like the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association

to impress friends at your next party! The information would be useful if you happen to be studying psychology and need the information for an upcoming exam. Otherwise, the only reason to know about the changing labels is that they reflect

an ever-changing understanding of ADD.

The debate will continue about ADD issues—what is it exactly and who should be included in the diagnostic criteria? To provide guidelines for diagnosticians, the APA’s manual attempts to label and describe various clusters of symptoms, assigning different groups into distinct categories of disorders.

The problem is that human beings don’t cooperate with

this attempt to categorize behavior. Behaviors just won’t fit into tidy little boxes. If you have ever agonized over naming your business report or the song you just composed, you know the limitations of a title. It’s difficult to capture the essence of something in a few words.

In practical terms, this means that relatively few people fit the classic DSM diagnoses. There is also much symptom

overlap

between

different disorders, so an individual may have symptoms of multiple disorders. The significance for an ADDer is that he shouldn’t expect his symptoms to be exactly like his child’s, friend’s or spouse’s.

For our purposes, we’ve made the decision to use the generic label “ADD” in this book. First, it’s easier to type than

“ADHD”! Second and more important, the ADD label avoids

the hyperactivity/no hyperactivity issue.

Specific Symptoms of ADD

As we review specific symptoms, you’ll become aware of the imprecision of definitions and descriptions, particularly as they apply to ADD in adults. One reason for this imprecision is the complex nature of the brain and central nervous system. This complexity creates a billion-piece jigsaw puzzle of possible causes and symptoms.

Each of us is a puzzle with an assortment of puzzle pieces uniquely different from another ADDer. Adding to the diagnostic dilemma are the rapid behavioral changes that make a precise description of the disorder difficult.

Despite the diagnostic dilemma, it is important to understand the impact ADD symptoms have on your life. You don’t have to be a walking encyclopedia of ADD, but you do need

sufficient knowledge to capitalize on your strengths and bypass your weaknesses. In the following section, we’ll examine the three major symptoms of ADD. In Chapter 2, we’ll take a broader look at an ADDer’s differences that don’t quite fit into the diagnostic criteria.

Inattention

Most people characterize an attention deficit disorder as a problem of a short attention span. They think of ADDers

as mental butterflies, flitting from one task or thought to another but never alighting on anything. In reality, attending is more than simply paying attention. And a problem with attending is more than simply not paying attention long enough.

It’s more accurate to describe attentional problems as components of the process of attention. This process includes

choosing

the right stimulus to focus

on,

sustaining

the focus over time,

dividing

focus between relevant stimuli and

shifting

focus to another stimulus. Impaired functioning can occur in any or all of these areas of attention. The result is a failure to pay attention.

Workaholism, single-mindedness, procrastination, boredom—these are common and somewhat surprising manifestations of attentional problems. It might seem paradoxical

that a workaholic could have attentional problems. It might seem paradoxical that a high-energy adult could have trouble getting started on his work.

These manifestations are baffling only if ADD is viewed as a short attention span or worse, an excuse. When

all

the dimensions of attention are considered, it becomes easier to understand the diversity of the manifestations of ADD.

The Workaholic

might have little difficulty selecting focus or sustaining it but have great difficulty shifting his focus. Unable to shift attention between activities, he can become engrossed in his job to the exclusion of everything else in his life.

Similar behavior can be seen in the person who has trouble sustaining attention. He struggles so intently to shut out the world’s distractions that he gets locked

in to behavior that continues long after it should stop. It’s as if he wears blinders that prevent him from seeing anything but the task at hand. The house might burn down and the kids might run wild but he’ll banish that last dust ball from the living room!

The Procrastinator

has the opposite problem. He can’t selectively focus his attention and might endure frequent accusations about his laziness.

In truth, he’s so distracted by stimuli that he can’t figure out where or how to get started. Sounds, smells, sights and the random wanderings of his thoughts continually vie for his attention.

Unable to select the most important stimulus, he approaches most tasks in a disorganized fashion and has trouble finishing or sometimes even starting anything. If the task is uninteresting, it’s even harder

for him to sustain focus.