What Hath God Wrought (16 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

The president’s resolution of the crisis was initially explained through the Washington

National Intelligencer

, journalistic voice of the administration. The Spanish authorities in Pensacola would be restored. In occupying the Spanish posts General Jackson had acted on his own responsibility, without orders, but out of patriotic motives and on the basis of reliable information. Meanwhile, Monroe wrote personally to Jackson, taking the same position and choosing his language with care. The limits imposed on Gaines had also been intended for Jackson, and he should have understood this, said the president: “In transcending the limit” of your orders, “you acted on your own responsibility.”

36

In the same letter (dated July 19), the president suggested to Jackson that the general might like to have his reports from Florida altered to make sure the written record backed up Washington’s interpretation of events, blaming everything on the Spanish authorities. He offered to have someone in Washington make the appropriate changes in the documents. Monroe was already worried about a congressional investigation. Jackson indignantly rejected the favor, for which historians can be grateful. He insisted that his orders had authorized him to do whatever was necessary to eliminate the Seminole threat and that he had nothing to hide or excuse.

37

Monroe’s suggestion to Jackson casts some doubt upon the integrity and completeness of the other documentary records relating to the subject. Might Monroe’s letter to Calhoun of January 30, 1818, have been a later interpolation? It could have been intended to legitimate the assurances Monroe had provided Congress on March 25, 1818, that “orders have been given to the general in command not to enter Florida unless it be in pursuit of the enemy, and in that case to respect the Spanish authority wherever it is maintained.”

38

Perhaps James Monroe’s soul had some speck on it that Jefferson did not know about.

When Congress assembled in December 1818, the pressure for inquiry and discussion of the Florida invasion proved irresistible. Interestingly, no one criticized the president; the controversy addressed Jackson’s conduct. Both houses took up the subject. The climax of the congressional debate occurred on January 20, 1819, when Henry Clay of Kentucky left the Speaker’s chair to address the House of Representatives. This was the first of the great speeches that would bring Clay renown. Having been announced in advance, it drew crowds to the galleries; the Senate adjourned so its members could attend too.

39

Clay began with expressions of personal respect toward President Monroe and General Jackson, then listed the four motions before the House. The first expressed “disapprobation” of the trial and execution of Ambrister and Arbuthnot; the second would require presidential approval for future executions of military prisoners. The third expressed “disapproval” of the seizure of the Spanish posts as a violation of orders and an unconstitutional waging of war without congressional authority. The last would forbid the U.S. military to enter foreign territory without prior Congressional authorization, unless in hot pursuit of an enemy. (The issues were, of course, not unlike those confronted in later attempts by Congress to exercise oversight of American foreign policy.)

The genesis of the war against the Seminoles, Clay declared, lay in the unjust Treaty of Fort Jackson, which created a resentful population of refugees in northern Florida. In actually initiating hostilities, the whites bore at least as much responsibility as the Indians. Nor had the war been prosecuted with honor: Hanging the two chiefs captured by deception was a regression to barbarism. Jackson should have considered himself bound by the orders to Gaines not to attack Spanish posts. The possible capture of the forts by the Seminoles, offered by Jackson as his excuse, was wildly improbable. As to the British prisoners, there was substantial doubt of the guilt of Arbuthnot if not Ambrister, and the proceedings against them were indefensible. They had been charged with newly invented crimes before a court whose jurisdiction was unknown to international law; their trials had been a mockery of due process and their executions carried out with unseemly haste.

40

Clay was still resentful that he had not been named secretary of state, but he had plenty of statesmanlike reasons as well as personal ones for finding that Jackson’s conduct set a dangerous precedent. “Beware how you give a fatal sanction, in this infant period of our republic, scarcely yet two score years old, to military insubordination. Remember that Greece had her Alexander, Rome her Caesar, England her Cromwell, France her Bonaparte, and that if we would escape the rock on which they split, we must avoid their errors.”

41

Despite Clay’s eloquence, however, after three weeks of congressional argument, all the motions critical of Jackson were defeated. (On the most important, the bill to prohibit American troops entering foreign territory without prior Congressional approval, the vote was 42 for, 112 against.)

42

Jackson’s confidant, John Rhea of Tennessee, summed up the attitude of the majority: “General Jackson was authorized by the supreme law of nature and nations, the law of self-defense,…to enter the Spanish territory of Florida in pursuit of, and to destroy, hostile, murdering savages, not bound by any obligation, who were without the practice of any moral principle reciprocally obligatory on nations.”

43

Jackson’s critics in the cabinet, their views not having prevailed with the president, supported the Monroe–Adams line in public, though their political followers were not so constrained.

Nor did the foreign powers induce the administration to censure the general. The Spanish had hoped that because of what happened to Ambrister and Arbuthnot, the British would make common cause with them in denouncing the Florida invasion, but this was not to be. Britain was already finding the postwar renewal of commerce with the United States extremely profitable. The trade that the British had carried on for so long with the Native Americans of the borderlands was now dwarfed by the cotton trade with their white enemies. The foreign secretary, Lord Castlereagh, decided not to let the fate of two Scotsmen in a remote jungle interfere with the conduct of high policy, which now dictated good relations with the United States and a severing of those ties with the Indian tribes that had been advantageous before and during the War of 1812. Ignoring the outrage voiced in the British and West Indian press at Jackson’s action, he calmly went ahead with implementing the Anglo-American Convention of 1818. Even the indignation of the Spanish cooled when the Americans restored to them Pensacola and St. Mark’s—but not, significantly, Fort Gadsden, the former Negro Fort, which remained under U.S. occupation.

44

Having arrived in Washington near the end of the congressional debate, Old Hickory felt he had been vindicated and was accorded the treatment of a national hero. More than any other one person, John Quincy Adams had saved him from the disavowal and censure of his civilian superiors, but it was a debt Jackson never acknowledged. Jackson seemed to remember grievances more than favors. He never forgave Henry Clay.

III

John Quincy Adams was a tough negotiator. This Yankee in an overwhelmingly southern administration determined to prove himself worthy of having been entrusted with the State Department. In November 1818, Secretary Adams composed a truculent memorandum, blaming everything in Florida on Spanish weakness and British meddling, while completely ignoring the gross American violations of international law. This he sent to the U.S. minister in Madrid, George Erving, with instructions to show it to the Spanish government. Pensacola and St. Mark’s would be returned this time; next time, Adams warned, the United States might not be so forgiving. Actually, the letter was intended at least as much for British and American consumption as for the Spaniards, in order to rebut the critics of Jackson and justify the course the secretary of state was pursuing. Adams saw that it reached all its intended audiences. Jefferson, reading it in his retirement, gave the statement his hearty endorsement.

45

The United States had been actively negotiating with Spain for the Floridas since before the War of 1812; their acquisition was a top priority within the Monroe administration. Spain at the time was locked in a gigantic and protracted struggle to retain her far-flung New World empire. Revolution had broken out in 1809–10 and spread through most of Latin America. This, Adams knew, was why Ferdinand VII’s government could not spare troops for service in Florida, either to control the Seminoles or to resist the United States. The administration did not wish to become involved in this Latin American war, though neither did it prevent some of its citizens from fitting out privateers to aid the revolutionaries and prey on Spanish shipping (as the Spanish government did not prevent the Seminoles from raiding across the border). Adams was not nearly as sympathetic toward the revolutionaries as Clay was; nevertheless, he intended that his own country should profit directly from the Latin American independence movements by seizing the opportunity they created to help dismember the empire of the

conquistadores

.

46

Jackson’s invasion of Florida temporarily hindered Adams’s negotiations because the Spanish minister, Onís, withdrew from Washington in protest and did not resume direct contact with Adams until October 1818, after the restoration of Spanish rule in Pensacola and St. Mark’s. In the meantime, however, Adams communicated with Onís through the French legation. But the lesson of Jackson’s invasion had not been lost on the authorities in Madrid, who instructed Onís that it was hopeless to try to retain Florida and to make the best bargain he could for it. The negotiations progressed feverishly throughout the fall and winter.

47

Adams’s ambitions were not confined to Florida. Spain had never recognized the legitimacy of the Louisiana Purchase, because in ceding Louisiana to France in 1800, the Spanish had stipulated that the province could not be transferred to any third power without their prior consent. Besides resolving this long-standing problem, Adams wanted to negotiate a treaty that would establish the boundaries between the United States and New Spain (Mexico) all the way to the Pacific in such a way as to strengthen the American claim to Oregon. Adams had a great interest in the trans-Pacific trade with China and had already been instrumental in recovering the Oregon fur-trading post of Astoria for the United States. At a critical juncture in the negotiations, therefore, Adams widened the scope of the discussions to include defining a boundary between Spanish California and the Oregon Country.

48

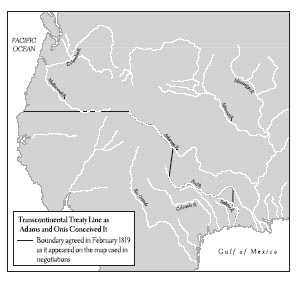

On February 22, 1819, George Washington’s Birthday, Adams realized his dream in one of the most momentous achievements in American diplomacy, the signing of the Transcontinental Treaty of Washington. By the terms there set out, Spain not only acquiesced in the earlier American occupations of chunks of West Florida but ceded all the rest of both Floridas to the United States. The Louisiana Purchase was acknowledged and its western boundary fixed along the Sabine, Red, and Arkansas Rivers, and then north to the 42nd parallel of latitude. Adams had stubbornly insisted on the west banks, not the centers, of these rivers as constituting the boundary, so as to monopolize them for American commerce. The 42nd parallel was identified as the limit of Alta California. North of that line Spain relinquished all of her claims in favor of the United States. Coming on top of the joint occupancy agreement recently concluded with Great Britain over Oregon, this Transcontinental Treaty constituted another big step toward making the United States a two-ocean power. (The maps consulted in the negotiations were inaccurate, so the lines that were drawn on them looked different from the way they would appear on a modern map.) At “near one in the morning,” Adams wrote in his monumental diary, “I closed the day with ejaculations of fervent gratitude to the Giver of all good…. The acknowledgement of a definite line of boundary to the South Sea forms a great epocha [

sic

] in our history.”

49

Of course, the United States had had to give up something in return for these huge concessions by Spain. The Spanish negotiator was nobody’s fool; considering the weakness of his position, Onís did not make a bad bargain for his king.

50

In the first place, the U.S. government agreed to pay off claims by private American citizens against the Spanish government, mainly arising out of events in the Napoleonic Wars, up to a limit of $5 million. More important, the United States relinquished the claim that what is now eastern Texas should have been included in the Louisiana Purchase. At the start, Adams had been demanding the Colorado River of Texas as the boundary, but over the course of the negotiations he had gradually retreated to the Sabine. In making this compromise the secretary had been encouraged by the president. Ever sensitive to American domestic politics, Monroe felt that the acquisition of Florida needed to be paired with gains in the Oregon Country, lest northern congressmen complain. Committed to the ideal of consensus, Monroe did not wish to expose the administration to accusations of sectional favoritism by refusing to make concessions over Texas for gains in the Pacific Northwest.

51