What Hath God Wrought (18 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

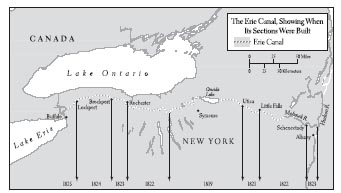

DeWitt Clinton called the Erie Canal “a work more stupendous, more magnificent, and more beneficial than has hitherto been achieved by the human race.” He might be forgiven an excess of rhetorical zeal; most contemporaries found the canal an extraordinary triumph of human art over nature. The completed canal ran for 363 miles (the longest previous American canal extended 26 miles); workers dug it forty feet wide and four feet deep, with eighteen aqueducts and eighty-three locks to overcome changes in elevation totaling 675 feet.

66

To make use of Lake Ontario for part of the course would have been cheaper, but planners feared that route would not be militarily secure in case of another war with Britain. Besides, once boats got into Lake Ontario they might be tempted to follow the St. Lawrence to Montreal instead of the Hudson to New York City. So the canal route reflected its designers’ policy as well as their technology. To the generation that built it and benefited from it, the canal exemplified a “second creation” by human ingenuity perfecting the original divine creation and carrying out its potential for human betterment. What man had wrought became, indirectly, what God had wrought.

67

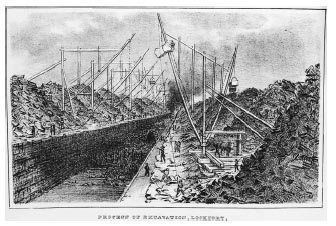

Work began at Rome, New York, at dawn on the Fourth of July 1817. The date was no accident: The canal’s promoters saw economic development as fulfilling the promise of the American Revolution. With no adequate engineering training available in the United States, the engineers and contractors learned as they went along. They dug the level central section of ninety-four miles first. When it came time to construct the more challenging eastern and western termini, toll revenues from the completed segments were already more than paying interest on the bonded debt the state had incurred. Contracts were let to local builders, sometimes for only a fraction of a mile of construction, to allow many small businessmen to participate. About three-quarters of the nine thousand laborers were upstate New Yorkers, native born Americans of Dutch or Yankee descent, perhaps surplus workers out of the agricultural sector whose sisters would go off to textile mills. The rest were mostly Irish immigrants, as almost all canal diggers would be within a generation. (On July 12, 1824, a riot erupted at Lockport between rival mobs of Catholic and Protestant Irish workmen.)

68

The Erie Canal represented the first step in the transportation revolution that would turn an aggregate of local economies into a nationwide market economy. Within a few years the canal was carrying $15 million worth of goods annually, twice as much as floated down the Mississippi to New Orleans.

69

Wheat flour from the Midwest was stored in New York alongside the cotton that the city obtained from the South through its domination of the coastal trade; both could then be exported across the Atlantic. New York merchants began to buy wheat and cotton from their producers before shipping them to the New York warehouses. Soon the merchants learned to buy the crops before they were even grown; that is, they would advance the grower money on the security of his harvest. Thus the city’s power in commercial markets fostered its development as a financial center.

Contemporary depiction of technology devised to dig the Erie Canal. The horse inside the base of the crane supplies power to lift debris blasted out by gunpowder. From Cadwallader Colden,

Memoir Prepared for the Celebration of the Completion of the New York Canals

, 1825. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Meanwhile, New York City had adopted (in 1817) an auction system for imports that made it attractive to merchants shipping high-quality textiles from Manchester and Leeds, iron, steel, and tools from Sheffield and Birmingham in England, or wines from continental Europe. Traditionally, passengers had to wait around a port city until their ship’s hold filled with cargo. Commencing in January 1818, a transatlantic service from New York to Liverpool provided passengers with scheduled sailings for the first time; people called its ships “packets” because they had a government contract to carry packets of mail. New York also came to outdistance Boston in the China trade. Finally, the founding of the New York Stock Exchange in 1817 made it easier for entrepreneurs to raise capital from investors. When the Erie Canal reinforced all these other developments, together they made New York the most attractive place in the country to do business on a large scale. Jobs multiplied, and as a result the city grew in population from 125,000 in 1820 to over half a million by 1850. New York had redrawn the economic map of the United States and put itself at the center.

70

V

The modern scholar Benedict Anderson has called nations “imagined communities.”

71

Certainly it required some imaginative power to think of the enormous and diverse extent of the United States as constituting a single nation in the days before the railroad and the telegraph. Many orators and politicians exercised their imagination in the creation of American nationalism. But no imagination of a unified national identity would have more lasting significance than the jurisprudence of the United States Supreme Court under Chief Justice Marshall.

In 1815, John Marshall turned sixty years old and had been chief justice for fourteen years. He had already made a huge mark in history through his assertion of judicial review. In

Marbury v. Madison

(1803) he had declared an act of Congress unconstitutional; even more importantly, he had extended this power to state legislation in

Fletcher v. Peck

(1810). Marshall had not been President Adams’s first choice for his job, and he had been confirmed without enthusiasm by the Federalist-controlled lame duck Senate of January 1801.

72

But while Federalism withered away as a party, and failed to nurture a conservative political philosophy, Marshall preserved its legacy through his jurisprudence. The values the chief justice defended on the bench were those of the Augustan Enlightenment: He believed in the supremacy of reason over passion, the general welfare over parties and factions, the national government over the states, and the wise, virtuous gentry over the mob. He admired George Washington, under whom he had served at Valley Forge, and made time between court terms to write a multivolume biography of his hero. Marshall felt a deep respect for the rights of property, having worked hard himself to become a man of substance; as late as 1829, he endorsed property qualifications for voting.

His friends among the Virginia gentry found Marshall a hearty companion, enthusiastic sportsman, and appreciative wine-drinker. Unlike his cousin Thomas Jefferson he showed no inclination toward science or philosophy; Marshall preferred lighter reading like Jane Austen novels. Between Jefferson and Marshall there existed a bitter personal enmity of long standing. Ironically, of the two, Marshall possessed more of the common touch.

73

The most important of Marshall’s personal qualities was the respect he commanded among his colleagues on the bench. In thirty-four years on the Supreme Court he almost always persuaded a majority to go along with his point of view. Although the justices spent much of the year “riding circuit” to try cases and hear appeals from federal district courts, when they were in Washington they all lived together in a single boardinghouse. (Their families, like those of congressmen, remained in their homes scattered about the country and did not set up residences in Washington.) In their boardinghouse the justices bonded closely together, which helps explain their tendency to decide cases unanimously. The chief justice approached the law with a practical rather than scholarly aim, relying upon his colleagues on the bench for supplementary learning. The associate justice who would prove Marshall’s most valuable coadjutor was the formidably learned Joseph Story of Massachusetts, who had joined the supreme bench in 1811. Appointed by Madison, young Story reflected the new views of the nationalist wing of the Republican Party.

74

Surprisingly enough, the major constitutional case confronting the Court in the winter of 1815–16 involved John Marshall not as chief justice but as an interested party in the suit. Back in 1793, Marshall, along with his brother and brother-in-law, had invested in 160,000 acres of land on the Northern Neck of Virginia. Their syndicate bought the land from the heir of Lord Fairfax, who had been one of the largest Loyalist landowners at the time of the Revolution. But the title conveyed to the Marshalls by their purchase was open to question. In 1779, the state of Virginia had laid claim to Fairfax’s land as part of a policy of confiscating the property of Loyalists. The Marshalls were relying on the 1783 peace treaty between Britain and the United States, which stipulated that confiscations from Loyalists would be restored and their property respected. However, state courts were notoriously unenthusiastic about enforcing the rights of Loyalists, and Virginia had subsequently conveyed some of the Fairfax land to other parties. Another complication was the fact that it was not clear whether Lord Fairfax’s will leaving the land to his nephew in England was valid under Virginia common law.

Jay’s treaty with Great Britain reaffirmed British and Loyalist property rights in 1795, strengthening the case for the Marshalls. But their local political position was weak, since Federalists had become almost as unpopular in most of Virginia as the Loyalists from whom their title to the land derived, and the landlords compounded their unpopularity by billing their tenants for quitrents, the feudal dues Lord Fairfax had collected in colonial times. In 1796, the state legislature enacted a compromise that divided the Fairfax lands between the Marshall syndicate and the commonwealth. But one legal issue was left unresolved: Had the state of Virginia the right to sell a parcel of the land to David Hunter long before the compromise had been enacted? Title to this part of the former Fairfax estate remained in litigation even after the legislative compromise.

75

In 1809, the Virginia Court of Appeals (state supreme court) found for Hunter, upholding the confiscation act of 1779 and invalidating the Marshalls’ title to the tract in question. The opinion was written by Spencer Roane, the leading judicial exponent of state rights, son-in-law of Patrick Henry, and the man Thomas Jefferson would have liked to appoint chief justice of the United States. Because rights involving a federal treaty had been called into question, the Marshalls were able to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Of course John Marshall recused (disqualified) himself from participating in the decision, and the opinion of the court was delivered in 1813 by Story. Story completely reversed Roane’s decision, declaring that the state confiscation had been invalidated by federal treaty, Fairfax’s will was valid under Virginia’s common law, and the Marshalls’ title to the disputed tract was confirmed.

76

The case took an even more surprising turn when the Virginia Court of Appeals refused to obey the decision of the United States Supreme Court. Spencer Roane claimed that final authority to define Virginia law had to rest with Virginia’s own highest court, and that the U.S. Supreme Court had no power to review its decisions. He called the Constitution of the United States a “compact” to which the states were parties and cited the favorite proof-text of Jeffersonian state-righters, Madison’s Virginia Resolutions of 1798. Roane went so far as to declare that section 25 of the United States Judiciary Act, authorizing appeals from the highest state courts to the U.S. Supreme Court, was unconstitutional! When John Marshall learned of this, he wrote out an appeal petition in his own hand and took it to Associate Justice Bushrod Washington (nephew of George) to endorse for hearing at the next term of the Supreme Court, just weeks away.

77

Since the Virginia court refused to forward the record of the case for review, files on it had to be hastily assembled. This time around, the case bore the name

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee

. (Martin was the person who had sold the land to the Marshalls and whose title they had to validate.)